Executive Summary

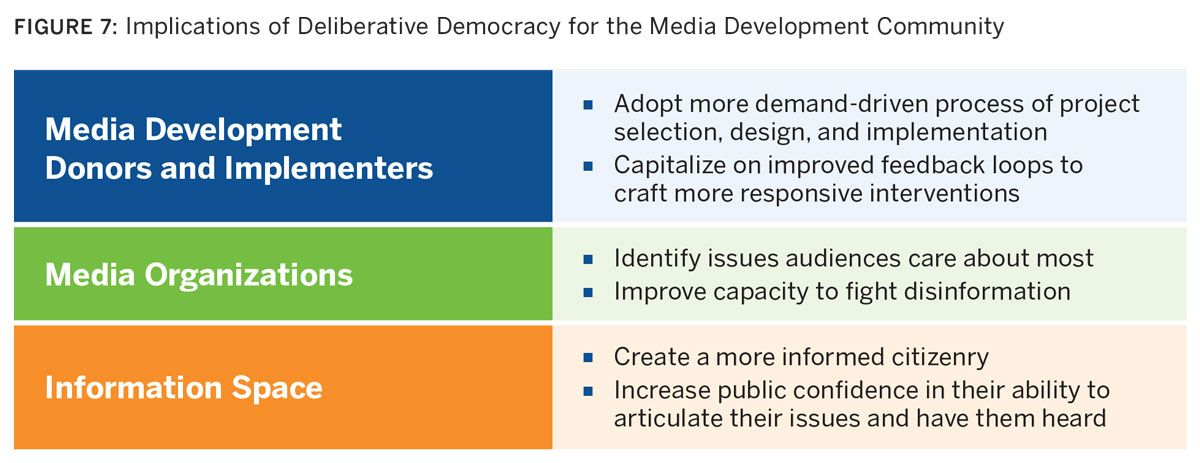

An innovative new set of citizen engagement practices—collectively known as deliberative democracy—offers important lessons that, when applied to the media development efforts, can help improve media assistance efforts and strengthen independent media environments around the world. At a time when disinformation runs rampant, it is more important than ever to strengthen public demand for credible information, reduce political polarization, and prevent media capture. Deliberative democracy approaches can help tackle these issues by expanding the number and diversity of voices that participate in policymaking, thereby fostering greater collective action and enhancing public support for media reform efforts.

Through a series of five illustrative case studies, the report demonstrates how deliberative democracy practices can be employed in both media development and democracy assistance efforts, particularly in the Global South. Such initiatives produce recommendations that take into account a plurality of voices while building trust between citizens and decision-makers by demonstrating to participants that their issues will be heard and addressed. Ultimately, this process can enable media development funders and practitioners to identify priorities and design locally relevant projects that have a higher likelihood for long-term impact.

– Deliberative democracy approaches, which are characterized by representative participation and moderated deliberation, provide a framework to generate demand-driven media development interventions while at the same time building greater public support for media reform efforts.

– Deliberative democracy initiatives foster collaboration across different segments of society, building trust in democratic institutions, combatting polarization, and avoiding elite capture.

– When employed by news organizations, deliberative approaches provide a better understanding of the issues their audiences care most about and uncover new problems affecting citizens that might not otherwise have come to light.

Introduction and Overview

Government and development actors have long recognized the power that collective intelligence and citizen participation can have in designing effective policies and building trust. For this reason, deliberative democracy principles are increasingly promoted to capture public sentiment and incorporate it into democratic and governance initiatives. However, the media development sector has yet to widely integrate this approach into projects and programs designed to build and support independent media systems in developing countries and new democracies. Given the news media’s essential role in supporting the accountable governance and engaged public debate that democracy demands, media development actors should take advantage of innovative deliberative democracy initiatives to bolster their efforts

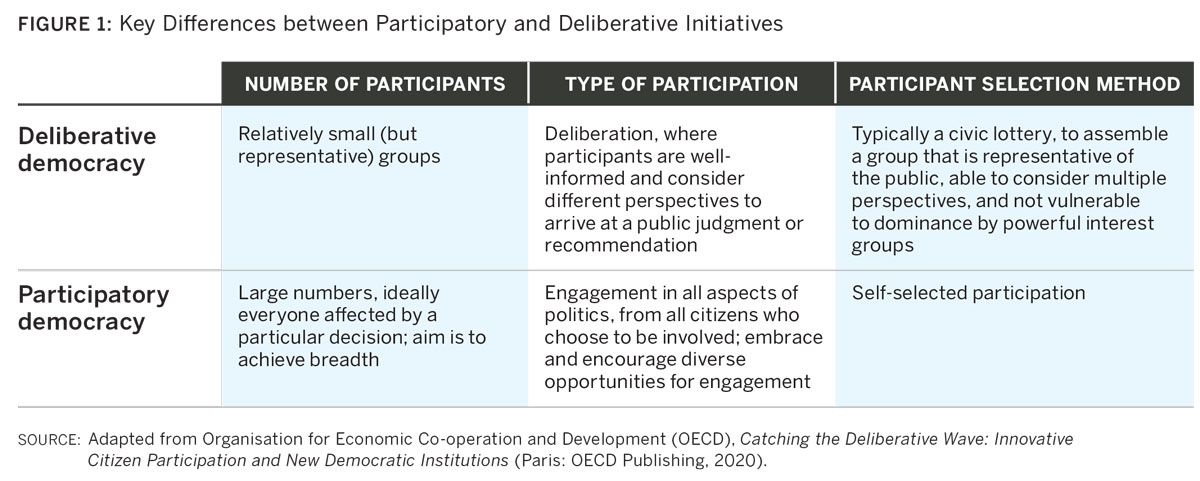

Deliberative democracy approaches represent a subset of broader efforts to foster public participation in policymaking. They are characterized by two defining features: deliberation and representativeness. First, they aim to foster an open and informed discussion in which a variety of policy options are weighed and evaluated and specific actions are recommended. Second, these initiatives seek to include a representative sample of participants from the broader community or society. In this way, “deliberative” approaches can be distinguished from more general “participatory” approaches that encourage citizen input in a variety of forms.1

Given the essential role of an independent and pluralistic media sector in establishing and maintaining democratic rights and freedoms, expanding and applying deliberative approaches to media development can support democracy more broadly. Deliberative initiatives could help media outlets ensure that the issues they cover are relevant to the public, thereby building public demand for information. They could also help media assistance stakeholders determine the best pathways and approaches for interventions aimed at supporting media system reform. Finally, deliberative processes could be leveraged to counteract the challenges posed by disinformation and polarization, build public trust in independent news and information, and create demand for a plurality of voices and perspectives.

Given the essential role of an independent and pluralistic media sector in establishing and maintaining democratic rights and freedoms, expanding and applying deliberative approaches to media development can support democracy more broadly. Deliberative initiatives could help media outlets ensure that the issues they cover are relevant to the public, thereby building public demand for information. They could also help media assistance stakeholders determine the best pathways and approaches for interventions aimed at supporting media system reform. Finally, deliberative processes could be leveraged to counteract the challenges posed by disinformation and polarization, build public trust in independent news and information, and create demand for a plurality of voices and perspectives.

The implications of using deliberative processes for media development

center on three primary themes:

How media development practitioners can use these processes to

How media development practitioners can use these processes to

design and build support for their interventions, as well as how they

can support the use of deliberation in target countries- How media organizations themselves can use deliberative

engagements to improve coverage and tackle important

and emerging issues - How media organizations can be more involved in deliberative

processes (that do not necessarily have to be concerned with

media issues directly) to share information, highlight benefits of the processes, and counteract misinformation and disinformation

Deliberative democracy initiatives have thus far been primarily used in more stable democracies, though their benefits are just as relevant—if not more so—in countries that are in transition and are in the process of building democratic traditions, institutions, and norms. These exercises “reinvigorate civic life by building citizens’ capacity to engage in other types of civic activities, as participants are more likely to talk about politics and volunteer in the community.”2 Literature on democratic transitions highlights the importance of inculcating democratic values and practices in the hearts and minds of citizens,3 a process that deliberative democracy can support. Political actors in countries around the world are increasingly recognizing the value of such approaches, spawning recent growth in the use of deliberative initiatives. In many cases, nongovernmental organizations and academics have pioneered the application of deliberative processes and have galvanized support among governments to continue and expand their use.4

There is an opportunity, therefore, to extend the virtuous cycle that deliberative processes can bring to other sectors and countries, particularly developing countries and those undergoing democratic transition. There is also an opportunity for the media development community to leverage best practices from deliberative processes to help increase the relevance and effectiveness of interventions designed to support independent media. Through deliberative initiatives, the media development community could design more effective, representative, and inclusive approaches and policies that are more responsive to local contexts and are driven by local actors. Furthermore, deliberative processes can help foster the citizen engagement needed to build and sustain democratic media systems, and ensure that media organizations can fulfill their role in providing citizens the information they need to fully participate in democratic life.

