Key Findings

With independent media around the world in crisis, what is the role of international donors and private foundations? And how can these international actors provide effective support when the driving forces behind independent media’s decline—simultaneously technological, financial, social, political, and institutional—are so complex and difficult to disentangle?

This report argues that complexity is no excuse for inaction. Solutions to this crisis will require that political agency rise to the daunting level of the challenge, and that the structures of international cooperation—forged as the global response to World War II—are now put into motion to safeguard the foundations of independent media. Based on input from media actors, freedom of expression activists, implementers, and donors, the report puts forward three interrelated objectives that, if achieved, would help to international cooperation in the media sector.

1. Build the high-level political will and donor capacity needed to increase support to the media sector

2. Strengthen approaches to international cooperation focused on the development of media sector institutions

3. Enhance the effectiveness of media sector support by making it more demand-driven and coordinated

A Global Response to Independent Media’s Decline

Independent journalism, the kind that puts public interest above the interests of media owners or political masters, is now on the wane, ending a historic two‑decade expansion. The global turning point occurred around 2013, according to the University of Gothenburg’s “Varieties of Democracy” dataset.1 While other indices may differ slightly on the year the downtrend began, multiple sources corroborate that a steady decline in the freedom, capacity, and influence of the independent press has been occurring for well over a decade.2

Independent journalism, the kind that puts public interest above the interests of media owners or political masters, is now on the wane, ending a historic two‑decade expansion. The global turning point occurred around 2013, according to the University of Gothenburg’s “Varieties of Democracy” dataset.1 While other indices may differ slightly on the year the downtrend began, multiple sources corroborate that a steady decline in the freedom, capacity, and influence of the independent press has been occurring for well over a decade.2

With the crisis confronting independent media now so undeniable, why has the international community not yet formulated a stronger response? International assistance to the media remains a small fraction of a percent of total aid: just 0.3 percent of total official development assistance on average in recent years.3 No global fund, no grand partnership, no major new initiative has been unveiled for independent media.

This report describes how that may soon change as international donors devise ways to provide greater support to the media sector. Numerous obstacles stand in the way of greater international assistance being directed to the media sector. One surmountable, yet significant, impediment has been a genuine lack of understanding among donors about how to help. This is because the driving forces behind independent media’s decline—which are technological, financial, social, political, and institutional—are difficult to disentangle. The crisis in independent media and journalism is also intertwined with other global issues, such as a growing “information disorder,” and explicit efforts by authoritarian states and other nefarious actors to exacerbate and take advantage of this disorder.4

Fortunately, the international community is waking up to its responsibility to the independent media sector and has begun to figure out how to help. At a 2019 meeting entitled “Confronting the Crisis in Independent Media,” held at the headquarters of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, representatives of foreign ministries, official donors, private philanthropies, and major media development organizations shared ideas on how to confront the crisis and sketched out the elements of a more coordinated and effective global response. The recommendations emanating from that meeting (further elaborated in the conclusions of this report) took aim at three interrelated objectives.

- Build the high-level political will and donor capacity needed to increase support to the media sector. The meeting was the first since 2012 to bring together actors working to bolster high-level political will on media-related issues and those working on project design and implementation in the sector; both groups recognized the potential to work together. In particular, those actors working at the political level vowed to make use of the expertise, evidence, and networks possessed by others in the room as they build the case for more significant global action. Participants working on project design and implementation are considering options for new action as if political leaders call for a more vigorous response to the media crisis.

- Strengthen approaches to international cooperation focused on the development of media sector institutions. Journalists and publishers alone cannot save journalism. Confronting the media crisis will require institutions that can fairly and effectively govern and regulate media, including media councils, telecommunications and spectrum regulators, anti-monopoly authorities, self-regulatory bodies, journalist associations, press freedom advocates, blogger associations, universities and training/certifying bodies, and other institutions. Multi-stakeholder coalitions are also emerging as a promising way to build strategies for survival. With diverse members brought together by a shared interest in protecting the information space, these coalitions can work across borders and institutional barriers, and at multiple levels from the local to the global.

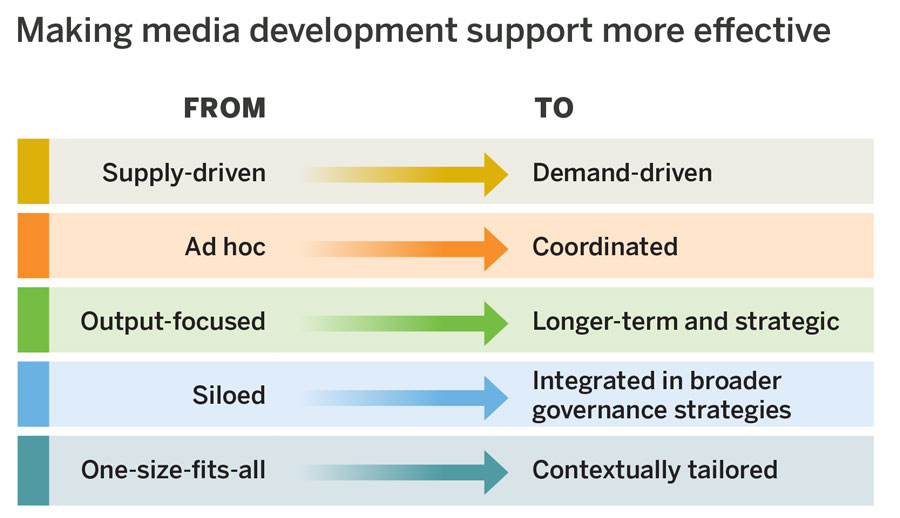

- Enhance the effectiveness of media sector support by making it more demand-driven and coordinated. Participants all agreed on the need to bolster the effectiveness of international cooperation in the media sector, emphasizing the importance of providing support that is demand-driven, coordinated, contextually tailored, and oriented toward long-term, strategic goals. In health, education, and governance, donors have responded to other vexing problems with more agile and locally driven programs, sometimes referred to as “doing development differently.” This approach requires a move away from donor-driven solutions and toward ownership at all levels of the process, with local practitioners enabled to experiment, learn, and lead the way toward impactful solutions.

