Key Findings

Satirical comedy is uniquely effective in its ability to bolster media development objectives. Through its ability to attract audiences and provide news commentary in an entertaining way, it can be used as an important tool to promote freedom of expression, foster accountability and transparency, counter disinformation, strengthen media literacy, and support more sustainable business models for media outlets. Donor funded satire news and current affairs programs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iraq, Kenya, North Macedonia, Nigeria, Serbia, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe demonstrate the format’s ability to advance these objectives, and make the case for greater integration of satire in international media assistance programs.

– By combining the core tenets of professional journalism with comedy, satire news offers a unique avenue for bolstering media literacy and creating demand for independent information.

– In restrictive media environments, satire news can often operate more freely than more traditional independent news outlets due to their overt comedic intent.

– Satire media offer a potential pathway to sustainability for media organizations due to the format’s broad appeal and potential to reach large audiences, including hard to reach news audiences.

Introduction

This just in: Satire is serious.

Laugh all you want—its purveyors definitely want you to. Despite its comedic nature, satire has emerged in the last decade as a preeminent tool in the media development toolbox. Satirists may have entered the satire game hoping to have a few laughs themselves, and for many of them, laughs come first. However, with the increasing proliferation of satire shows globally, and the format’s proven ability to attract audiences and deliver news and information to communities, even the most playful of satirists are now saying take us seriously. As the media development community continues to expand its mission to protect free expression, buttress democratic institutions, and encourage media literacy among ravenous media consumers, it should do just that.

Satirical comedy speaks truth to power. Be it a satirical TV show, radio program, social media post, website, or sassy interjection from a child to a parent, satire says I’m down here, and I have something to say about you up there. You, the one in charge, holding the reins. May I have your attention? And, when satire is delivered insightfully, incisively, accurately—and, yes, tastefully and palatably—people respond; they pay attention. Their curiosity is piqued.

As protected by—and an exemplar of—freedom of expression, satirical comedy announces itself proudly as both vital to democracy in a “free” state and the beneficiary and proponent of heavyweight human rights provisions. As a result, it is no surprise that organizations devoted to international media development—the sector of enhancing media as a force for democracy and development—are partnering with local media producers around the world to experiment with using satirical comedy to support democratic debate and foster media pluralism.

But what democratic good does it actually achieve? Beyond making basic information more accessible, with the promise of a zinger at the end, is it worth donor investment? Is it too risky in restricted media environments because of its tendency to focus on contentious political issues and to poke fun at political leaders? What can satire really do? Thus far, the answer to that question—what can satire do—has focused on the impact satire has on the individual within a democracy or a society. Social scientists have dug into the many micro-psychological steps our brains must take to process satire. They’ve helped reveal what it means to “get” a satirical joke and how that feeds into learning and participation. But the effects of satirical comedy do not stop there.

As the media development space continues to evolve and employ a greater range of media formats, examples of comedy are becoming increasingly common, but there is little evidence of the genre’s comprehensive impact across the development sector. Through an analysis of satirical comedy projects in several distinct countries and regions, this report considers the appropriate scope and potential effectiveness of satirical comedy in international media development. In short, this report draws lessons learned across several case studies and provides recommendations for how media development actors can use satirical comedy to advance their objectives and deepen their impacts.

The Satirist Profile

Satirists around the globe generally agree that satirical comedy is most effectively implemented by those steeped in the creative, performative industries, rather than by civil society activists or journalists. Satirical comedy is often performed by creative and politically savvy goofballs. Like any other discipline, it requires much practice to build up the muscles necessary to craft thought-provoking humor that lands a punchline. While efforts are underway to improve gender balance in the satire industry, it remains a highly male-dominated space.

No laughing matter: Defining “comedy” in media development

Vladimir Nabokov said “satire is a lesson, parody is a game.”1 While satire may appear to focus its efforts on just “having a laugh,” it actually strives for something much more serious. It seizes the opportunity, through humor, to take advantage of the space around the laugh, to offer a point, a lesson, a clarification, a teachable moment, an exasperated expression of a common cause. As such, satirical comedy can come in many forms, be it sketch, late night, cartoon, sitcom, reality, puppetry, animation, festival, or in one of its most prominent incarnations, a parody of a newscast—the original “fake news.”

All forms have their merits and often adapt to their platform depending on the financial, political, and technological limitations. As a result, satirical comedy reaches audiences through a variety of legacy and new media. But it can teach an audience no matter how it may reach an audience. This paper, then, broadly considers satirical comedy by its format, platform, and purpose.

The interplay between these three elements cannot be understated. They expand or narrow a program’s audience and voice. A show’s purpose informs its ideal platform; its platform might dictate its format, and so on. For instance, while comics in some countries may be able to satirize social issues with ease, satirizing politicians or political issues may be more difficult. For this reason, a satirical show that makes light of “safer” social issues may enjoy a generous production budget on a mainstream TV channel, whereas a show that satirizes political powers will be taped in a garage for YouTube. The satirical comedy that audiences see is as much a result of the producers’ elbow grease and audience demand as it is the country’s media history and media constraints. The impact of satirical comedy must be considered within these enabling conditions and constraints.