From Public Participation to Deliberation—a Theoretical Background

It is important to take a step back and understand how increasing public participation in policymaking fits in the larger context of good governance reforms. The push for “participatory democracy” developed in the modern era from the civil rights and women’s liberation movements of the 1960s, which demanded greater civic engagement in government decision-making.5 The value of increased participation is also relevant to debates within political theory. For instance, by establishing participation as a human rights issue, economist Amartya Sen noted that even if participation fails to produce good decisions, it is still valuable in that it provides a space for the public to make their views heard. Ensuring that the public can engage in the policymaking process underscores the importance of promoting literacy, civic knowledge, and media freedom.6

Practically, philosopher Jürgen Habermas argues that participation, and deliberation in particular, produces higher-quality decisions. He contends that deliberation emphasizes the quality of arguments over power dynamics, ultimately leading to outcomes that are more “just” and more “rational.”7 Participation also improves information flows and feedback loops, which can promote policies that are more responsive to the realities of citizens and can counteract top-down or prescriptive interventions. Therefore, “consensus-building, open dialog, and the promotion of an active civil society are key ingredients to long-term sustainable development.”8

International organizations have long recognized the need to integrate participatory processes into development efforts. In 1994, the World Bank expressed its support of “government efforts to promote an enabling environment for participatory development.”9 Additionally, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) Recommendation on Open Government specifically notes that governments should grant all stakeholders “equal and fair opportunities to be informed and consulted and to actively engage them in all phases of the policy-cycle” (Provision 8). The OECD’s recommendation also holds that governments should develop “innovative ways to effectively engage with stakeholders to source ideas and co-create solutions” (Provision 9).10

The importance of pluralistic and independent media to bolster participatory development processes is also gaining traction. For instance, the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) Strategy on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance highlights the importance of independent and open media systems as a cornerstone of efforts to promote participatory processes and foster engaged and informed citizenries.11

Deliberative Initiatives—What They Are

As a broad concept, striving to increase participation is worthwhile. However, increasing participation in and of itself is not particularly useful for identifying and guiding specific actions. Fostering opportunities for direct engagement in the policymaking process without careful consideration of who the participants are, or what mechanisms are used to engage them, can reproduce or magnify power imbalances. Citizens with the time and financial ability to engage, and those who represent powerful interests, can have an outsized impact on what is discussed and decided upon.

For example, in São Tomé and Principe, a national forum on how to spend oil revenues shows how an ill-considered design can enable certain actors—in this case, moderators of community meetings— to have undue influence. The government put in place a national dialogue that offered every adult citizen the opportunity to attend public meetings, where they learned about the country’s oil reserves and discussed how oil revenues might be spent. The results of the discussions were then presented to the national government. However, follow-up studies on the results of the dialogue found that even though the leaders of groups were randomly assigned by the organizers, the organizers’ influence on the outcomes was significant. Notably, group leaders’ opinions appeared to account for many of the views recorded in community meetings. The studies demonstrate that the preferences of the groups aligned with the preferences of the discussion leaders, rather than those of the participants.12 Rather than being an indictment of deliberative processes, however, this case highlights the value of putting in place structures that can ensure the needs and desires of a target population are represented accurately. It also shows the importance of designing processes in ways that limit the influence of leaders and moderators; for example, by bringing in outside experts to help inform discussions and structuring the discussions around a clear framework that focuses on specific trade-offs.

For example, in São Tomé and Principe, a national forum on how to spend oil revenues shows how an ill-considered design can enable certain actors—in this case, moderators of community meetings— to have undue influence. The government put in place a national dialogue that offered every adult citizen the opportunity to attend public meetings, where they learned about the country’s oil reserves and discussed how oil revenues might be spent. The results of the discussions were then presented to the national government. However, follow-up studies on the results of the dialogue found that even though the leaders of groups were randomly assigned by the organizers, the organizers’ influence on the outcomes was significant. Notably, group leaders’ opinions appeared to account for many of the views recorded in community meetings. The studies demonstrate that the preferences of the groups aligned with the preferences of the discussion leaders, rather than those of the participants.12 Rather than being an indictment of deliberative processes, however, this case highlights the value of putting in place structures that can ensure the needs and desires of a target population are represented accurately. It also shows the importance of designing processes in ways that limit the influence of leaders and moderators; for example, by bringing in outside experts to help inform discussions and structuring the discussions around a clear framework that focuses on specific trade-offs.

By offering processes that more accurately reveal needs and more deftly weigh trade-offs, deliberative initiatives aim to counteract social inequities in ways that other more generally participatory opportunities (such as community hearings, public fora, referenda, public commenting) have overlooked or ignored. Generally, “deliberative democracy is a [process by which] collective deliberation is central and in which participants formulate concrete, rational solutions to social challenges based on information and reasoning.”13 It is based on the idea that there are better and worse answers to many decisions, and it is designed to tap into the collective intelligence and diversity of a group to identify better policies.14 It is also important to note that the term “deliberation” is used intentionally, and is distinguished from other similar processes, such as debate, which aims to persuade rather than find solutions, and dialogue, where the emphasis is on respectful exchange rather than on decision-making.15

In practice, there is a set of characteristics that differentiates deliberative mechanisms from other participatory activities (see FIGURE 1). As outlined in a recent OECD report, and as reflected in earlier academic literature, the features that characterize a deliberative process include the following:

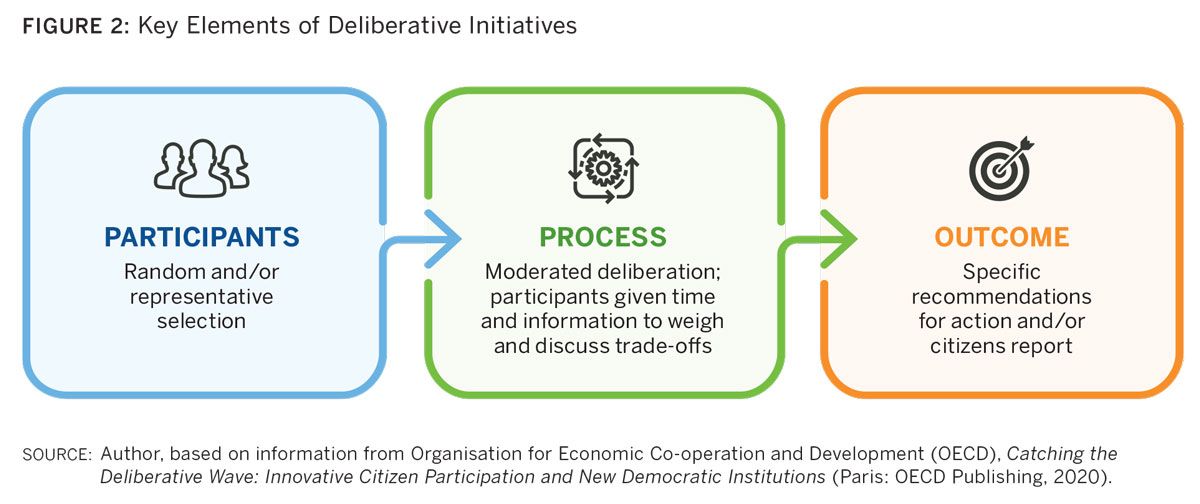

- A focus on participant selection, with a goal of ensuring participants broadly match the demographic profile of the community (this is often achieved through random selection, or sortition)

- Space for moderated deliberation, in which participants are given information and time to discuss the topics; moderation of the conversations; and an agreed-upon framework and clear questions around which participants can weigh trade-offs and reach a group decision or set of recommendations

- Measurable impact, meaning decision-makers (whether governments or other convening bodies) agree to respond to or otherwise act on the outcomes of the process16

Deliberative processes work well for a wide range of difficult and contentious questions. By relying on a representative group, encouraging listening, using evidence, taking time for reflection, and developing constructive outcomes (see FIGURE 2), they enable informed and values-based discussions that can help tackle complex and potentially controversial matters. Deliberative processes are particularly useful for issues that require balancing trade-offs, as well as those that do not necessarily have obvious solutions or easily identified correct answers. Deliberation also facilitates tackling long-term issues that go beyond electoral cycles, as it is designed to limit the impact of political parties and elections and to provide incentives for participants to prioritize the public good.17