The media crisis is indeed complex and intricately interwoven with other challenges, but a growing group of actors involved in media development and in international funding are signaling that complexity is no excuse for inaction. Solutions to this crisis will require that political agency rise to the daunting level of the challenge, and that the structures of international cooperation—forged as the global response to World War II and refined through the successful efforts to prevent a return to devastating nuclear conflict—are now put into motion to safeguard the foundations of independent media.

Pathways and Entry Points to Improve Media Support

This report was originally prepared as a background paper for the 2019 meeting “Confronting the Crisis in Independent Media,” and has since been updated to reflect the outcomes of that gathering. In the run-up to the meeting, CIMA conducted background research to identify existing and potential pathways for donors to respond to the multi-faceted crisis confronting media and governance.

This report was originally prepared as a background paper for the 2019 meeting “Confronting the Crisis in Independent Media,” and has since been updated to reflect the outcomes of that gathering. In the run-up to the meeting, CIMA conducted background research to identify existing and potential pathways for donors to respond to the multi-faceted crisis confronting media and governance.

Media today can easily be seen as all-encompassing. This paper, however, is concerned with news media’s function in the public interest: as a sentinel, a watchdog, an infomediary, and a public platform. Despite the radical changes occasioned by the spread of digital communication technologies, these functions still depend fundamentally on the ability of societies to protect basic rights to freedom of expression and access to information and to sustain the ethics and core practices associated with independent journalism, no matter how it is funded.

The objective of the research was to understand the strategies undertaken by donor organizations trying to strengthen the media’s public service function and to draw lessons from their experiences. The findings are aimed at those organizations that wish to operationalize policy commitments, provide new forms of support in response to emerging challenges, or strengthen the effectiveness of current assistance, which totals about $600 million annually from both official and private development assistance.5

The impetus for this research originated from discussions with members of the Network on Governance (GovNet which is one of the working groups under the Development Assistance Committee, the forum of official donors who together provide $147 billion in annual development assistance). A broader set of donors and implementers working in the media sector—both public and private—quickly expressed interest in joining this conversation. In interviews at bilateral, private, and multilateral institutions conducted for this report, donors described how they are already exploring opportunities to provide more effective and long-term support to the media sector, pursuing two broad pathways to achieving these goals: 1) Building multi-stakeholder coalitions and networks for sustainable media ecosystems, and 2) leveraging governance and development agendas for media development.

The research highlighted the obstacles most frequently encountered in these efforts, particularly those related to limited human resources and weaknesses in the cooperative structures of aid, but also strategies for overcoming them. The research concludes that opportunities exist to call attention to and build knowledge around media support and to promote greater coordination across donors in the sector. The report will refer to these opportunities as “entry points” because they are, in effect, the on-ramps to the two pathways. The term “entry points” also serves as a useful shorthand for the complex constellation of international commitments and frameworks, existing networks and relationships, shared objectives and interests, and operational capacities that create such opportunities.

The pathways and entry points do not constitute a blueprint. On the contrary, they are intended as a tool to assess how—in a given context or on a given issue—the demand for media development support can be better articulated and connected to the structures of international cooperation. Donors must also contend with the challenge of how to provide effective support in two especially difficult contexts: conflict-affected and fragile states; and closed and illiberal states. Not only do these contexts require distinct approaches, they also present unique operational challenges that are addressed separately in this report.

The following section elaborates on the pathways and entry points, highlighting the ways donors are using these entry points. The section also presents insights into how donors can more effectively respond to the media crisis in difficult contexts. This is followed by a section entitled “From Entry Points to Action” that describes some of the most salient possibilities for action, highlighted both by CIMA’s research and by participants of the 2019 meeting in Paris.

Pathway 1: Building multi-stakeholder coalitions and networks focused on media ecosystems

Multi-stakeholder coalitions and international networks are an essential pathway to identify and deliver solutions to the complex challenges confronting media systems. Where they exist, coalitions provide opportunities to work in a more strategic and coordinated manner on these issues, and to build the political will needed to sustain progress. These coalitions are working to promote enabling environments and sustainable sources of journalism, which provide citizens with the information and analysis they need, when and how they want it. Coalitions have also formed to uphold the principles of an open and accessible internet, where all citizens can freely express themselves, share and debate ideas, and engage in economic activities.6

Media sector-focused coalitions, however, remain uneven. Many developing countries do not have multi-stakeholder coalitions capable of engaging effectively with national policy-making processes and development agendas on media issues, and these country-level coalitions and actors are still unevenly connected to the efforts of regional blocs and international networks. In several multi-stakeholder coalitions focused on other governance issues, the media industry is often little mobilized or not included. Still, there is substantial evidence of what determines a coalition’s success, and how such coalitions can be supported.

National coalitions

Our research indicates strong demand for support to broaden and diversify local networks and encourage multi-stakeholder and multidisciplinary engagement. Where these efforts exist, donor country offices have had greater opportunities to support the media sector and have enhanced the effectiveness of that support. Examples from Latin America, South Africa, the United States, and elsewhere attest that these coalitions must have a wide base, including actors engaged in other change efforts, such as women’s rights groups and legal system reformers.7 These coalitions can make a significant contribution with modest support to catalyze and strengthen them.

Small amounts of support for research and strategic discussions helped to propel the efforts in Uruguay that influenced a host of laws related to community radio, libel, and freedom of information. Similar support was helpful to the efforts leading to the 2013 changes in Mexico’s telecommunications law.8 In Burma, a multi-stakeholder approach begun in 2013 sought to involve relevant actors beyond the sector: local community leaders, companies, government officials, and international and regional stakeholders. Though the Burmese case also highlights the challenges of convening such forums in an uncertain transition, the relationships developed at the time laid the groundwork for a variety of coalitions and campaigns around the country’s second draft of the Right to Information Bill and new provisions in the Telecommunication Act. It also contributed to the development of the Myanmar Journalism Institute, as well as a safety fund for journalists.9

Regional coalitions

Regional networks and coalitions have been growing in Latin America,10 Southeast Asia, Europe, and Sub-Saharan Africa11 with relatively small investments in research, workshops, and coordination. These regional networks are crucial intermediaries between the national and the global and an important source of learning and capacity development. Regional networks can also drive national reform efforts, especially when they can tap into regional inter-governmental structures and collaborate with regionally focused NGOs.