Some satirical comedy shows include segments full of banal jokes without, it might seem, all that much to contribute to democratic progress. To be sure—as one learns after a few hours behind the scenes of a comedy show—some jokes simply don’t land. However, despite such misses, most satire news and current affairs programs nonetheless promote democratic agendas. A college try is still a try. Rather than adopt a strict categorization, this report considers a broad interpretation of satirical comedy’s format, platform, and purpose within international media development. So long as the satire program employs comedy as a way to inform audiences and promote democratic values constructively through traditional or alternative media, it deserves attention. What’s more, answering questions such as “what is satire?” or “how can we define its impact?” is difficult given that satire is so dependent on its context. For lack of a better definition, this report interprets satire, as many others have, by considering four key elements: aggression, play, laughter, and judgment.2

Case Study: Njuz.net in Serbia

In 2011, a handful of budding satirists created the satire news website Njuz.net in Serbia. Much like The Onion, Njuz bases its satirical news stories on hot-button, local current events. After growing a loyal fan base and receiving critical acclaim, the writers teamed up with Zoran Kesić in 2013 to produce the hit satirical TV show 24 Minuta sa Zoranom Kesićem

When researching contemporary satirists around the world, it becomes clear that virtually every country and culture has a long tradition of comedy and satire. Satirists draw both on the local history of satire and also nod to popular international satirical comedies as inspiration and influence. Many cited The Daily Show with Jon Stewart as the reason they felt that, if they merely put in the effort, maybe they could do it too, as recalled by Viktor Markovic, a writer of Serbia’s 24 Minuta sa Zoranom Kesićem.

The style and structure of many techniques found in The Daily Show were easily adapted to the news styles and humor sensibilities in other countries since all countries have their version of “the news.”3The Daily Show presented an attractive low-cost, revenue-generating, and adaptable TV format because it mimicked low-cost and adaptable news and current affairs programs already in circulation. In the 2000s and 2010s, local formats emulating The Daily Show bubbled up across the globe. Perhaps the most noteworthy is Bassem Youssef’s news satire TV show Al-Bernameg in Egypt.

The Al-Bernameg example in Egypt sets the backdrop for understanding how popular satirical comedy formats began to surface around the world, including in restricted countries, and how their role as robust vehicles for freedom of expression garnered attention by the international development community. The introduction of satire in numerous contexts can similarly be traced to attempts to emulate formats from other countries. For instance, Britain’s popular satire puppet show Spitting Image, which first aired in the 1980s, inspired Les Guignols in France, and later the popular XYZ Show in Kenya.4 Though the original shows retain their intellectual property rights, they have not been franchised, which has allowed local adaptations to proliferate. As news satire scholars highlight, “part of the power of news parody seems to lie in its portability, its ability to cross national, cultural, and linguistic boundaries.”5 But “the news” is different in different countries, as are the historical traditions of comedy and satire, so these versions are necessarily different, unique in small but profound ways.

Despite the prevalence of such emulations, many satirical comedy formats are developed locally rather than adapted from previously popular global formats. The late Jaime Garzon, for instance, was a renowned Colombian political satirist in the 1990s whose popular shoe-shiner character Heriberto de la Calle provided critical news commentary through his witty chats with national personalities. His show was an isolated success, and media organizations and satirists in other countries did not readily adopt the format.

Sadly, Garzon was assassinated in 1999 in part due to his incisive satire, according to a Colombian court.6 Similarly, the rise and demise of Youssef’s show in Egypt, despite its gigantic success, illustrates how satire is always walking a political tightrope in countries with authoritarian governments or weak democratic institutions. These examples spook many media development actors from supporting satirists, and raise a number of critical questions: Will donors jeopardize their host-government relations by supporting a popular, critical TV show? Is it responsible to equip comics with a big microphone when they aren’t trained in law, human rights, or journalism? As one donor asked, “Is it safe to do this work? We don’t want to put anyone in harm’s way.”7 Fair questions. Satire packs a punch. It’s a high wire act.

Yet, despite these questions, satirical comedy persists and, in some contexts, thrives. It has prevailed and grown around the world through transnational media programming and increased support from the international development community. Despite a global downward trend of deteriorating freedoms of the press,8 satirical comedy offers a beacon, a glimmer of hope for alternative programming that holds the potential to catalyze wide-reaching pro-democracy effects.

Case Study: The Other News in Nigeria

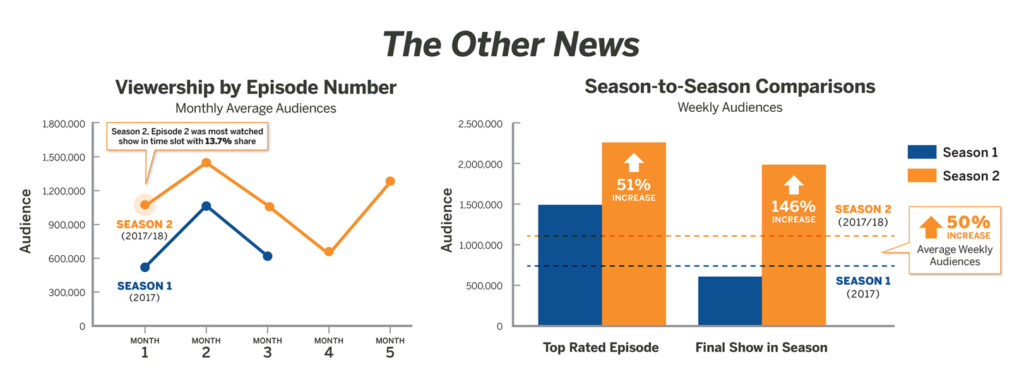

In 2017, Pilot Media Initiatives and Channels TV jointly launched The Other News—Nigeria’s landmark news and political satire TV show—with support from the Open Society Initiative for West Africa. In its first season, The Other News aired 12 weekly episodes from July to October 2017, and its viewership ballooned from 1 million on its pilot episode to a high of 1.7 million on its season finale. By mid-season, it was the most watched TV show in its time slot with 16 percent of the total audience share. As of April 2020, The Other News had broadcast over 70 episodes—60 of which were fully funded by local sponsors—and was in pre-production for its fifth season.