That said, most examples of deliberative initiatives are from countries that do not receive development support. Organizers of deliberative activities in developing country contexts need to account for the specific democratic challenges many of these countries face, such as a sense of disenfranchisement due to weak democratic or participatory traditions, communication challenges (such as illiteracy or multiple local languages), transportation and funding issues, and a lack of organizer capacity to act on the recommendations. Nevertheless, as the examples will show, and as research has confirmed, development projects need local support and engagement to be successful. That is precisely why deliberative processes could play an invaluable role in international assistance agendas and strategies. By ensuring that interventions are demand-driven and adapted to local contexts—for example, by relying more on voice and video materials for information provision where literacy rates may be low— funders and implementers can help ensure initiatives achieve their goals.18

In addition to broader development agendas, the strengths of deliberative processes align with the media development sector’s calls for greater collaboration and cooperation between stakeholders. In particular, “dialogues with strong public sector participation provide a prominent platform for engagement between political leaders and nongovernmental stakeholders, who are often left out of the conversation, to discuss challenges and opportunities for building independent media systems.”19 For media assistance actors, deliberative events could therefore focus on how to design “effective locally-driven and long-term” development strategies, as well as serve as a platform for knowledge sharing.20

Expanding the use of deliberative initiatives as a part of media development efforts could also bolster efforts to counteract the declining trust in public institutions that countries around the world are facing. In OECD countries, only 45 percent of citizens trust their governments.21 These data echo the Edelman Trust Barometer’s findings that 47 percent of people from a global sample trust government. Media institutions are similarly facing a crisis of trust globally.22 Historically, these are relatively low marks. Over time, low levels of trust in public institutions reduce social cohesion, exacerbate polarization, reduce public engagement, and contribute to the rise of radicalization.23

Lower trust in public institutions may help cause, and in turn be caused by, a widespread reduction in civic space, as reflected in countries placing increasing limitations on citizen agency, participation, and fundamental freedoms such as those of assembly and speech.24 As discussed in more detail below, deliberative processes can be part of the effort to counteract these trends. Furthermore, and notable for countries in transition, they can heal historical divisions due to the explicit emphasis on discussing policy priorities, values, and tradeoffs. Importantly, studies have found that deliberation is particularly useful in societies that have suffered from tensions between ethnic, religious, or ideological groups.25

Lower trust in public institutions may help cause, and in turn be caused by, a widespread reduction in civic space, as reflected in countries placing increasing limitations on citizen agency, participation, and fundamental freedoms such as those of assembly and speech.24 As discussed in more detail below, deliberative processes can be part of the effort to counteract these trends. Furthermore, and notable for countries in transition, they can heal historical divisions due to the explicit emphasis on discussing policy priorities, values, and tradeoffs. Importantly, studies have found that deliberation is particularly useful in societies that have suffered from tensions between ethnic, religious, or ideological groups.25

It is important to keep in mind that there is no “right” model for deliberative initiatives. The choice to use a specific design primarily depends on the time and resources, level of governance, and policy area.26 Indeed, given how rarely deliberative practices have been used for media development, there is an opportunity to build on ongoing, broader participatory processes to incorporate deliberative practices.

For example, in Ethiopia, the government arranged a national public consultation concerning media regulation reforms. While this process was not designed to be deliberative according to the definition outlined in this report, the initiative did seek to include as many stakeholders as possible, including journalists, representatives of media organizations, a range of government and political representatives, public communication officers, and the public.27 The challenges this process faced were related to reaching a large segment of society on a limited budget, and ensuring participants saw their comments reflected. Despite these challenges, the use of public consultation expanded the public’s role in the country and suggests that incorporating deliberative components into ongoing participatory initiatives could be a useful model; indeed, an effective approach for media development practitioners might be to identify ongoing participatory efforts and add on or integrate deliberative elements.

Taken together, the benefits of deliberative processes suggest that they can be especially valuable in response to the global challenges to democracy. The role they can play in supporting media, as a key pillar of democracy, should also be explored further, as “the decisions about the structure of the media ecosystem. . . are critical public policy issues that affect many other aspects of the overall governance environment and the definition of the public sphere.”28 The next sections will therefore look at key benefits of deliberative processes and suggest how to expand their use in media development.

Deliberative Democracy in Practice

Several deliberative initiatives are particularly applicable to the media development sector, holding the potential to:

- enhance citizen participation in public decision-making and restrain elite capture of decision-making processes;

- help media outlets themselves ensure that coverage informs citizens and responds to their needs;

- limit the spread of disinformation and moderate polarization; and

- build public confidence in democratic processes and institutions.

Through the examples that follow, we begin to see how these processes, when done well, can produce better policies. Moreover, increasing public understanding of and participation in policymaking—thereby building confidence that policies reflect and respond to citizens’ demands—will chart a path for the media development community to apply these processes in ways that help promote democratic governance more widely.

Enhancing Citizen Engagement and Limiting Elite Capture

Deliberative processes can generate practical, real-world benefits to policymakers and donors. The initiatives discussed below from Ghana and Malawi aimed to help identify local needs and direct donor funding, while the example from Mexico includes lessons for how deliberation can help restrain elite capture of the policymaking process. While these cases do not focus on media development, the experiences and lessons learned can be applied by media assistance actors to help foster multi-stakeholder and demand-driven approaches.

Case 1: Deliberative Polling in Tamale, Ghana, and Nsanje District, Malawi

In 2015, a network of universities conducted a Deliberative Poll in Tamale, Ghana, the country’s third-largest city. Deliberative Polling is a twist on public opinion research that brings together a random, representative sample of citizens and engages them in deliberation on target issues or policy changes. Selected participants are first polled on the issues and then invited to engage in dialogue with each other and with competing experts and political leaders based on questions they develop in small group discussions with trained moderators. The event concludes with a questionnaire that captures the participants’ final opinions, and outcomes are shared with the public and media.29

In Tamale, the Deliberative Poll helped local government and donor agencies identify the most pressing needs in the community, with a focus on issues related to water, sanitation and hygiene, livelihoods, and food security. The process brought together 208 participants, split into 15 groups, over two days. At the end of the initiative, the top proposals agreed on by participants included promoting education focused on cholera control, implementing a plan to control mosquitoes, and intensifying a hand washing campaign in schools. The targeted recommendations highlight the group’s ability to offer specific policy solutions that address Tamale’s development problems.30

As important as the policy outcomes are the process of deliberation itself had a measurable impact on the opinions of participants, as evidenced by the fact that many of them changed their views in statistically significant ways after the deliberative process. Moreover, “the results do not seem to have been dominated by more advantaged groups, and the participants became demonstrably more informed.”31 This illustrates the power of deliberative processes to help participants weigh trade-offs and propose specific policies that respond to their priorities.

The Deliberative Poll in Tamale also shows how “a random sample of the public, chosen to consider the issues in depth, can provide a useful form of participation for policy ownership by the people in a developing country.”32 Despite challenges related to poverty and relatively low levels of education compared with countries where deliberation is typically used, participants were capable of making hard choices and identifying preferred policies.33

Similar to the example from Ghana, a Deliberative Poll was organized in the Nyachikadza and Ndamera Traditional Authorities of the Nsanje District of Malawi, focusing on issues related to relocating and resettling communities affected by flooding, reducing economic vulnerabilities, managing population pressures, and supporting better access to social services. Subsequent research on the impacts of this exercise demonstrates that the process of deliberation served as a useful counterpoint to other consultations the participants had been involved in, where input was limited and there was inadequate opportunity for two-way discussion, learning, and dialogue. Participants also predominantly agreed that they “learned a lot about people very different from me.” Finally, the process influenced policy options, as half of the prioritized policy options changed significantly after deliberation.34

Case 2: Avoiding Elite Capture in Oaxaca, Mexico

One of the primary reasons deliberative initiatives can reveal policy preferences and benefit from the wisdom of the crowd is that, when designed well, they can prevent elites or powerful voices from capturing the policymaking process. An example from Oaxaca, Mexico, helps illustrate this. In Oaxaca, several municipalities have maintained “traditional” political authority mechanisms, whereby many government decisions are decided in assemblies via collective deliberation. Attendance at these annual or biannual assembly meetings is often high, and the sessions take place over the course of hours or days.35 In addition to the deliberative aspects, these traditional processes are transparent and their outcomes are visible to the community. While the political conditions in Oaxaca cannot be replicated, the benefits provided by the space that citizens are given to deliberate and to direct policy implementation can be.