In Latin America, these networks have been bolstered by the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression at the Organization of American States and by connections made between the growing network of media freedom advocates, regulators, and judicial groups. For instance, in the process of providing a massive online course to over 8,000 judiciary workers, and in the efforts to mainstream freedom of expression curriculum into judicial schools, UNESCO discovered that with modest additional efforts, it could further consolidate a cross-country coalition dedicated to ensuring that the judiciary is a defender of these basic rights in the region.12

In Africa, regional coalitions have developed in clusters, frequently associated with the economic blocs on the continent such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and Southern African Development Community (SADC). ECOWAS, in particular, has emerged as the leading regional economic institution on issues of democracy, civil society, and good governance in Africa, as illustrated by its decisive intervention to end the Gambian political crisis in 2016. The Media Foundation of West Africa has been one of the key players working to organize civil society groups, media councils, regulators, and legal groups, among others, to take advantage of the political opportunity to build a regional strategy for media development.13

The Center for International Media Assistance, Deutsche Welle Akademie, and International Media Support, among others, have been working to foster these coalitions in the Global South.14 Meanwhile, organizations such as Reporters Without Borders and the European Journalism Centre are currently engaged in regionally focused network-building, dialogue, and advocacy on the specific challenges facing investigative journalists across Europe. These institutions have been deeply involved in working with donors to understand and address new threats and offer lessons for other regions.

Global coalitions

As global decisions—including those made by private, transnational companies—increasingly shape the media environment, international coalitions have become crucial. These global coalitions, however, often depend upon strong regional coalitions to be effective. By the same token, these global networks can also provide some of the opportunities, incentives, and knowledge needed to activate or strengthen national and regional action.

Media and free expression advocates have found cause to come together globally in response to urgent issues such as the growing incidence of internet shutdowns and site blocking, but are also increasingly working to build a shared advocacy agenda and long-term goals, including current efforts at the Internet Governance Forum to establish a “Dynamic Coalition” tasked with leading on the issues at stake in technical standard debates for media freedom and freedom of expression.15 The UN’s Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists, for instance, has provided an incentive for coalition-building among media advocates, including for the work in Latin America described above.

The challenge of disinformation16 and various “trust” initiatives17 have also provided a platform for global coalition building, though these efforts have not had adequate representation from the Global South. Efforts to cultivate knowledge on the issues of media ownership and regulatory controls are also making progress, both methodologically and as an approach to reform.18 Meanwhile, high-profile individuals are also finding ways to exert pressure, including through the Information and Democracy Commission.19 Overall, such efforts could be expanded and strengthened with greater support and through opportunities to link these various issues to the sustainability (or viability) of independent media.

Pathway 2: Leveraging governance and development agendas for media development

The public service functions of media—public sentinel, infomediary, and public platform—are crucial to governance and development, yet governance support to the media sector has been rather limited, frequently restricted to the promotion of freedom of expression and access to information laws and to the reform of laws that run counter to media freedom, including criminal libel laws. Official donors spent an average of $80–90 million each year on support for laws and policies that promote media freedom in the years 2010–2015, a paltry sum given the growing challenges that arose during this period.20

A number of opportunities exist to integrate media into governance agendas—nationally and internationally—that can strengthen these legal reform efforts and create an agenda for more holistic and long-term action in the sector. Better integration of media support into national development agendas can also create opportunities to tap into broader governance funding streams—which totaled about $19 billion annually in the 2010–2015 period, according to figures from the OECD-DAC.21

National governance agendas and international development frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (in particular, SDG 16) provide opportunities for coordinated efforts that could be leveraged to improve support to the media sector. These opportunities are enhanced by global efforts to promote open and accountable government and citizen engagement for good governance currently led by the World Bank, OECD, UNDP, and the Open Government Partnership, among others. At the country level—particularly in transitional democracies—the background research identified a number of avenues to more effectively integrate media development into national and regional governance and development agendas.

Support for institutions that govern and regulate the media sector

Key informants who were interviewed for this research expressed interest in developing new processes, strategies, and coordinating mechanisms to approach media support in a more holistic and sustainable way. Many donor organizations acknowledge that media assistance needs to support long-term development and the stability of media institutions, in addition to the training for journalists and content production that currently comprise at least a third of all international support to the media sector.22 Meanwhile, support also remains largely short-term: the Global Forum for Media Development, a membership organization representing media development organizations, reports that most of its members operate on funding cycles of one to two years.23

Donors indicated an interest in more guidance and knowledge on how effectively to support capacity development of the national institutions that shape media systems. Recognizing that in a developing country context such institutions can even be complicit in undermining pluralism and independence in the media sphere, some donors and implementers have chosen to disengage. This challenge, however, is not unique to media development; international support efforts have also had to contend with the politics of engagement in other sectors. Confronting the media crisis will require independent institutions that can fairly and effectively govern and regulate media, including media councils, telecommunications and spectrum regulators, anti-monopoly authorities, self-regulatory bodies, journalist associations, blogger associations, universities and training centers, among others.

Additionally, our research found that there is a desire to expand traditional diagnostic processes (such as those used by the World Bank) to incorporate a better understanding of how a media ecosystem is affected by new laws and frameworks, market regulation, and specific issues such as spectrum management. More in-depth analysis of these issues, which might be perceived as tangential to governance or development outcomes, can provide opportunities to support vital actors or new entrants, anticipate emerging trends or threats, and bridge gaps across sectors.

Integrating media development into support for open government and transparency

The growing attention to open government and transparency creates opportunities for integrating media into the governance agenda, including when governments themselves seek international assistance in the field of media and communication. The increased willingness by actors within the media industry to discuss their struggles has also opened up an opportunity to mobilize support for the sector.

The growing attention to open government and transparency creates opportunities for integrating media into the governance agenda, including when governments themselves seek international assistance in the field of media and communication. The increased willingness by actors within the media industry to discuss their struggles has also opened up an opportunity to mobilize support for the sector.