Why should media development actors employ comedy and who should they support?

A donor, an implementer, and a comic walk into a project…

At first blush, the development community’s motivations for supporting satirical comedy might seem straightforward: It is, after all, informative. But satire does more than wrap humor and entertainment around important information.

Individual Audience Effects

Social scientists have researched the ways satirical comedy informs, motivates, encourages, or discourages individuals. As one might expect, much depends on the joke and the context. Some studies suggest satirical comedy strikes a quick, efficient blow, resulting in changed attitudes and behavior—from punchline to belly laugh to a new view on the world—while other studies counter that satirical comedy merely reinforces predetermined worldviews and cultivates cynicism. To be sure, the authors have observed both dynamics. But what jokes do which and to whom? As the comedian might say in retelling a joke that relied so much on context—it was funny, trust me, you had to be there.

A substantial amount of peer-reviewed research identifies many positive outcomes associated with satirical comedy.9 Granted, the format, like all media, carries limitations and should not be put on a pedestal with the anticipation that it’ll rapidly inform, persuade, or mobilize audiences. A multitude of factors—some beyond the control of content creators—should manage expectations. But if satirical comedy programs apply the format—and yes, land their jokes—their audiences laugh while also increasing their likelihood of learning, seeking more information, thinking critically about news, and participating in issues raised on the programs.10

Despite the encouraging research on satire’s impact on the attitudes, beliefs, and level of political engagement of citizens, it poses limitations in terms of understanding audience effects in diverse contexts. The majority of research on satirical comedy focuses on the highly developed media ecosystem in the United States, where a growing multitude of satirical comedy programs compete against one another through hyper-segmented audience targeting. Unlike in Lagos, Skopje, Caracas, or Bishkek, where access to the genre is still limited, “yet another” show in New York may have a marginal impact.

Freedom of Expression, Accountability, and Transparency

Perhaps the most salient benefit of satirical comedy to media development objectives is its contribution to the promotion of freedom of expression via two paths: its content, and its existence. Satire holds the potential both to hold governments accountable through its content, and to serve as a vehicle for freedom of expression by the very existence of the programs themselves.

Just as it is vital for independent media to facilitate transparency and accountability as core tenets of democratic societies, so too is it vital for satirical comedies to skewer the powers that be and contribute to the fourth estate. Premised on actual news headlines, segments of the Iraqi news and political satire TV program Albasheer Show have held political and media powers to account in much the same manner as The Daily Show and independent journalists,11 for instance, by covering Iraqi government workings, or civil protests and the government’s response.12 In such cases, the show’s content fulfilled the same role as independent journalism, while standing as a beacon of freedom of expression.

Operating in a similar vein to traditional news, satirical comedy does sometimes perform news reporting or corruption commentary, albeit with a satirical twist. The Nigerian crew of The Other News, for instance, sometimes conducts unscripted interviews with real, newsworthy interviewees. The correspondent, rather than maintaining impartiality, adopts an absurdly biased position to turn the issue upside down. This demonstrates the genre’s ability to disseminate real news to audiences through entertainment, thereby providing the news media sector with a needed dose of innovation.

The fact that satirical comics sometimes face threats similar to those waged against journalists or civil society demonstrates their role in advancing freedom of expression, particularly in countries with weak democratic institutions and highly controlled media environments. The former producer of Albasheer Show, Hussam Hadi, faced threats, intimidation, and torture for his satirical comedy work with Albasheer Show before he was forced to flee Iraq.13 And in Serbia, the teams of the satirical and late-night comedy TV programs Kesic and Ivanovic received threats in April 2020 after making comments critical of the government.14

Satirical comedy can serve as a vehicle for freedom of expression by the presence of the program, which contributes to media pluralism and typically offers oppositional viewpoints. As Nkechi Nwabudike, the former head producer of Nigeria’s The Other News, said, the show’s mere existence “proved that you can get away with much more than you would expect in Nigeria. It’s built into our national psyche that the powers won’t take it. But there’s so much you can do in Nigeria these days where you can openly criticize the government.”15 The presence of popular and cutting satirical comedy programs thereby bolsters a country’s freedom of expression by adding an alternative and critical voice.

Case Study: Al-Bernameg in Egypt

Bassem Youssef, a cardiologist by trade, began posting homemade satire videos about the Arab Spring and Egypt’s corrupt political leaders in March 2011. His posts quickly tallied over five million views on YouTube, and he was offered a show deal later in the year with local private network ONTV. Al-Bernameg became one of the most watched shows in the region, with some episodes surpassing 40 million viewers throughout the Middle East. TIME magazine named Youssef one of the 100 most influential people in 2013, and he was often referred to as the “Jon Stewart of Egypt.” However, after Egyptian political powers turned against the show, Al-Bernameg switched broadcasters several times due to government intimidation and meddling in its editorial policy. The show was cancelled in 2014 after three seasons and Youssef eventually fled from Egypt to the United States.

New Audiences

One of satirical comedy’s assets is its ability to reach new audiences that otherwise might not tune into independent news, investigative journalism, or critical commentary. By and large, youth tend to find satirical comedy appealing, but if the comedic elements are broad enough, the genre has potential to reach even farther.