Compared with Mexican communities governed by elected political parties, traditionally managed communities have been found to allocate public goods (e.g., water and sanitation) more equitably and distribute public goods in a way that tends to favor the poor. In the communities with elected officials, the provision of public goods “tends to favor households aligned to the mayor’s party.”36 Additionally, citizens appear to be better informed about public affairs in municipalities using traditional mechanisms, “largely due to their active participation in community assemblies and deliberation regarding the allocation of public funds. Better informed citizens, in turn, appear to be associated with more accountable local leaders.”37

Compared with Mexican communities governed by elected political parties, traditionally managed communities have been found to allocate public goods (e.g., water and sanitation) more equitably and distribute public goods in a way that tends to favor the poor. In the communities with elected officials, the provision of public goods “tends to favor households aligned to the mayor’s party.”36 Additionally, citizens appear to be better informed about public affairs in municipalities using traditional mechanisms, “largely due to their active participation in community assemblies and deliberation regarding the allocation of public funds. Better informed citizens, in turn, appear to be associated with more accountable local leaders.”37

Overall, researchers argue that traditional processes support broader engagement in decision-making, greater local government accountability, and public cooperation in a way that promotes the well-being of the community. The study concludes that “indigenous communities, when ruled by traditional leaders, norms and practices,” generate more effective and fair policy outcomes, in part by preventing elites from capturing decision-making.38 Similar results were seen in the Deliberative Poll in Ghana discussed above, as that process also prevented more advantaged members of the community from dominating the outcomes.39

It should be noted that the traditional political processes in Oaxaca do not meet all deliberative criteria. For example, while participation is widespread in Oaxaca, it is not designed to be representative, and while participants are given time for deliberation, there are no external moderators or institutionalized mechanisms for information sharing. The key, however, is that compared with processes that do not typically allow for extensive engagement, the public involvement and potential for impact in Oaxaca clearly helps generate responsive policies and builds accountability and trust among citizens.

These cases demonstrate the potential for deliberative initiatives to balance trade-offs, foster collaborative decision-making on development priorities, and, more broadly, increase engagement and trust in the policy process among citizens. Not only does a more representative sample of voices help deliver better policies, but promoting diverse views is also an essential component of effective governance and rule of law.40 By strengthening the voices of otherwise marginalized or underrepresented groups, bringing new voices into the political process, and restraining elite capture, deliberative processes can indeed make a difference in developing and transitional countries, and for policy areas historically dominated by powerful voices.

Helping Media Outlets Ensure That Their Coverage Informs Citizens and Responds to Their Needs

Deliberative processes can also provide benefits that are specifically relevant to media organizations by providing opportunities to engage with the public on their needs and expectations of what should be covered.

Case 3: Supporting News Outlets to Engage Citizens in Ohio, United States

The Jefferson Center is a nonpartisan, nonprofit civic engagement organization that helps newsrooms connect to new audiences and supports journalists’ efforts to build trust in local media within their communities.41 In 2016, it launched the Your Vote Ohio collaborative—a series of community events focused on helping local news outlets build a better understanding of the types of news and information about political candidates the public would find most useful, and developing representative, community-based news coverage.42

At the outset, the organizers conducted in-depth statewide polls to assess attitudes toward campaigns and media coverage of the 2016 elections. The deliberative process enabled participants to learn how media organizations cover elections, discuss the issues and candidates, and recommend ways journalists could better cover candidates and issues.43 The Jefferson Center also implemented a deliberative initiative to provide space for citizens to interact and communicate with journalists on a variety of issues. The process was modeled after the World Café—a structured discussion format that promotes deliberative conversations to develop recommendations and encourage collective action.44

To date, the project in Ohio has conducted more than 20 of these discussions, bringing together almost 700 participants.45 In September 2018, the project hosted a three-day Citizens’ Jury, consisting of a demographically balanced panel of 23 residents. The participants were asked to discuss how journalists could support “healthy, thriving, and vibrant” communities, specifically related to the state’s drug addiction crisis and the changing economy.46

The organizers reported that these activities helped inform participants and increase their engagement in electoral issues, increased their level of trust in local media, and provided a model for constructive collaboration between citizens and the media.47 For their part, journalists who participated in this process used the information to shift their reporting on these topics to better meet citizen needs and demands. This is most striking in terms of how the journalists covered drug abuse issues. Several community members found the framing and images used in stories about drugs to be generally off-putting, and that the images triggered negative emotional responses. Journalists may have remained unaware of these reactions had they not discussed the topic with the community in a deliberative fashion.

These results show how putting in place a deliberative process can provide a diverse group of community members with a platform to help uncover problems or solutions that are not being reported, reach new communities and sources, illuminate information gaps, and shift coverage toward critical areas to meet citizen demand.48 Together, the examples from the Jefferson Center show the potential impact of deliberative methods for a wide range of actors, such as news media, who can use deliberation to engage directly with the public by using random selection and providing space for deliberation.

Responding to Emerging Challenges: Moderating Polarization and Limiting The Spread Of Disinformation

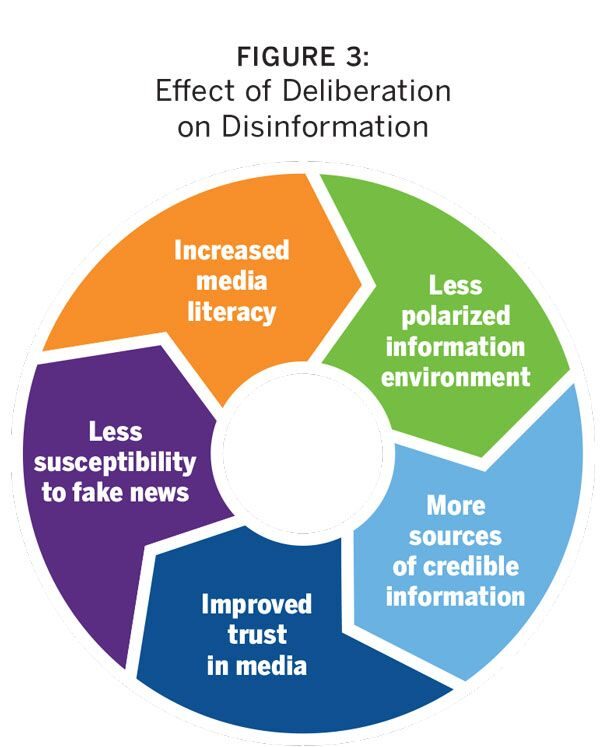

Another benefit of deliberative practices related to information and media ecosystems is their ability to provide a counterweight against emerging threats posed by polarization and the rapid spread of misinformation and disinformation. While a comprehensive exploration of these interrelated challenges is outside the scope of this discussion, this section explores the benefits that deliberative processes can bring in navigating these evolving areas.

Political polarization is a phenomenon that has weakened respect for democratic norms, corroded legislative processes, and diminished trust in institutions of public life around the world.49 There is a risk that individualized information experiences on social media platforms can increase polarization and influence users’ outlooks, especially in politics.50 Moreover, research suggests that while technology and new media platforms may not be the root cause of extreme partisanship and polarization, they can “exacerbate existing problems in the underlying institutional and political-cultural fabric of a country.”51 Furthermore, ongoing attacks on fact-based journalism and expertise (governmental and otherwise) risk reducing trust in traditional institutions of public life and undermining confidence in democratic processes.52

A second emerging challenge is the rapid spread of “disinformation”— false information that is shared knowingly with the intent to cause harm53 —via communication technologies and platforms. The challenge is not so much in the existence of disinformation—lies, exaggerations, and misleading statements have always been a part of public conversation—but more to do with the ways new communication technologies are facilitating its proliferation. Social media in particular is well suited to facilitating the easy and rapid spread of disinformation, since people tend to spread falsehoods “farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth.” This is especially true for false political news.54

A second emerging challenge is the rapid spread of “disinformation”— false information that is shared knowingly with the intent to cause harm53 —via communication technologies and platforms. The challenge is not so much in the existence of disinformation—lies, exaggerations, and misleading statements have always been a part of public conversation—but more to do with the ways new communication technologies are facilitating its proliferation. Social media in particular is well suited to facilitating the easy and rapid spread of disinformation, since people tend to spread falsehoods “farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth.” This is especially true for false political news.54

While media companies, social media platforms, and individuals all have essential roles to play in responding to these changes, governance and policy responses are also critical. The OECD, for example, argues that governments should engage with and respond to these emerging challenges based on the open government principles of transparency, integrity, accountability, and, notably, participation.55 As shown by the experience of the Irish Citizens’ Assembly (see Case 4), deliberative democracy can help counter polarization by tempering positions and producing thoughtful and constructive outcomes. Participants can also serve as effective, informed, and non-expert representatives of the processes and the outcomes for the wider population.