For instance, the OECD’s recent efforts to support the governments of Tunisia, Morocco, and Jordan in public communication have highlighted the weaknesses within those media systems that would need to be resolved for government communication to be effective. The OECD is currently cultivating partnerships in those countries to formulate broader strategies for support to the media sector.

The Open Government Partnership (OGP) is an example of a multilateral initiative that has established a multi-stakeholder process that offers another potential entry point. Since its inception in 2011, the OGP has expanded to nearly 80 countries, which have made over 3,000 commitments to open government reforms. Those commitments to date have seldom included objectives related to the media sector, but that is beginning to change. In Mongolia, Ghana, Ukraine, and Jordan, the OGP has been used as a platform for integrating media development objectives into the open government agenda.

At a meeting at the World Bank in August 2018, senior bank officials suggested that if national partners are able to put media issues higher on national development agendas, the World Bank could use its governance and operational portfolios to better engage in the efforts to build vibrant and well-governed media systems for development. With stronger country-level demand, more opportunities could be created on media governance issues, not only for World Bank advisory services and country dialogue, but also for its lending mechanisms. This could expand space for sector diagnostics and research to underpin national media development efforts, and for technical assistance to regulators overseeing media markets and government procurement affecting the sector.

Social accountability work, an approach that often focuses on supporting the development of capacities for citizen participation in monitoring local service delivery, could also make more meaningful connections to media development. Usually, social accountability initiatives engage with the media in instrumental ways, though support exists at the Global Partnership for Social Accountability and elsewhere to pursue a more transformative agenda by recognizing that local, independent media are not just a channel, but also an agent of social accountability in their own right.

More effective responses to government demand for institutional reforms in the media sector

Opportunities exist to foster greater government demand for media sector reform and development, and to respond with holistic and long-term forms of support when such demand does materialize. The OSCE, UNDP, World Bank, and OECD are among the players that could help to coordinate support to the media sector in response to government demand.

Government demand emerges in a number of different scenarios. In times of political transitions— such as those recently in Tunisia, Burma, Sierra Leone, and Ethiopia—governments have expressed a desire for international cooperation to strengthen government communication, open the media sector, and reform state broadcasters.

In these cases, rigorous and detailed country-level diagnostics have been an essential resource for enabling media-related work, as was the case for the World Bank in Mozambique and Madagascar, and for the OECD in Tunisia.24 That demand has been further cultivated by the presence of multi-stakeholder forums, as in the cases of Sierra Leone and Burma.

Where donor organizations have worked with governments on media development, however, seldom do these efforts get elevated into the governance agendas in ways that promote coordination. Furthermore, support packages frequently neglect a number of crucial aspects for successful reform, including the ability of regulators to assess the democratic outcomes of their decisions or to apply anti-trust laws to media markets. Such multi-disciplinary, policy-oriented capabilities are essential for successful reform. Still, opportunities presently remain for donors to formulate broader, more coordinated packages of support in countries such as Ghana, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Mongolia, and Jordan.

Media development as part of long-term electoral support

Many of those interviewed for this research discussed the opportunities and challenges that are linked to the increased attention that the media receives before and during elections in countries. Election typically produce heightened interest in (and resources for) coordination and engagement in dialogue across sectors, and a more acute understanding of the role the media can play in electoral outcomes. That said, funding for media work during elections has been inadequate. As recently as 2012, media and journalism remained one of the lowest priorities in electoral aid packages, according to a report by UNDP.25

Efforts around elections in countries such as Burma, Rwanda, Kenya, and Ukraine brought examples of opportunities to bring attention to the role of media institutions such as media councils and public broadcasters, and created openings to develop cross-sectoral programming around media education and literacy issues.

While election-related support offers opportunities for engagement, activities around elections are subject to short attention spans, with support and coordinating efforts starting immediately before and quickly dissipating after elections. Amid broader efforts to reframe electoral support as a long-term commitment, media-focused activities also need structures for on-going coordination.

Challenging Environments: Closed and Fragile Contexts

The entry points above are most accessible in countries where there is adequate civic space for coalitions to form and where champions of reform exist within government agencies. The response to the media crisis, however, must find strategies to support the development of independent media and an open internet even in environments where neither civic space nor internal champions can be found.