For instance, the Nigerian privately owned station Channels TV is one of the most watched and trusted stations in the country. It has generated a loyal, news-hungry audience that is typically above 40 years old. In 2017, Channels TV added The Other News to its programming schedule, in part to cultivate a younger audience. The show proved so popular among youth that Channels TV witnessed a new 18-to-35-year-old audience migration specifically for The Other News.16 Such audience migration movements support the argument that satirical comedy is attractive to audiences that don’t typically consume news. In watching satirical news comedy TV, they learn about critical issues and are more likely to seek more information on the topics covered in the show.17

If tailored in the correct fashion, satirical comedy can appeal to other difficult-to-reach audiences. In Venezuela, Plop Media created El Betulio, a show featuring the puppet character El Betulio—a middle-aged delivery driver—to better connect with rural audiences. El Betulio uses satirical comedy to explain complex issues about public services, health, and transportation in contexts more relatable to rural communities. Employing offline and online platforms, the show is distributed through mediums accessible to its target audience, such as YouTube, print, and community screenings.18

Case Study – Plop Media in Venezuela

In Venezuela, Plop Media, which began with the satirical news website El Chiguire Bipolar in 2008, has since launched satirical news TV shows, sitcom animations, a comic travel/food series, a satire puppet show, and an investigative journalism/animated comedy series.19 It develops multiplatform content with private sector clients and international development partners.

Media Literacy, Countering Disinformation

Media literacy is increasingly recognized as an important facet of countering misinformation and disinformation in emerging democracies. Real and fabricated news stories compete in an interconnected multimedia system for attention, likes, and reposts.

Such an environment is ripe for the spread of misinformation, and media literacy activities that strengthen the public’s ability to access, analyze, and critically evaluate news media are one tool to help curb it. As noted above, satirical news comedy can serve as a gateway to more information about issues covered in the program.20 In this respect, satirical comedy acts as both a watchdog and an educator, helping audiences think critically about the media they consume and begin to recognize misinformation.21 Because the genre frequently plays on the typical “news” formula and the news-making machinery of both authentic and false news, it can enhance audiences’ ability to analyze and engage with media in their daily lives. As one researcher wrote, “The Daily Show is simultaneously an alternative source of news, a form of media criticism, and a populist ‘module’ on media literacy that promotes a modernist perspective on media awareness to a young audience that does not yet have a fixed relationship with journalism.”22

In some cases, this also means calling out biased, low-quality, or generally absurd statements already circulating in local news coverage. For instance, after local journalists and politicians used jungle wildlife analogies to explain political developments, The Other News heightened the absurd and reported from the jungle itself. Through the lens of humor, the segment exposed the artificial terminology of political theaters, and sometimes of news media themselves. Similarly, North Macedonia’s Fcerasni Novosti (Yesterday’s News) reframes biased, absurd, or hypocritical news coverage, all delivered through flawed news characters such as the anchors and field reporters, to expose the machinery of the captured local media. Yesterday’s News presents as much a different point of view of current affairs as it does a lesson in how the news is made.

With some forms of satirical comedy so closely resembling actual news, satirists have had to exercise responsibility in clearly declaring their content as entertainment, not to be confused with traditional news. The Other News team faced this dilemma when premiering the show on Channels TV, a 24-hour news network. The team recognized the need to signal to audiences that, despite airing on a mainstream news channel, The Other News was a deliberate departure into comedy. To address this, the show began with a cold open segment that ran voice over of a real news headline over absurdly exaggerated video footage of what one could interpret only as a clear joke. Such declarative signaling in format design ensures audiences’ expectations are met, and confusion about the program’s intent as satire or traditional news is avoided.

Youth Engagement and Voter Education

Youth aged 18 to 35 are often a coveted and difficult political audience to reach in many countries,23 especially when it comes to “dry” topics like voter engagement or corruption. One of the superpowers of satirical comedy is its broad appeal to disaffected youth audiences. Projects that have taken the form of news satire, scripted comedy, or a satire news website have often secured loyal youth fan bases.

For instance, in Venezuela, Plop Media has entertained and informed young Venezuelans through its news and political satire show Pero Tenemos Patria. The weekly YouTube series indirectly encourages young voter turnout and participation in public policy. As Plop Media CEO Juan Ravell said, “we kept hearing that to better understand the jokes in Pero Tenemos Patria, fans were reading other news sources to learn about the topic.”24 And in North Macedonia, one participant of a focus group study of Yesterday’s News said, “I was 18 last year. No peers of mine watch the news. Everybody watches Yesterday’s News. This type of show attracts most youth viewers.”25

Once satirical comedy has hooked youth audiences, what comes next? Studies have shown its unique elements of positivity, such as hope and joy, connect with viewers’ emotions and empower them to take action on the issues covered in the satire.26 Satirical comedy, therefore, can serve as a dynamic mechanism for reaching youth, lifting them out of disaffection and prompting them to take action on important political and social issues. As one participant of the research on XYZ Show stated, “I’ve made some progress after watching XYZ. I’m now 19 and I’ll be voting for the first time. Politicians will not buy me with money. I’ll choose a leader based on integrity and track record.”27

The news and political satire TV shows Zambezi News and The Week, produced in Zimbabwe by Magamba Network, have regularly included calls-to-action in their episodes to engage youth on activist issues. Engagement topics in the past have encouraged young audiences to voice their opinions to parliamentarians, register to vote, and facilitate hashtag campaigns on Twitter.28 Similarly, The Other News sparked a trending hashtag on Twitter (#RochasHowMuch) with its call for greater government transparency on alleged abuse of public spending.29

Furthermore, research from the United States demonstrates that “watching political comedy shows may be associated with greater knowledge about primary campaigns among certain subgroups of audience members.”30 As presidential candidates campaigned before Nigeria’s 2019 election, The Other News, with its loyal youth audience, was able to closely follow the run-up to the election in its weekly broadcasts. Though not conceived as an election program, The Other News nonetheless educated voters, and young voters in particular, about the upcoming election.