Case 4: The Impact of Citizens’ Assemblies on Political Polarization in the Republic of Ireland

The Citizens’ Assembly was established and funded by the government to help rebuild the relationship between the government and citizens and strengthen the institutions of representative democracy.56 Over the course of two initiatives, almost 200 randomly selected citizens and politicians discussed a number of complex and often divisive legal and policy issues, including reducing the voting age, the role of women in politics, same-sex marriage, electoral reform, abortion rights, how to respond to the challenges and opportunities of an aging population, and climate change. The assemblies resulted in fundamental shifts in Irish policy, including referenda to legalize same-sex marriage and to remove the constitutional ban on abortion.57 The assemblies met key deliberative criteria and were conducted transparently, with wide publication in national media.

With regard to polarization, the organizers of the assemblies found that participants moved toward the center over the course of the deliberations, especially on topics where the breakdown in opinion was evenly split, and that well-reasoned arguments tended to be most effective.58 This tendency toward moderation and constructive conversation is, of course, contrary to the polarized experience of many other public interactions, particularly on social media.

The effect of deliberation on polarized conversation seen in the Irish case is consistent with findings from other experiences, as groups of people that do not share an opinion tend to “depolarize” via deliberation. This is largely due to the ability of genuine deliberation to curb confirmation biases through constructive reasoning.59 Studies suggest that this effect results from the components of deliberative processes that differentiate them from other forms of debate, dialogue, and participation. Taken together, the random selection and diversity of participants, the moderated conversation, and the requirement to engage with trade-offs and develop an informed set of responses impact how groups discuss issues and how opinions develop in ways that help limit polarization.60

Deliberative democracy can also be a powerful tool for reducing susceptibility to disinformation. Encouraging people to use the outcomes of the deliberative process to encourage their own critical thinking is another way that the processes can have a wider positive impact on media and information ecosystems.61 Providing additional sources and inputs that strengthen the information environment can also support independent media functions, as deliberative processes can produce evidence and information that media outlets can use for debunking and fact-checking. The participants in deliberative initiatives can themselves serve as a useful source of trusted, informed, and credible voices to comment on and present policy trade-offs and recommendations.

The Irish example is instructive in this regard, as the organizers found the media coverage to be helpful in offering nuance to the national debate. Talk radio was especially useful, as it provided a venue for participants to discuss their experiences and allowed the public to hear from people like them, thereby emphasizing the citizen-driven nature of the enterprise.62 By relying on a random sample of citizens rather than experts to develop opinions and decisions, deliberative processes “legitimize citizen voices as an influential form of public discourse.”63

The organizers of the Irish Citizens’ Assemblies engaged with journalists as much as possible, as they saw the media as a partner to amplify the conversations within the assemblies.64 The organizers also saw deliberation as a tool to help counteract populist rhetoric by providing informed discussion about the values and rationale behind the recommendations. Follow-up research confirmed that the assemblies were a useful guide for citizens that helped inform electoral decisions.65 As the Irish case shows, the process and outcomes of deliberative initiatives can support media organizations directly, as well as help build stronger information ecosystems that can work against polarization and curb the spread of disinformation.

Building Confidence in Democratic Processes and Institutions of Public Life

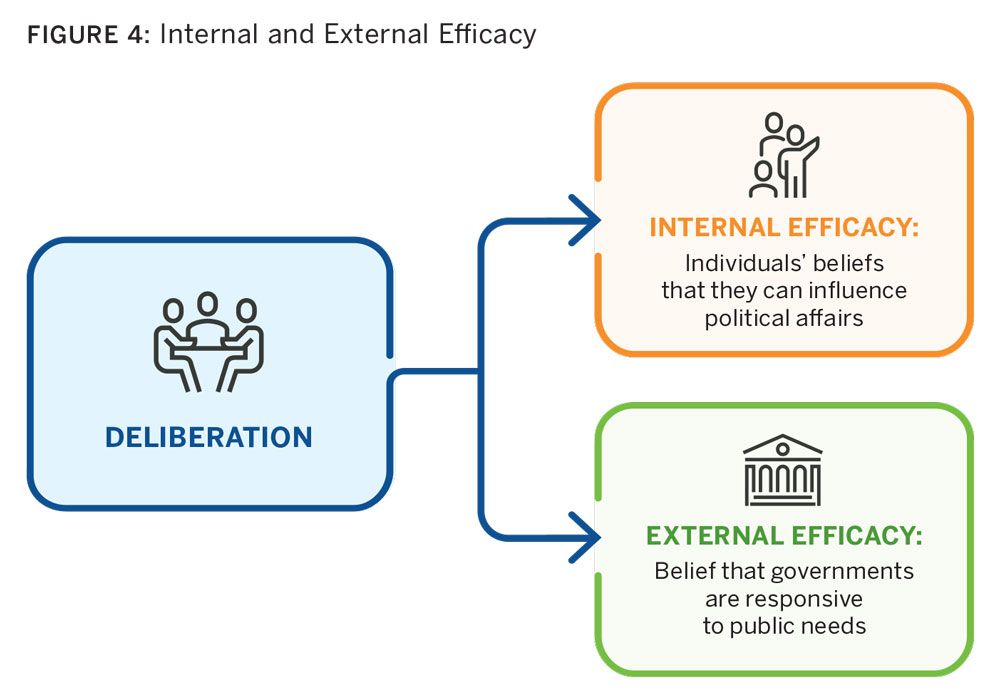

As these cases illustrate, the positive, cumulative effects of deliberative processes can improve the public’s perception of the broader political environment. Research demonstrates that these initiatives strengthen individuals’ self-confidence and competence in the political process.66 Individuals’ beliefs that they are capable of effective political action and that they can understand and influence political affairs is referred to as “internal efficacy,” and deliberation—by bringing ordinary citizens together to consider issues, needs, opportunities, and solutions—is a powerful tool to boost the public’s belief in its own capabilities.67

Deliberative democracy initiatives are also linked to a perception of improved government responsiveness and the belief that governing officials listen to the public, also referred to as “external efficacy.”68 Specifically, deliberation increases external efficacy because the processes illustrate officials’ willingness to cede partial control of their decision-making power.69 In these ways, the potential of deliberative engagement extends beyond the practical considerations and suggests that it can serve as a powerful tool for building citizen confidence in policymaking and planning, thereby enhancing democratic processes.

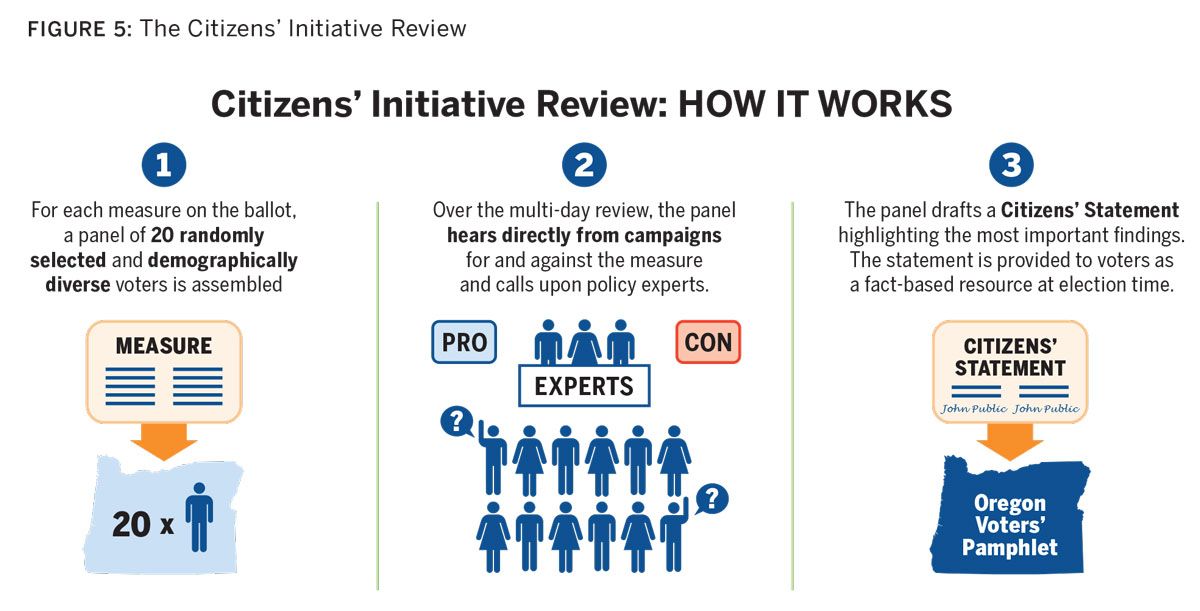

Case 5: Citizen Evaluation of Proposed Ballot Measures in Oregon, United States

A useful example of the benefits to internal and external efficacy comes from the Citizens’ Initiative Review (CIR) in the state of Oregon. This initiative was created by Healthy Democracy, a US-based nonpartisan nonprofit organization, and in 2011 the state legally established it as a permanent part of Oregon’s statewide initiative process.70