Support for media development in closed and illiberal states

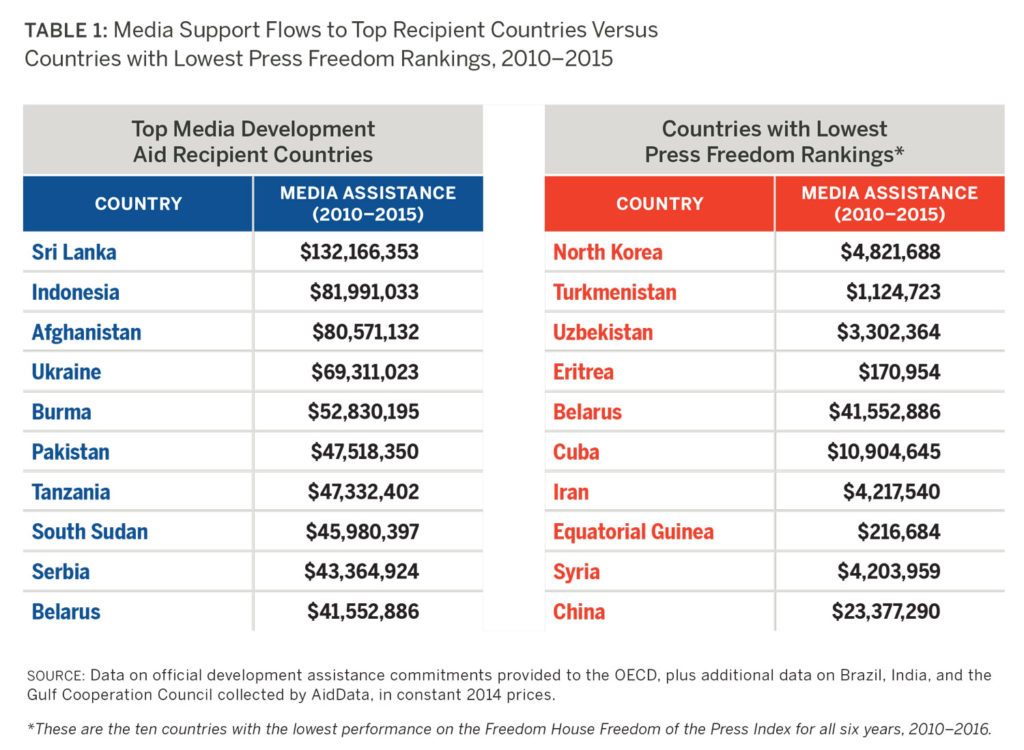

In closed and illiberal states, it is unlikely that either governance reforms or national-level stakeholder networks will provide an entry point for media support. In these environments, private foundations, civil society coalitions, and regional mechanisms operating under the umbrella of civil rights and democratic freedom, however, could provide new opportunities for strategic and coordinated efforts, and for establishing methodologies for responding more effectively to the often sudden and unexpected openings, as occurred in Tunisia and, more recently, in Ethiopia. According to CIMA’s analysis of aid flows, support for media is frequently weakest in these environments.26

It is natural that funding would be lower in these environments as the risks and dangers to both grantees and donors are much higher. The ability of donors to support local actors and build coalitions is constrained within these environments with limited civic debate and cultures of fear. In addition, good practice and wider aid coordination is nearly impossible when support has to be concealed. However, our research uncovered several potential areas for expansion of donor activity and attention to these countries and contexts.

Indirect forms of support are frequently more feasible in closed and illiberal environments. Historically, donors have provided grants to exile media, or supported their own public broadcasters to report and transmit in local languages. However, other indirect approaches exist, including support for legal defense, virtual and physical security measures, and the hosting of secure servers and communication platforms.

As described above, one of the benefits of support to regional mechanisms, coalitions, and institutions includes the potential for support from across borders, especially from countries that are relatively more open than their neighbors. In addition, support to strategic litigation at the regional level has been successful in a variety of difficult circumstances, such as recent court decisions from the ECOWAS Court of Justice on laws in the Gambia that criminalized speech27 or the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling that Venezuela could not dismiss public servants for political speech and activities.28

Interviews from public and private donors alike suggest the opportunity for greater coordination and engagement across donors in these contexts. Private foundations, while making up a much smaller piece of the overall funding pie, offer some comparative advantages in these contexts such as increased appetite for risk, less bureaucratic decision-making structures and potential for rapid response, the ability to supply smaller investments into local entities, and the ability to innovate new approaches to the structure and distribution of funding. Partnerships with organizations such as the Media Development Investment Fund, which offers expertise in media investments in difficult political contexts, can continue to be explored by larger public donors.

Coordination among donors in these environments has some precedents, including the Burma Donor Forum, which operated until 2012 (not to be confused with the Myanmar Working Group, which formed later). Such mechanisms should develop guidelines for ensuring that support does not prejudice the independence of outlets or distort media markets. These groups should also develop a longterm roadmap and capacity among grantees in the event of a political transition, including for how exile media can safely reintegrate into national media systems.

Support for media development in conflict‑affected and fragile contexts

The peace-building agenda provides entry points in conflict-affected, fragile, and fractured states, though successful coordination and multistakeholder processes in these contexts requires distinct approaches and institutional capacities.

Media has been a significant, if often poorly strategized, component of programming in conflict-affected and transition contexts. Indeed, support for media in conflict-affected states was among the fastest growing areas within media development assistance in the 2010– 2015 period.29 Particularly substantial investments were made in building media systems and infrastructures following the invasions of Afghanistan30 and Iraq31 in 2001, with mixed results. A brief re-intensification of media support followed the 2011–2012 Arab uprisings; more recent grants of this nature—frequently in the millions of dollars—have targeted South Sudan, Pakistan, and Syria.32

Though the figures indicate growing attention to media in such fragile environments, the position of media and communications within these contexts can be narrow in scope and often siloed. Diverting attention away from media support capable of holding government to account has been, ironically, one of the main consequences of military and other security-focused institutions giving greater attention to media and communication.

The role of media and communications continues to be poorly integrated into country diagnostic systems, including political economy, governance, and conflict analyses. Proper integration and then appropriate strategic follow-through of media and communications environment concerns would mitigate this. In Sierra Leone, for instance, following the departure of the UN peacekeeping mission in 2013, the Media Reform Coordinating Group has provided a platform to continue the work of legislative reform and building media capacities.33

Furthermore, support to media in these settings can frequently come to an abrupt end, without considerations for sustainability. For instance, the integration of media and communications considerations into electoral planning, particularly across the electoral cycle, remains very limited despite readily available tools and systems to enable this and explicit demand from many electoral commissioners and other electoral management bodies.

From Entry Points to Action

The entry points described above create important opportunities for greater and more effective support to the media sector, but further work is needed to turn these opportunities into an action plan. The background research for this report and the subsequent discussion in Paris produced a number of recommendations for concrete, actionable steps (a few of which are already being taken). Those recommendations underpin three strategic objectives; these objectives and their corresponding recommendations are outlined here and further elaborated below.

- Build the high-level will and donor capacity needed to increase support to the media sector

a. Garner multi-country, high-level support for this agenda

b. Explore a global fund for media development and an international media development partnership to better coordinate the demand for media development

c. Invest in internal and shared expertise, including for country-level donor representatives who often need guidance on media reform topics

- Strengthen approaches to international cooperation focused on the development of media sector institutions

a. Support coalition-building, from the national to the global

b. Strengthen the institutions that govern and enable media development

c. Support knowledge building on the politics and institutions of media development

- Enhance the effectiveness of media sector support by making it more demand‑driven and coordinated

a. Develop models for the integration of media development into national governance and development agendas

b. Bolster coordination opportunities for donors, their development partners, and media stakeholders at the national level

c. Improve data on international media assistance

d. Leverage the SDGs to coordinate support for the media sector

f. Establish coordination groups for support to media in illiberal states

g. Integrate media into diagnostics and long-term objectives in fragile contexts

Objective 1: Build the high-level political will and donor capacity needed to increase support to the media sector

Garner multi-country, high-level support for this agenda

Addressing the weaknesses in global media and journalism systems will require high-level political will and leadership. Fortunately, many governments are beginning to make the push, including the foreign ministries of the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and France, among others. Regional blocs such as the OAS and ECOWAS are also putting media issues higher on the political agenda,34 while media development coalitions and international implementers are exerting their own pressure and marshaling crucial evidence and expertise. Many organizations are planning to use key upcoming events to push the topic of media development to a higher political level. These events include the OECD Ministerial Meeting in May; a summit in July in London co-hosted by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development; and, also in July, the SDG High-Level Political Forum in New York. Such joint efforts targeting key meetings are being coordinated through existing pipelines, including the GovNet, SDG-focused coalitions, and others.