Case Study: XYZ Show in Kenya

Buni Media first launched the critically acclaimed XYZ Show, a puppet satire TV show on Citizen TV, in 2009. XYZ Show was designed as a creative tool for awakening public interest and engagement in contemporary issues facing Kenya and African societies around the world. Since then, Buni Media has produced a satire festival, workshops, and other entertaining and informative content.

Comedy’s unique and long-lasting impact on media ecosystems

Sustainability in Open, Restricted, and Closed Environments

Project sustainability is an oft-cited challenge in the international media development community.31 Many media projects have effectively promoted democratic principles, and yet often the content comes to an end when donor funding dries up. Developing satirical content that operates within the parameters of the media environment and meets the demands and preferences of local audiences could be crucial in nudging a project closer to its sustainability potential. Satirical comedy, with the appropriate format and distribution package, can become popular to highly coveted youth audiences, therefore holding greater potential to attract advertising and become sustainable in local markets.

The international development community and advertisers, sponsors, and distributors often have an overlapping interest in reaching youth aged 18 to 35. What’s more, in many countries where the international development community operates, there is an overwhelmingly large youth population.32 This shared interest of the public and private sectors to reach the same audience creates an opportunity for project sustainability.

More broadly, in many countries with restrictive media environments, the purveyors of satire news must tread carefully to maintain their independence and stay on air. In some cases, distributors and advertisers support a show only if they are able to exercise some degree of editorial influence. In others, media outlets and advertisers refuse to touch a satirical comedy show due to fear of government restrictions over content. Further, given that in many contexts the owners of distribution channels and advertising agencies are often political moguls or those with close ties to political powers, some projects are prevented from seriously materializing altogether. The examples below illustrate how, despite the odds, some satirical comedy shows prevail, even in environments with restricted and closed media ecosystems.

For instance, The Other News in Nigeria was designed to transition from international development funding after season one to commercial funding for follow-on seasons. Local commercial sponsors were interested in picking up the program because of its popularity. While many media projects struggle to survive once donor funding comes to an end, The Other News became the most watched TV show in its prime-time slot during its first season. This, coupled with the high production quality and tasteful content, encouraged advertisers and sponsors to back the program. The Other News case study demonstrates how a satirical news program supported by international donors became locally sustainable through informative and entertaining content that attracted audiences.

Wary of Nigeria’s sometimes restrictive media environment,33 implementers were initially uncertain that a program like The Other News could be viable. Despite this uncertainty, all key partners agreed to move forward with the project because of their commitment to the show’s cause.

In other more restrictive media environments, satirical comedy has still managed to carve out a variety of sustainable business models. The creators of Njuz.net never thought they would be able to earn a living writing satire, but advertising revenue began trickling in once the website established a solid following, and the writers continued to generate income with the satire TV show 24 Minuta sa Zoranom Kesićem. Despite Serbia’s ranking as a “partly free” country by Freedom House,34 not only did the satirical comedy activities blossom from a website to a full-fledged TV show, but both platforms have generated commercial revenues that have allowed the programs to continue for years.35

In Zimbabwe, government restrictions limited distribution and sponsorship opportunities of Magamba TV’s weekly political satire show, but the team uploaded videos online and handed out DVDs to local communities. After a few steady seasons of high-quality content, satellite TV channel Zambezi Magic—a channel on the Africa-wide DSTV satellite network—approached the creators to fund and broadcast several seasons of Zambezi News. Alongside the commissioning of the satirical comedy TV show, Magamba TV’s parent organization, Magamba Network, branched out to launch other satire TV shows, audio platforms, open citizen engagement tech applications, culture festivals, and a creative entrepreneur hub, as well as their professional media production services.36 As diverse as these initiatives are, they maintain a common thread of youth-driven engagement. The approach informs and engages youth through satirical comedy, entertainment, and competitive multiplatform activities with a mix of public and private sector funding. The complementary projects allow for cross-promotion of youth activist projects overseen by Magamba Network, while diversifying the organization’s income streams.

A similar expansion of satirical comedy brands through multimedia networks can be found in Kenya. After producing the XYZ Show, Buni Media implemented the Africa Satire Festival, an illustration project of Kenya’s constitution, puppetry for activism workshops, a documentary series for Kenyan TV, and a spin-off satire puppet show in Nigeria called Ogas at the Top.37

In North Macedonia, the producers of Yesterday’s News (Good Mood Media) have managed to continue airing the show for over five years in a restricted and small media market serving a national population of two million. Though much of the show’s funding is derived from the international development community, the creators offer their talented storytelling skills through professional media services to generate additional revenue. Going forward, the group has an eye on opportunities to produce regional content: “the Macedonian market is too small, but we see promise in pan-Balkan content,”38 said Vladimir Ognjanovski of Good Mood Media.

In Venezuela, Plop Media’s satirical comedy programming was funded by both commercial partners and international development donors, depending on the project and amount of political space available in Venezuela at a particular time. Despite what is now a highly restrictive environment for free expression,39 the outlet remains financially stable, even as it faces a quasi-exile media situation in which some staff operate inside Venezuela and others outside. Similar to Good Mood Media in North Macedonia, Plop Media has circumvented restrictions in-country by producing more regionally appealing content.

Upon fleeing Iraq, the co-founder of the Albasheer Show began creating Puppets Republic—a political satire puppet show, produced by Horizon Light Media, in a format that could logistically operate from outside Iraq. With a cast of puppets that look strikingly similar to their political inspirations, the show was pulled from the Iraqi satellite channel Alsharqiya TV for refusing to censor content critical of political powers. The show moved online and uses Facebook and other social media platforms to penetrate Iraqi audiences.40 The series attracted over 400,000 Facebook followers in the first three months. Despite the highly restrictive media environment in Iraq, the satirical content persists by using an exile media approach.