The Citizens’ Initiative Review engages citizens in a deliberative process that allows for a public evaluation of proposed ballot measures to supply informed arguments to voters.71 The reviews typically gather two dozen randomly selected citizens for several days of deliberation. Participants assess evidence submitted by each side of a ballot measure and are given space to question campaigners and independent experts. Deliberation is carried out in smaller groups where participants examine costs, benefits, and trade-offs of the proposed ballot measure.72 Based on this deliberation, participants draft a collective statement that explains their rationale and provides key information and arguments in favor of and against the measure.73 The final statement is presented publicly in a press conference and is often included in voters’ pamphlets.74

Independent follow-up research found that “greater exposure to—and confidence in—deliberative outputs was associated with higher levels of both internal and external efficacy.” Specifically, the use of the CIR statements by voters appeared to increase internal efficacy, while mere awareness of the CIR process was enough to improve external efficacy.75 Researchers also found that voters’ beliefs in their ability to influence the outcome—their internal efficacy—grew more among low-interest voters, suggesting that the CIR process may be most useful when it provides new information and perspectives.76 These findings are relevant for developing countries and countries in transition, where citizens may not have a history of seeing their opinions considered or their governments responding to their needs. The findings also demonstrate the potential power of these initiatives to bring citizens closer to their governments.

A few other cases point to the potential that deliberative processes can have on building confidence in the political system. In 2016, ResilientAfrica Network, a network of African universities funded by USAID, organized a two-day Deliberative Poll in the community of Tivaouane-Peulh/Niague, outside of Dakar, Senegal, focused on food security and water and sanitation issues. At the end of the process, participants felt that the event was “extremely valuable,” and in terms of political efficacy, participants felt more strongly—and nearly all agreed—that they had “opinions

about my community that are worth listening to.” The experience also made participants more confident that both the government and their communities would use the recommendations.77 Despite challenges funding the proposed projects, the mayor supported the findings of the Deliberative Poll publicly and worked with relevant ministries and utilities to implement the recommendations, while simultaneously undertaking smaller measures that were in his office’s power to execute.78

The cases from Ireland and Malawi further support the notion that deliberative processes build citizen confidence to participate in public life and enhance trust in democratic institutions. The Citizens’ Assemblies in Ireland increased participants’ interest in politics and their willingness to discuss and become involved in politics. As a result of the assemblies, “participants felt more positive about the ability of ordinary people to influence politics,” in large part because the process ensured that citizens felt their voices mattered.79 There were similar findings in the Malawi case, where participants reported feeling confident the government would take their views into account and that both the government and community would use the results.80

The examples presented demonstrate that well-designed deliberative processes—i.e., those in which organizers are invested and participants can play a constructive role—can help build trust and narrow legitimacy gaps.81 Despite the different contexts and methodologies, these cases suggest that well-considered deliberation can instill a sense of ownership and engagement in policymaking and planning processes among citizens. The buy-in elicited from these processes allows participants, and the public more widely, to feel that those in power—whether governments or international donors—are responsive to their needs, and that decisions are informed by “people like them” rather than made behind closed doors.

Implications for Media Development

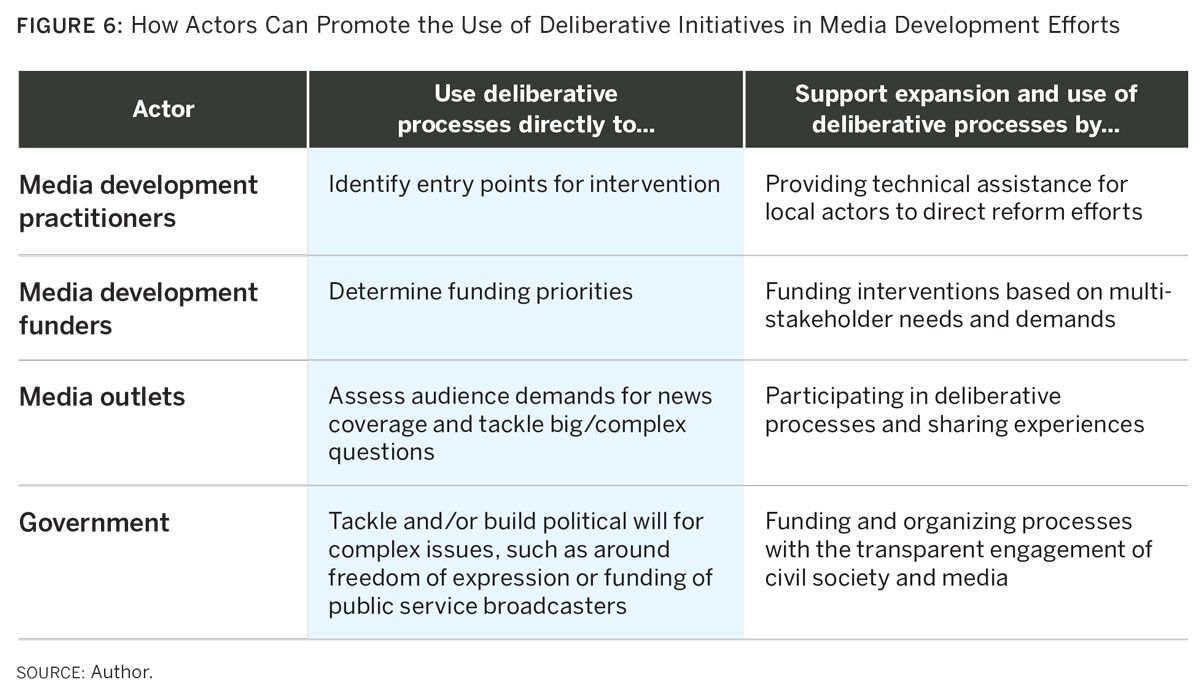

The benefits of deliberative processes that are most relevant for media development include promoting more effective and representative policymaking, restraining elite capture of policymaking and planning processes, informing media coverage itself, counteracting threats posed by political polarization and disinformation, and building confidence in democracy and the institutions of public life. To take advantage of these benefits, this section first considers how prospective organizers of deliberative initiatives might expand their use for media development (see FIGURE 6) and then looks at how such initiatives can counteract key media development challenges.

How Deliberative Processes Can Be Used for Media Development

One straightforward way to expand the use of deliberation in media development is for donors to use these processes directly to build consensus, set priorities, and direct reform efforts and funding decisions. Indeed, development policies may improve if more initiatives were driven by representative and informed deliberation that facilitates buy-in and clarifies sources of resistance. Such benefits are, naturally, also relevant in the context of media development, where deliberative mechanisms provide an opportunity to build public understanding of media policy priorities and allocation of aid in a participatory manner. It is also critical that organizers are committed to at least responding to, if not implementing, the recommendations agreed upon through the deliberative process; given that participants give their time, organizers need to make sure they see the benefit.82

Using these initiatives to help prioritize funding decisions, as in the Ghanaian case, can be a useful way to improve donor effectiveness and offer constructive policy and spending suggestions. Media development practitioners and funders may be well positioned to allocate the resources needed to ensure that processes follow good practices regarding participant selection, moderation, and information provision, and that they lead to clear recommendations and outputs.

Donors could also provide financial support to governments and nongovernmental organizations to help them organize deliberative initiatives. External funding and expertise provided by donors could support random and representative participant selection to help avoid elite or political capture, facilitate the participation of experts, and help publicize and share information on processes and outcomes.

Though deliberative processes are not necessarily expensive, funding poses a particular challenge in development contexts. This challenge was seen in Ethiopia, where the national public consultation relied exclusively on volunteers, negatively impacting staff stability and inhibiting its ability to reach a diverse and geographically dispersed group of citizens.83 Even limited funding support can enable more consistent and widespread engagement opportunities.

In the media sector, where large, government-backed or elite-backed outlets often dominate the markets of developing countries, it could be particularly useful to ensure that a representative sample of participants—including independent, local, or community media outlets, which may struggle to ensure their voices are otherwise heard—are involved.

In addition to direct funding, development practitioners could provide technical assistance to share knowledge and build on existing initiatives. Indeed, the consultative—but not specifically deliberative— case of Ethiopia’s national public consultation concerning media regulation reforms suggests that the opportunity exists to apply good practices around participant selection, information provision, moderation, and outreach to inform future efforts to engage with the public and achieve the benefits that deliberation can bring. In addition to launching new deliberative processes, the experience in Ethiopia suggests that a useful avenue for media development would be to identify opportunities to build on other ongoing initiatives in other sectors. Ultimately, using and expanding upon existing processes can save governments and media development practitioners time and money, as well as leverage existing government and public support for the processes.