Addressing the weaknesses in global media and journalism systems will require high-level political will and leadership. Fortunately, many governments are beginning to make the push, including the foreign ministries of the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and France, among others. Regional blocs such as the OAS and ECOWAS are also putting media issues higher on the political agenda,34 while media development coalitions and international implementers are exerting their own pressure and marshaling crucial evidence and expertise. Many organizations are planning to use key upcoming events to push the topic of media development to a higher political level. These events include the OECD Ministerial Meeting in May; a summit in July in London co-hosted by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development; and, also in July, the SDG High-Level Political Forum in New York. Such joint efforts targeting key meetings are being coordinated through existing pipelines, including the GovNet, SDG-focused coalitions, and others.

Explore a global fund for media development and an international media development partnership

A number of possible modalities exist for pooled or cooperative funding in this area. This includes the possible creation of a global fund for media development of similar engagement as other thematic development funds, which could increase funding, consolidate practices, stream-line reporting requirements, and address other structural issues. A sector-wide approach to harmonization could also be encouraged through a number of discrete initiatives. An effort is already underway to scope out the feasibility of such a fund, including its purpose and precise financing modality. In the event that such a fund is created, however, it will be vital to ensure that it does not magnify the shortcomings of donor-driven approaches. This issue could potentially be addressed by fostering an international media development partnership focused on helping local organizations coordinate country-level demand and build coalitions for reform.

Invest in internal and shared expertise, including for country-level donor representatives

Donors have consistently cited internal constraints imposed by limited human capacity and low levels of media-specific expertise and networks within key departments and at the country level. Each donor is advised to have at minimum one person responsible for coordinating and advancing media sector development, and country-level governance specialists should have better understanding and exposure to media issues. Collectively, donors could invest in a help desk or knowledge services provider, like the highly-respected Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, that can consolidate and share existing knowledge and lessons in the field. This could be perhaps be linked to an initiative with a greater ambition of generating new knowledge and stimulating innovation. In the short term, and much less ambitiously, donors agree on the need for a simple and authoritative set of guidelines, emphasizing do-no-harm principles, for the growing number of funders working in the media sector.35

Efforts by the EU’s Media4Democracy technical assistance initiative and the Swiss Development Corporation’s Thematic Unit on Democratization, Decentralization, and Local Governance, among other initiatives, seek to build institutional structures for actors across the organization to develop capacity around media, request expertise, produce research, and distribute information. These kinds of thematic internal coordinating initiatives offer one way to confront the challenges related to the decentralized nature of media assistance programming across large public institutions and to build institutional political will around media support.

Objective 2: Strengthen approaches to international cooperation focused on the development of media sector institutions

Support coalition building, from the national to the global

National coalitions can be bolstered with support to well positioned groups that can conduct research, carry out broad-based consultations, and work across institutional boundaries to formulate an agenda and strategy for reforms in the media sector. With core funding, cross-border coalitions and regional groups—particularly when working in conjunction with regional blocs or other regional mechanisms—can integrate media into broader governance agendas, build political will, strengthen capacity, and exert influence in countries with less conducive environments for media development. These coalitions also need better representation in global efforts to shape internet governance and the commercial foundations of news, and can be more effectively leveraged with regard to global normative frameworks, such as the SDGs. As mentioned above, support for these coalitions could ultimately take the form of an international media partnership of sorts, perhaps modeled after examples in other governance fields, such as the International Budget Partnership or Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative.

National coalitions can be bolstered with support to well positioned groups that can conduct research, carry out broad-based consultations, and work across institutional boundaries to formulate an agenda and strategy for reforms in the media sector. With core funding, cross-border coalitions and regional groups—particularly when working in conjunction with regional blocs or other regional mechanisms—can integrate media into broader governance agendas, build political will, strengthen capacity, and exert influence in countries with less conducive environments for media development. These coalitions also need better representation in global efforts to shape internet governance and the commercial foundations of news, and can be more effectively leveraged with regard to global normative frameworks, such as the SDGs. As mentioned above, support for these coalitions could ultimately take the form of an international media partnership of sorts, perhaps modeled after examples in other governance fields, such as the International Budget Partnership or Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative.

Strengthen the institutions that govern and enable media development

Unmet demand exists for support to strengthen media councils, journalist associations, regulators, and other institutions critical to media development. Donors with a track record of providing this support should expand these efforts. Support for the governing institutions in the media sector will also be strengthened through better integration of media development into national governance and development agendas. Approaches and expertise emanating from governance support in other sectors, such as those related to market regulation and government procurement, should be tested and adapted in the media sector as part of this integration.

Support knowledge building on the politics and institutions of media development

Linked to the above, donors, implementers, networks, and local groups possess experience and knowledge that has not yet been adequately documented or shared on how to build multi-stakeholder coalitions and strengthen the enabling institutions of the media sector. Indeed, this learning, innovation, and knowledge sharing is stifled by inadequate attention to the media sector among the researchers, think tanks, and other thought leaders—in both recipient and donor countries— that provide multi-disciplinary analysis for international development efforts. A multi-donor agreement could help to sustain a knowledge hub, consortium, or some other institutional arrangement to lead on the learning agenda and get governance researchers engaged in these discussions.