Through the course of expanding their satire and creative portfolios, Magamba TV, Good Mood Media, Buni Media, Plop Media, and Horizon Light Media have offered professional media production services to public and private sector clients, expanding their sources of revenue. Support from the international development community, through a patchwork of complementary projects, gradually helped the organizations build more dynamic small businesses that have proven effective in disseminating critical content and holding political powers to account. The above examples illustrate how satirical comedy projects have sustained themselves in relatively open, restrictive, and even closed media environments. The unique ability of satire to sustain itself derives from its ability to reach diverse audiences, including youth and regional audiences, which is of value to a wide variety of supporters and advertisers.

Case Study: Yesterday’s News in North Macedonia

In North Macedonia, the production company Good Mood Media satirizes local news and current affairs issues through its weekly TV show Fcerasni Novosti (Yesterday’s News). Premiered in 2016, the show has satirized news through parody for over 150 episodes broadcast on local TV and popular online platforms.

Ripple Effects in Media Landscapes

Satirical comedy programs impact surrounding media ecosystems—nationally and internationally—in a number of unexpected ways. In lucrative media markets, there are numerous attempts to create spin-offs or copy-cat satirical comedy programs. And in more restrictive markets, the production companies and outlets behind satirical programming have developed more dynamic business models. The knock-on effects from satire projects can therefore be felt at the level of individual media organizations and within media markets more broadly.

There are a number of examples of satirical comedy programs inspiring similar programs, both within the same country and in other countries. After the success of the puppet satire XYZ Show in Kenya, the creators traveled to Nigeria to replicate and scale the format in Africa’s largest country. Buni Media launched Nigerian series Ogas at the Top in 2014. The show enjoyed mixed degrees of success, but one of the team’s writers later went on to become head writer of The Other News.

Similarly, former staff at Plop Media’s El Chiguire Bipolar website continued their satirical comedy work as writers, producers, or stand-up comics for local production companies and HBO’s Mexican satirical news TV show Chumel con Chumel Torres.41 Comedy projects provide opportunities for budding satirists to enhance their political acumen and strengthen their joke-writing skills, cultivating a more professional satire workforce.

After The Other News became a hit in Nigeria, competitor channels apparently reached out to team members of The Other News in an effort to produce another news and political satire TV show.42 However, to date, no other prime-time mainstream TV show has emerged in the Nigerian media landscape. The expression of interest from other channels to add new formats to their programming portfolios demonstrates a local media landscape adjustment.

There are also several examples that demonstrate how satirical comedy has inspired other media organizations to develop more resilient business models. Independent media in restricted, and even open, countries have struggled to identify a sound business model that facilitates financial independence and stability. While independent journalists and satirical comedians strive toward the same goal, because of the unique in-demand skills associated with satirical comedy, there are alternative revenue-generating activities available.

As discussed above, several satirical comedy teams have branched out to other types of comedy, media, and culture activities that aim to inform and engage audiences, particularly youth, on important issues. In doing so, the teams have generated revenue from public and private sector partners and strengthened their business practices. And, to reiterate, nearly all the mentioned satirical comedy teams offer professional services for public/private client contract work.

Admittedly, there are still many open market limitations in such contexts and, in the absence of commercial revenues, international development donors often step in to help keep local satirists afloat. But media development activities that foster more audience-led, competitive content creation that attracts private sector funds from broadcasters or advertisers nonetheless contribute to better business practices in local media ecosystems.

Case Study: Magamba TV in Zimbabwe

After piloting satirical news show Zambezi News in 2011, Magamba TV’s productions have expanded to include new shows distributed on satellite TV channels and online, as well as other youth-engagement projects such as the establishment of a creative hub and entertainment festivals. Today, Magamba Network is one of Zimbabwe’s leading creative production entities blending arts, digital media, activism, and innovation.

It’s funny ‘cause it’s true: How comedy leverages traditional media development

Leveraging Development Programming

Interviews with several satirical comedy teams reveal a common practice of using satirical programming to augment other development priorities. As CEO of Plop Media Juan Ravell said, “Satire is a shield that allows you to get away with more. The human rights angle is also a shield that allows you to say certain things; satire is a different and complementary shield.”43 In some cases, satirical comedy projects were linked by development donors to other initiatives; other times, satirical comedy unintentionally found its own way to development projects.

For instance, the creators of the satirical news website Njuz.org in Serbia organized road shows to rural communities to screen an entertaining satirical video about local governance and democracy issues followed by a question and answer session. Because of their work in satire and comedy, the Njuz team are local celebrities, so this encouraged a much larger turnout than similar events typically see. To capitalize on the popularity and high level of trust the public has in the satirists, Njuz also coordinated discussion topics with local civil society organizations (CSOs), resulting in an unexpected collaboration of traditional civil society and satirical comedians, which expanded the work of local CSOs to larger communities and enhanced public engagement.44

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, after producing satire puppet show Hyde a Park to highlight the positive work done by civil society organizations, creators pivoted their attention to more specific local election issues, providing an alternative platform for voter education ahead of elections.45

Another powerful example comes from Plop Media, which has combined the forces of investigative journalism with the broad audience reach offered by satirical comedy. In partnership with investigative journalists from IDL Reporters in Peru, Plop Media told the story of a prominent money laundering scandal in Latin America through a three-part animated web series. The satirists used factual investigative journalism combined with comedy to detail the high-profile scandal known as Lava Jato. According to the CEO of Plop, Juan Ravell, “The project expanded the reach of the excellent investigative work carried out by the journalists.” He further highlighted the power of comedy to influence audience perceptions and opinions by communicating messages in novel ways. “Comedy not only reaches more people, but it disarms audiences so they receive the message and information in a way straight journalism can’t deliver.”46

Do No Harm and Satirical Comedy

The media development community is rightfully wary of supporting projects that will cause harm to local satirists and others involved. Ultimately, there is no water-tight criteria to assess the risks as each context and country is unique. That said, ensuring satirical comedy satirizes across the political spectrum and delivers its content in good taste goes a long way in allaying concerns. Just as the interviews for this report identified a recurring concern of donors to ensure do-no-harm principles are upheld, most satirists reiterated the sentiment that they had faced less intimidation than expected.