As the case study from Ohio illustrates, media development practitioners could also expand the use of deliberation to focus on complex questions that require value judgements and trade-offs related specifically to media coverage issues. Deliberative initiatives can be used to reveal priority areas for media coverage, or consider larger institutional questions, such as media policies, legislation, and financing models. Deliberative processes could also bring together a range of actors to discuss challenges related to identifying new business models, bolstering weak media markets, and preventing threats to editorial independence, among other issues.

Considering the media’s critical role in building public knowledge, promoting transparency, and holding government to account, more fully grasping the needs and expectations of both media organizations and citizens would be valuable. In addition, there is every reason to believe that the benefits of increased internal and external efficacy would play out if deliberative processes were undertaken for supporting media systems. Such initiatives would help identify mechanisms to build or rebuild confidence in, and understanding of, the media as a critical institution of public life. By encouraging public engagement, deliberative processes can build greater trust in, and understanding of, the processes and structures needed to support independent media systems, as well as the role of those structures in supporting democratic governance.

Another consideration is how to support the media in playing a larger role in deliberative processes, even for topics unrelated to media issues. The critical role of a vibrant and plural media sphere in supporting good governance, fostering fair elections, promoting government accountability, and ensuring citizen participation and deliberation cannot be overstated. Engaging the media can promote outreach and knowledge of deliberative initiatives, as well as help build the understanding of innovative democratic practices more broadly. Journalists can help tell the story of the participants in a deliberative exercise and share it with the wider population, as a way of showing the public that “people like me” are involved.84 Involving the media is also consistent with supporting transparency and is crucial to achieving public impact.85 Increasing publicity can help flag the relevance and importance of deliberation and encourage other organizations or government bodies to participate in or develop their own initiatives.86 Building broader understanding and buy-in of deliberative initiatives can help create a mutually reinforcing cycle of increasing the public’s trust in, engagement in, and understanding of democratic processes, while highlighting the media’s central role in supporting them.

How Deliberative Processes Can Help Address Critical Priorities for Media Development

The case studies of deliberative initiatives provide valuable lessons for the media development sector. In particular, the application of deliberative democracy principles could help advance numerous critical priorities for the media development community.

First, such processes can help address calls for demand-driven approaches, which media development experts increasingly see as essential to building and reforming independent media sectors in developing countries and emerging democracies. However, media development assistance often focuses on supply-driven, top-down, technocratic interventions that do not work with local actors to build consensus for reform. Such approaches often fail, as they do little to advance more difficult policy reforms, build strong political foundations and will for independent media institutions, or increase citizen demand for trustworthy information.

Applying deliberative principles in media development efforts can better ensure that interventions are rooted in local demand and help local actors analyze the enabling conditions and prioritize solutions that are based in a society’s governance practices, norms, and institutions. Importantly, deliberative approaches can help ensure that a wide variety of stakeholders—media practitioners, lawmakers, citizens, regulators, civil society advocates, and media investors—are engaged in the process.

The ability for innovative deliberative initiatives to arrive at solutions to complex issues also illustrates their potential to help overcome policy paralysis. Proponents of democratic media reforms often struggle to develop coordinated and coherent policy positions and strategies. Emerging democracies, and developing countries in particular, face immense obstacles in developing coordinated policy positions and effectively implementing policy reforms that support a robust independent media sector. The media sectors themselves in these countries are typically transitioning from state-controlled or authoritarian systems, and governments often lack the political will and capacity to develop and implement policies that defend freedom of expression while also bolstering an open and competitive media market. Such policy paralysis enables media capture—the takeover and control of the news media by entrenched political and economic interests—to thrive.87

Deliberative democracy principles can help actors in these environments develop coordinated policy positions and implementation roadmaps that take local dynamics and limitations into account. For instance, political gridlock can be created by social fractures that may be used to justify putting limits on freedom of expression, weak technical capacity for implementing new policies, or limited public awareness of the benefits of a free media. Overcoming such policy paralysis requires “not only changes in the incentives of actors to pursue reform, but a shift in power, or a shift in the preferences and beliefs of those with power.”88 Often, this shift in power comes from an engaged public that demands increased transparency and greater involvement in the policy process. Deliberative initiatives can help facilitate this.

Photo from CIMA’s regional consultation in Beirut. Experts from 13 countries came together to identify ways to support independent media in the MENA region.

Finally, expanding the use of deliberative approaches to the media development sector could foster coalition-building and create shared agendas for action. Media development efforts are frequently hampered by poor cooperation, competition, and a lack of collaboration between stakeholders. Several global examples demonstrate the importance of multi-stakeholder coalitions to the advancement of media reform efforts.89 As demonstrated by several of the cases in this report, helping local advocates championing media reform engage a broad set of actors, including citizens and civil society, in identifying critical reform issues and charting a path forward can serve to build broad-based public support for change processes.

By strengthening reform coalitions and supporting the development of shared agendas for action, deliberative initiatives can thereby help improve media policy by increasing the diversity of knowledge, perspectives, and experiences reflected in the policy.90 Furthermore, as reflected in the more traditional applications of deliberative democracy, such approaches help improve implementation as citizens gain greater capacity to engage in the policy process and monitor progress.

The ideas laid out in this section serve as a jumping off point for expanding the application of deliberative democracy to the media development sector. There are no one-size-fits-all approaches that can be applied uniformly. That said, in their efforts to connect citizens to the democratic process and to identify and build support for effective policy responses, the media development community can look to deliberative initiatives as both a tool to support their own efforts, and also as part of a wider endeavor to strengthen the foundations of democracy.

Ultimately, such initiatives can help ensure that key issues—such as those around press freedom and the role that the media play in promoting democratic governance—are addressed by inclusive and deliberative mechanisms, not merely by powerful or well-positioned actors. Countries around the world are experiencing rapidly evolving and interrelated threats posed by the public’s increasing lack of trust in public institutions, widening polarization, and the exponential spread of disinformation. In this environment, deliberative democracy is an important tool that reaffirms not only the capacity of the public to critically engage with these issues, but also their ability to create the solutions.

Footnotes

- Claudia Chwalisz, Reshaping European Democracy: A New Wave of Deliberative Democracy (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 2019), https://carnegieeurope.eu/2019/11/26/new-wave-of-deliberative- democracy-pub-80422.

- S. Boulianne, K. Chen, and D. Kahane, “Mobilizing Mini‑Publics: The Causal Impact of Deliberation on Civic Engagement Using Panel Data,” Politics (2020), https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395720902982.

- Katrin Voltmer, The Media in Transitional Democracies (Cambridge: Polity, 2013), ISBN: 978-0-745-64459-2.

- Author interview with Claudia Chwalisz, Policy Analyst, Open Government Unit, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, March 25, 2020.

- Carole Pateman, Participation and Democratic Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970).

- Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1999).

- J. Habermas, The Theory of Communicative Action (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), as quoted in M. Humphreys, W.A. Masters, and M.E. Sandbu, “The Role of Leaders in Democratic Deliberations: Results from a Field Experiment in São Tomé and Príncipe,” World Politics 58 (2006): 583–622, doi:10.2307/40060150.

- Joseph Stiglitz, “Participation and Development: Perspectives from the Comprehensive Development Paradigm,” Review of Development Economics 6, no. 2 (June 2002): 163–82, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1467-9361.00148.

- World Bank, The World Bank and Participation (Washington, DC: World Bank, 1994), http://documents.worldbank.org/ curated/en/627501467990056231/The-World-Bank-and-Participation.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Recommendation of the Council on Open Government” (Paris: OECD, 2017), https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0438.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Strategy on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance (Washington, DC: USAID, June 2013), https://www.usaid.gov/ sites/default/files/documents/1866/USAID-DRG_fina-_6-24- 31.pdf.

- Humphreys, Masters, and Sandbu, “The Role of Leaders in Democratic Deliberations.”

- David Van Reybrouck, Against Elections: The Case for Democracy (New York: The Bodley Head, Seven Stories Press, 2016).

- Hugo Mercier and Hélène Landemore, “Reasoning Is for Arguing: Understanding the Successes and Failures of Deliberation,” Political Psychology 33, no. 2 (April 2012): 243–58; H. Landemore, “Beyond the Fact of Disagreement? The Epistemic Turn in Deliberative Democracy,” Social Epistemology 31, no. 3 (2017): 277–95.