Objective 3: Enhance the effectiveness of media sector support by making it more demand-driven and coordinated

Develop models for the integration of media development into national governance and development agendas

Donors might initially agree to focus support for multi-stakeholder governance approaches in the media sector in a few key countries where demand for media reform is strong. This approach could help develop modalities and transparent and inclusive diagnostic processes that could be mainstreamed for integrating media development/reform into the governance agenda. These efforts should encourage cross-donor strategies of support, promote long-term objectives, and be driven by multi-stakeholder forums and multi-disciplinary knowledge, including where those already exist on issues of open government, transparency, and electoral support. In addition to working with governmental and civil society partners, these efforts should aim to involve the private sector in proposing business environment reforms that promote open competition, fair access to finance, competition in advertising and ownership, and incentives for media partnerships. Such efforts could make the sector more attractive to private sector investment, including social impact investing. All of these efforts could be supported by improved guidelines for coordination, approaches to media sector diagnostics, lessons learned, and best practices. Several donors suggested that these guidelines

Donors might initially agree to focus support for multi-stakeholder governance approaches in the media sector in a few key countries where demand for media reform is strong. This approach could help develop modalities and transparent and inclusive diagnostic processes that could be mainstreamed for integrating media development/reform into the governance agenda. These efforts should encourage cross-donor strategies of support, promote long-term objectives, and be driven by multi-stakeholder forums and multi-disciplinary knowledge, including where those already exist on issues of open government, transparency, and electoral support. In addition to working with governmental and civil society partners, these efforts should aim to involve the private sector in proposing business environment reforms that promote open competition, fair access to finance, competition in advertising and ownership, and incentives for media partnerships. Such efforts could make the sector more attractive to private sector investment, including social impact investing. All of these efforts could be supported by improved guidelines for coordination, approaches to media sector diagnostics, lessons learned, and best practices. Several donors suggested that these guidelines

Bolster coordination opportunities for donors, their development partners, and media stakeholders at the national level

While nationally led coalitions should provide leadership for strategic and long-term media sector goals, donors will also need to foster opportunities for coordination at the country level. This often becomes most clear when independent media is targeted by repressive governments, or when media reforms are introduced. Efforts to coordinate media support should ideally take advantage of existing modalities and platforms for coordinating governance support. Countries such as Ethiopia, Afghanistan, and Rwanda, for instance, already have well-established mechanisms for donor coordination. In countries with less clear paths, a joint diagnostic process, supported collectively or through a chosen convening body, could provide the basis for future coordination, including through a “division of labor” or sector-wide approach to funding.

Improve data on international media assistance

Coordination efforts would be aided considerably by improving the data available on media sector funding, an issue participants agreed to raise the OECD. At the moment, media assistance—aid intended to strengthen the media sector itself—is reported to the OECD’s database under as many as five different codes. Furthermore, even within these codes, media assistance is frequently conflated with forms of support serving very different purposes, such as public diplomacy or strategic communication. This makes it difficult to track and coordinate aid to media development.

Leverage the SDGs to coordinate support for the media sector

The implementation, monitoring, and review of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development provides important opportunities for donor coordination and for building political will for media development.36 The 2030 agenda provides a number of opportunities to raise awareness of the contribution that independent media makes to development, and to deepen the analysis of its role in ensuring the achievement of the SDGs. Support for SDG implementation should prioritize a broader and freer flow of public information on both the national and global level on progress towards each of the 17 SDGs and their 169 associated “targets,” including but not limited to Target 16.10, which commits all UN members to “protect fundamental freedoms” (including press freedom) and “ensure public access to information.”

Bilateral and multilateral development programs can also promote coordinated efforts through the voluntary national assessments of the status and effectiveness of access-to-information laws and the overall “enabling environment” for independent media and the free flow of information. These parallel assessments, already underway in at least 20 countries with support from UNESCO, rely not just on official data but also on inputs from civil society, academia, and the media as well.

Establish coordination groups for support to media in illiberal states

Approximately 21 countries received the lowest press freedom ranking (“very serious situation”) in Reporter’s Without Borders’ 2018 World Press Freedom Index. Each of these would be a potential candidate for a donor coordination group that could host a gathering at least once per year to draw political attention to the press freedom situation in these countries and to convene a closed-door meeting for donors to coordinate their funding. Such groups would benefit from guidelines for ensuring that support does not prejudice the independence of outlets or distort media markets, and the members of these groups should cooperate to ensure a long-term roadmap and capacity among grantees in the event of a political transition.

Integrate media into diagnostics and long‑term reforms in fragile contexts

At the outset of efforts to design stabilization strategies in conflict-affected contexts, diagnostics to assess the risks to social cohesion should more systematically recognize media as a complex driver of conflict and contemplate forms of support that go beyond trainings in conflict-sensitive journalism, peace-messaging, and the set-up of UN-run radio networks. These efforts should be on-going and flexible, and integrated with broader efforts to rebuild institutions of governance, including for electoral processes, and build the capacity and the momentum for national groups to carry forward an agenda of media development and reform after stabilization efforts have concluded.

Acknowledgements

This report is the product of many contributors. It draws from background research conducted by Laura Schwartz-Henderson, Bill Orme, Paul Rothman, and James Deane, and from research assistance and other vital contributions from Kate Musgrave and Malak Monir. CIMA’s Senior Director Mark Nelson provided leadership, feedback, and guidance from start to finish. This document also reflects input from all of the participants of the January 31–February 1, 2019, meeting “Confronting the Crisis in Independent Media,” though most especially from Kristin Olson, Sarah Lister, Corinne Huser, and Will Taylor.

Photo Credits:

Banner Image: RobinJP / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

Footnotes

- The Varieties of Democracy dataset maintains nine distinct media-related indicators; one of those indicators specifically tracks the extent to which news media is critical of the government. This indicator reached its apex in 2012, and many of the other eight variables (with the exception of a binary variable on the existence of internet in the country and one giving an estimated percentage of women working in the media) also begin to decline in the years 2011–2014

- The Freedom House’s global index indicates press freedom fell to its lowest point in 13 years in 2017. Longitudinal public opinion surveys such as the Edelman Trust Barometer, AmericasBarometer, and Afrobarometer all indicate a general decline in public trust in the media. And measures of quality and sustainability, such as IREX’s Media Sustainability index, also point to a deteriorating environment for independent media.

- Myers, M. and Juma, A., 2018, Defending Independent Media: A Comprehensive Analysis of Aid Flows, (Washington, D.C.: Center for International Media Assistance).