As Nkechi Nwabudike, the former head producer of The Other News, said, “Nobody from The Other News was arrested or kidnapped. We didn’t even receive a letter of complaint. One time we received a phone call but that was it.”47 In essence, Nigeria’s media landscape experienced a little more freedom of expression wiggle room after The Other News was televised. Similarly, Farai Monro, the co-founder of Magamba Network in Zimbabwe, said, “Don’t get me wrong, we have faced attempts to raid our offices, ban festival activities, arrest our producer, and even demolish our creative hub. But in the context of Zimbabwe, we have not faced the type of intense, sustained intimidation you might expect.”48 Overall, they have been able to operate within the ongoing constraints in Zimbabwe.

Because satirical comics and journalists serve a similar role as alternative news outlets in ensuring media pluralism and holding governments to account, international donors should assess the risk to satirists according to the same terms as other independent media organizations. As more countries invoke, and potentially exploit, emergency measures to address the COVID-19 pandemic,49 the importance of holding truth to power and protecting freedom of expression is particularly urgent in 2020.

Case Study: Puppets Republic in Iraq

Puppets Republic is an Iraqi political satire puppet series produced in exile that has been distributed to Iraqi audiences via social media. The show bases its puppets on actual political and media figureheads in Iraq and the Middle East. The creator, one of the original founders of the hit Iraqi news and political satire show Albasheer Show, began Puppets Republic after emigrating to the United States.

Conclusions and Recommendations

It may not come naturally to them—their impulse, after all, is to make fun of themselves and the world around them—but satirical comedians are now asking of the development community: Please, take us seriously. And for good reason. Their work is compelling and gets results. The youth demographic, often difficult to reach and engage, is a fan, and often considers few sources more credible—in some instances, no one more trustworthy—than satirists. Viewers of satirical comedy learn, collect more information, think critically, and take action on important social and political issues. Satirical comedy embodies the core principles of freedom of expression, reaches beyond the choir, and fosters savvier media consumption habits. Satire teams implement an array of interconnected pro-democracy projects that offer dynamic sustainability models, and amplify other development programs. The ripple effects of satirical comedic programming are felt in their local media ecosystems, and beyond. This study of satire as a tool of media development provides a number of recommendations to enhance the use of satirical comedy in international media assistance programs.

- Think Big. Because satirical comedy teams often generate a variety of multimedia pro-democracy and youth engagement initiatives, donors and partners should consider the broad goals that satire media can address. There is a pattern of satirists accomplishing development objectives through TV, websites, campaigns, and festivals, and numerous formats, including puppetry, television shows, and traveling radio shows.

- Sustainability. Unique sustainability potential lies in satirical comedy because of its broad appeal and potential to engage new audiences that traditional news media often struggle to reach.

- Diversity. There is room for improvement in promoting diversity in satirical comedy teams, with women currently vastly underrepresented in the genre. While there were indeed several examples where women hosted shows (Yesterday’s News), managed the overall production (The Other News), or produced a series specifically targeting young women (Askana of Magamba TV), efforts should be made for greater gender balance and representation.

- Risk Analysis. When donors consider providing support to satirical comedy projects, they should align their risk analysis with that applied to independent journalists and civil society advocates. Similarly, freedom of expression legal aid support should be similarly provided.

- More Research. More comparative research on the democratic effectiveness of satirical comedy in various countries is required, particularly surrounding election periods.

All told, satire can clearly complement the news, increase citizen engagement and participation in political issues, and hold governments to account by offering a critical analysis of current events. International donor support should consider including satirical comedy within traditional media development programming. Those donors who see the potential in satirical comedy as part of an arsenal of tools to promote their pro-democratic aims—that the front lines should include a few punchlines—will get the last laugh.

Footnotes

- V.V. Nabokov, Strong Opinions (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973).

- G.A. Test, Satire: Spirit and Art (Tampa: University of South Florida Press, 1991).

- M. Garber, “Shocker of the Day: Stewart (Still) Most Trusted Newscaster in America,” Columbia Journalism Review, July 23, 2009, https://archives.cjr.org/the_kicker/shocker_of_the_day_stewart_sti.php.

- M. Onyiego, “Puppets, Political Satire Popular on Kenyan TV,” Voice of America, October 13, 2010, https://www.voanews.com/africa/puppets-political-satire-popular-kenyan-tv.

- G. Baum and J.P. Jones, “News Parody in Global Perspective: Politics, Power, and Resistance,” Popular Communication 10: 2–13, February 2012.

- A. Alsema, “Top Court Says State Responsible for 1999 Killing of Popular Colombian Satirist,” Colombia Reports, September 15, 2016, https://colombiareports.com/top-court-says-state-responsible-1999-killing-top-colombia-satirist/.

- Freedom House, “Democracy in Retreat,” 2019, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/democracy-retreat.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with the National Endowment for Democracy, April 2020.

- For more information, read J.P. Jones, Entertaining Politics: Satiric Television and Political Engagement (Plymouth, United Kingdom: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2nd Edition, 2010); A. Amarasingam, Stewart/Colbert Effect: Essays on the Real Impacts of Fake News (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2011); S.A. McClennan and R.M. Maisel, Is Satire Saving Our Nation? Mockery and American Politics (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014).