- For an overview of “information disorder,” see Wardle, C. and Derakhshan, H., 2017, Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making, (Strasbourg: Council of Europe); for a brief overview on how media development must contend with deliberate efforts to undermine the information space, see Kalathil, S., 2019, “Transnational Authoritarian Threats to Independent Media,” in International Media Development: Historical Perspectives and New Frontiers, Benequista et al. (eds), New York and London: Peter Lang Publishing.

- This figure is an estimate based on private donor contributions listed in Media Impact Funder’s dataset and on CIMA’s analysis of official aid flows published in Myers, M. and Juma, A., 2018, Defending Independent Media: A Comprehensive Analysis of Aid Flows, (Washington, D.C.: Center for International Media Assistance).

- This figure is an estimate based on private donor contributions listed in Media Impact Funder’s dataset and on CIMA’s analysis of official aid flows published in Myers, M. and Juma, A., 2018, Defending Independent Media: A Comprehensive Analysis of Aid Flows, (Washington, D.C.: Center for International Media Assistance).

- 7 On Latin America, see: Segura, M.S. and Waisbord, W., 2016, Media Movements: Civil Society and Media Policy Reform in Latin America, (London: Zed Books). For South Africa, see: Teer-Tomaselli, R., 2011, “Legislation, Regulation, and Management in the South African Broadcasting Landscape: A Case Study of the South African Broadcasting Corporation,” in R. Mansell & M. Raboy (Eds.), Handbook on Global Media and Communication Policy, (London: Blackwell Publishers). On the United States, see: Byerly, C., & Ross, K., 2006, Women and Media: A Critical Introduction, (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing).

- On Uruguay, see: Rothman, P., 2014, “Uruguay’s Media Reform Success Story,” CIMA Blog, July 30, available at https://www.cima.ned.org/blog/uruguays-mediareform- success-story/. On Mexico, see: Abraham- Hamanoiel, A., 2016, “A Perfect Storm for Media Reform: Telecommunications Reforms in Mexico,” In D. Freedman, J. Obar, C. Martens, & R. McChesney (Eds.), Strategies for Media Reform: International Perspectives, (New York: Fordham University Press); and Dragomir, M., 2016, “Media Reform in Mexico,” In D. Freedman, J. Obar, C. Martens, & R. McChesney (Eds.), Strategies for Media Reform: International Perspectives, (New York: Fordham University Press).

- https://www.mediasupport.org/where-wework/#myanmar

- Podesta, 2016, Media in Latin America: A Path Forward, (Washington, D.C.: Center for International Media Assistance).

- Wasserman, H., & Benequista, N., 2017, Pathways to Media Reform in Sub‑Saharan Africa: Reflections from a Regional Consultation, (Washington D.C.: Center for International Media Assistance).

- Orme, B., 2018, School for Judges: Lessons in Freedom of Information and Expression from (and for) Latin America’s courtroom, (UNESCO: Paris).

- Tietaah, G. and Braimah, S., 2019, A Regional Approach to Media Development in West Africa, Recommendations from a Consultative Process (Washington, D.C.: Center for International Media Assistance and the Media Foundation for West Africa).

- CIMA’s efforts to stimulate regional efforts through consultations are described here: https://ned.cima.org/ resources/regional-consultations

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1hMclf0hz2PXa_VhOl7w2iRhFpvi-NZ0yeY2mJCN6QBA/edit

- The Misinfocon gathering (https://misinfocon.com/) has spawned numerous cross-border collaborations since it was first held in 2017.

- https://www.cima.ned.org/blog/trustworthy-media-timedistrust-no-silver-bullet-search/

- Media Ownership Monitor and Media Power Matrix

- https://rsf.org/en/news/rsf-launch-groundbreaking-globalinformation-and-democracy-commission-70-years-afterun-general

- Based on an estimate calculated from figures available in Myers, M. and Juma, L., 2018, Defending Independent Media: A Comprehensive Analysis of Aid Flows, (Washington D.C.: Center for International Media Assistance).

- Myers and Juma, 2018.

- Ibid.

- GFMD, 2019, “Recipient perceptions of media development assistance: A GFMD study,” (Brussels: Global Forum for Media Development).

- See World Bank, 2017, “Media and Service Delivery in Mozambique and Madagascar”; and OECD, 2018, “Open Government in Tunisia.”

- UNDP, 2012, “Evaluation of UNDP Contribution to Strengthening Electoral Systems and Processes,” (New York: UNDP), 21.

- https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/comprehensiveanalysis-media-aid-flows/

- https://www.mediadefence.org/news/update-ecowascourt-delivers-landmark-decision-one-our-strategic-caseschallenging-laws-used

- https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/cases/san-miguel-sosa-v-venezuela/

- Based on an estimate calculated from figures available in Mary Myers and Linet Angaya Juma, 2018, Defending Independent Media: A Comprehensive Analysis of Aid Flows, (Washington D.C.: Center for International Media Assistance).

- See Page, D and Siddiqi. S, 2012, The Media of Afghanistan: the challenges of transition, BBC Media Action Policy Briefing No. 5.

- See Awad, A and Eaton, T, 2013, The Media of Iraq ten years on: the problems, the progress, the prospects, BBC Media Action Policy Briefing No. 8.

- Myers, M and Juma, Linet, 2018.

- Jacob, R.B., 2019, UNDP’s Engagement with the Media for Governance, Sustainable Development and Peace. (Oslo: UN Oslo Centre).

- The OAS was a leading partner in the 2015 regional consultation on media reform held in Bogota (see Podesta, D. 2016, Media in Latin America: A Path Forward), and has recently pivoted to work on more current, hot‑button media issues such as disinformation and fake news (http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/expression/ showarticle.asp?artID=1128&lID=1). For ECOWAS’ involvement in the media sector, see Tietaah, G. and Braimah, S., 2019, A Regional Approach to Media Development in West Africa.

- Guidelines of this nature exist, notably the American Press Institute’s guiding principles for funders of nonprofit media (https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/ publications/nonprofit-funders-guiding-principles), but could usefully be adapted for international funders and communicated by an authoritative source like the OECD.

- See UNESCO and UNDP, 2019, “Entry points for media development to support peaceful just and inclusive societies and Agenda 2030 — a background discussion note.”