- A.B. Becker, “Political Satire Makes Young People More Likely to Participate in Politics. Trevor Noah’s ‘The Daily Show’ Is Likely to Continue That Trend,” London School of Economics, 2015, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2015/04/03/political-satire-makes-young-people-more-likely-to-participate-in-politics-trevor-noahs-the-daily-show-is-likely-to-continue-that-trend/.

- R. Thompson, “Meet the Iraqi Jon Stewart Who Ridicules the Islamic State for a Living,” VICE, May 5, 2015, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/znge88/ahmad-al-basheer-iraqs-jon-stewart-350.

- T. Rosenburg, “‘You Are Killing Us? We Will Make You a Joke.’ Meeting Ahmed Albasheer,” New York Times, December 26, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/26/opinion/albasheer-show-iraq-political-revolution.html.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Hussam Hadi, April 2020.

- OSCE Official Condemns Threats against Talk Show Authors in Serbia,” N1, April 21, 2020, http://ba.n1info.com/English/NEWS/a426909/OSCE-official-condemns-threats-against-talk-show-authors-in-Serbia.html.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Nkechi Nwabudike, April 2020.

- A. Chen, “Using Comedy to Strengthen Nigeria’s Democracy,” The New Yorker, January 22, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/22/using-comedy-to-strengthen-nigerias-democracy.; Nigeria’s News Satire Show ‘The Other News’ Hits Audiences of 2 Million and Brings in New Types of Viewers for Channels TV,” Balancing Act, July 13, 2018, https://www.balancingact-africa.com/news/broadcast-en/43623/nigerias-news-satire-show-the-other-news-hits-audiences-of-2-million-and-brings-in-new-types-of-viewers-for-channels-tv.

- C.B. Chattoo, Laughing Matters: Samantha Bee, Comedy and the Refugee Crisis, Center for Media and Social Impact, School of Communication, American University, May 2017, https://cmsimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/LaughingMatters-May2017.pdf.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Plop CEO, April 2020

- Plop Media website, accessed on April 23, 2020, http://plopmediacontent.com/.

- M.A. Xenos and A.B. Becker, “Moments of Zen: Effects of ‘The Daily Show’ on Information Seeking and Political Learning,” Political Communication 26, no. 3: 317–332, 2009.

- C. Peters, “‘Even Better than Being Informed’ Satirical News and Media Literacy,” in C. Peters and M. Broersma (Eds.), Rethinking Journalism: Trust and Participation in a Transformed News Landscape (Routledge, 2013), 171–88, https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/219032926/Rethinking_Peters_Chapter_12_submitted_proof_libre_1.pdf.

- Ibid.

- N. Zohdy, Examining Why and How to Engage Young People in Global Development: A Literature Review, Youth Power, World Bank, June 2017, https://www.youthpower.org/sites/default/files/YouthPower/files/resources/Examining%20Why%20and%20How%20Engage%20Young%20People.pdf.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Plop Media, April 2020.

- “Assessing Citizen’s Knowledge on Anti-corruption Issues (Yesterday’s News), Indago, June 2020.

- Chattoo, “Laughing Matters.”

- “XYZ Show Impact Report,” Infotrak Research and Consulting, September 11, 2012.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Magamba Network, April 2020.

- C. Ellah, “Twitter User Says Okorocha Is Donald Trump of Nigeria,” Lincornellah, December 8, 2017, https://lincornellah.com.ng/2017/12/08/rochas-okorocha-donald-trump-nigeria/.

- X. Cao, “Political Comedy Shows and Knowledge about Primary Campaigns: The Moderating Effects of Age and Education,” Mass Communication & Society 11: 43–61, 2008.

- M. Nelson and T. Susman-Peña, Rethinking Media Development: A Report on the Media Map Project, Internews, Media Map, World Bank, 2012, https://internews.org/sites/default/files/resources/Internews_1-9_Rethinking_Media_Dev-2014-01.pdf.

- J.Y. Lin, “Youth Bulge: A Demographic Dividend or a Demographic Bomb in Developing Countries?” World Bank Blogs, January 5, 2012, https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/youth-bulge-a-demographic-dividend-or-a-demographic-bomb-in-developing-countries#:~:text=The%20youth%20bulge%20is%20a,have%20a%20high%20fertility%20rate.

- “Nigeria: Climate of Permanent Violence,” Reporters Without Borders, 2020, https://rsf.org/en/nigeria.

- “Global Freedom Scores,” Freedom House, 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Njuz.net, April 2020.

- Magamba TV website, Magamba TV, accessed on April 22, 2020, http://magambanetwork.com/projects/.

- Buni Media website, accessed on April 23, 2020, https://bunimedia.com/.

- “Venezuela: Ever More Authoritarian,” Reporters Without Borders, 2020, https://rsf.org/en/venezuela.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Good Mood Media, April 2020.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Hussam Hadi, April 2020.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Plop Media, April 2020.

- Chen, “Using Comedy to Strengthen Nigeria’s Democracy.”

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Plop Media, April 2020.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with the National Endowment for Democracy, April 2020.

- Based on Pilot Media Initiatives interviews with the National Endowment for Democracy and Hyde a Park, April 2020.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Plop Media, April 2020.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Nkechi Nwabudike, April 2020.

- Based on a Pilot Media Initiatives interview with Magamba Network, April 2020.

- “Coronavirus: Impacts on Freedom of Expression,” Article 19, 2020, https://www.article19.org/coronavirus-impacts-on-freedom-of-expression/.