- For a further description of the differences between these approaches, see Z. Bone, J. Crockett, and S. Hodge, “Deliberation Forums: A Pathway for Public Participation,” in R.J. Petheram and R. Johnson (Eds.), Practice Change for Sustainable Communities: Exploring Footprints, Pathways and Possibilities (Beechworth, Australia: The Regional Institute Ltd., 2006), https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/ en/publications/deliberation-forums-a-pathway-for-publicparticipation, 1–16; Jon Elster (Ed.), Deliberative Democracy (Columbia University, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Catching the Deliberative Wave: Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,

Catching the Deliberative Wave. - Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Catching the Deliberative Wave.

- Nellie Peyton, “West African Urban Polls Find Clean Water Top Priority,” Reuters, March 17, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-westafrica-resilience-environment-watidUSKBN16O1OZ.

- Paul Rothman, The Politics of Media Development: The Importance of Engaging Government and Civil Society (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, September 2015), https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/CIMA-The-Politics-of-Media-Development. pdf.

- Ibid.

- Gallup, “World Poll,” 2018, https://www.gallup.com/topic/world_poll.aspx.

- Edelman Trust Barometer, 2019 Edelman Trust Barometer

Global Report, 2019, https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2019-02/2019_Edelman_Trust_Barometer_Global_Report.pdf. - Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust, OECD Public Governance Reviews (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en.

- CIVICUS, People Power under Attack: A Global Analysis of Threats to Fundamental Freedoms, November 2018, https://www.civicus.org/documents/PeoplePowerUnderAttack. Report.27November.pdf.

- E. Ugarriza and D. Caluwaerts (Eds.), Democratic Deliberation in Deeply Divided Societies: From Conflict to Common Ground (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Catching the Deliberative Wave.

- Author interview with Abadir Ibrahim, Head of Secretariat, Legal and Justice Affairs Advisory Council, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, May 27, 2020.

- Mark Nelson, “What Is to Be Done? Options for Combating the Menace of Media Capture,” in Anya Schiffrin (Ed.), In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017), ISBN 978-0-9818254-2-7.

- Center for Deliberative Democracy, “What Is Deliberative Polling?” https://cdd.stanford.edu/what-is-deliberativepolling/, accessed April 15, 2020.

- Dennis Chirawurah, James Fishkin, Niagia Santuah, Alice Siu, Ayaga Bawah, Gordana Kranjac-Berisavljevic, and Kathleen Giles, “Deliberation for Development: Ghana’s First Deliberative Poll,” Journal of Public Deliberation 15, no. 1 (2019), http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.314.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Southern Africa Resilience Innovation Lab, “Gauging Citizens’ Voice: Strengthening Resilience in Nsanje District, Southern Malawi,” Presentation, via Stanford Center for Deliberative Democracy, October 2017, https://cdd.stanford.edu/2017/gauging-citizens-voice-strengthening-resilience-in-nsanjedistrict-southern-malawi/.

- Beatriz Magaloni, Alberto Díaz-Cayeros, and Alexander Ruiz Euler, “Public Good Provision and Traditional Governance in Indigenous Communities in Oaxaca, Mexico,” Comparative Political Studies, CPS-17-0217.R2, August 30, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Chirawurah, Fishkin, Santuah, Siu, Bawah, Kranjac- Berisavljevic, and Giles, “Deliberation for Development: Ghana’s First Deliberative Poll.”

- Nelson, “What Is to Be Done? Options for Combating the Menace of Media Capture.”

- Jefferson Center, “Your Voice Ohio,” https://jefferson-center.org/your-voice-ohio/, accessed April 2, 2020.”

- Jefferson Center, “Your Voice Ohio.”

- Jefferson Center, “Informed Citizen Akron & Your Vote Ohio,” https://jefferson-center.org/ic-akron/, accessed April 15, 2020.

- The World Café, website, http://www.theworldcafe.com, accessed April 20, 2020; for a discussion of various models, see Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Catching the Deliberative Wave.

- Jefferson Center, “Your Voice Ohio.”

- Ibid.

- Jefferson Center, “Informed Citizen Akron & Your Vote Ohio.”

- Jefferson Center, “Your Voice Ohio.”

- Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue (Eds.), Democracies Divided: The Global Challenge of Political Polarization (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2019).

- Bobby Duffy, The Perils of Perception: Why We Are Wrong about Nearly Everything (London: Atlantic Books, 2018).

- Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts, Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), ISBN: 0190923628.

- Simone Chambers, “Truth, Deliberative Democracy, and the Virtues of Accuracy: Is Fake News Destroying the Public Sphere?” Political Studies, April 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719890811.

- Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakshan, Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making, Council of Europe report, DGI(2017)09, 2017.

- Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral, “The Spread of True and False News Online,” Science 359, no. 6380 (March 9, 2018): 1146–51, DOI: 10.1126/science.aap9559.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Governance Responses to Disinformation: How Open Government Principles Can Help Tackle Disinformation, Promote Dialogue and Increase Trust (Paris: OECD Publishing, forthcoming).

- Jane Suiter, “Deliberation in Action: Ireland’s Abortion Referendum,” Political Insight 9, no. 3 (2018): 30–32, https://doi.org/10.1177/2041905818796576/.

- The Citizens’ Assembly, website, https://www.citizensassembly.ie/en/, accessed April 20, 2020.

- Author interview with Jane Suiter, Director, Institute for Future Media and Journalism, April 6, 2020.

- J.S. Dryzek, A. Bächtiger, S. Chambers, J. Cohen, J.N. Druckman, A. Felicetti, J.S. Fishkin, et al., “The Crisis of Democracy and the Science of Deliberation,” Science 363, no. 6432 (2019): 1144–46, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2694; Kimmo Grönlund, Kaisa Herne, and Maija Setälä, “Does Enclave Deliberation Polarize Opinions?” Political Behavior 37, no. 995 (2015), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11109-015-9304-x; Mercier and Landemore, “Reasoning Is for Arguing.”

- Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti, Fishkin, et al., “The Crisis of Democracy and the Science of Deliberation”; Grönlund, Herne, and Setälä, “Does Enclave Deliberation Polarize Opinions?”

- David Farrell and Jane Suiter, Reimagining Democracy: Lessons in Deliberative Democracy from the Irish Front Line (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2019); Author interview with Jane Suiter, Director, Institute for Future Media and Journalism, April 6, 2020.

- Author interview with Jane Suiter, Director, Institute for Future Media and Journalism, April 6, 2020.

- R.E. Goodin and J.S. Dryzek, “Deliberative Impacts: The Macro-Political Uptake of Mini-Publics,” Politics & Society 34, no. 2 (2006): 219–44, https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329206288152.

- Author interview with Jane Suiter, Director, Institute for Future Media and Journalism, April 6, 2020.

- Suiter, “Deliberation in Action: Ireland’s Abortion Referendum.”

- J.S. Fishkin, When the People Speak: Deliberative Democracy and Public Consultation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); J. Gastil, “Adult Civic Education through the National Issues Forums: Developing Democratic Habits and Dispositions through Public Deliberation,” Adult Education Quarterly 54 (2004): 308–28; M.E. Morrell, “Deliberation, Democratic Decision Making and Internal Political Efficacy,” Political Behavior 27 (2050): 49–69, as cited in K.R. Knobloch, M.L. Barthel, and J. Gastil, “Emanating Effects: The Impact of the Oregon Citizens’ Initiative Review on Voters’ Political Efficacy,” Political Studies (2019), https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719852254.

- Knobloch, Barthel, and Gastil, “Emanating Effects: The Impact of the Oregon Citizens’ Initiative Review on Voters’ Political Efficacy.”

- R.G. Niemi, S.C. Craig, and F. Mattei, “Measuring Internal Political Efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study,” American Political Science Review 85 (1991): 1407–13, see Figure 4.

- Knobloch, Barthel, and Gastil, “Emanating Effects: The Impact of the Oregon Citizens’ Initiative Review on Voters’ Political Efficacy.”

- Healthy Democracy, “Citizens’ Initiative Review,” https://healthydemocracy.org/cir/, accessed April 15, 2020.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Catching the Deliberative Wave.

- Healthy Democracy, “Citizens’ Initiative Review.”

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Catching the Deliberative Wave.

- Healthy Democracy, “Citizens’ Initiative Review.”

- Knobloch, Barthel, and Gastil, “Emanating Effects: The Impact of the Oregon Citizens’ Initiative Review on Voters’ Political Efficacy.”

- Ibid.

- ResilientAfrica Network (2017), “Senegal Deliberative Poll Preliminary Results,” March 3, 2017, https://cdd.stanford.edu/2017/senegal-deliberative-poll-preliminary-results/.

- Peyton, “West African Urban Polls Find Clean Water Top Priority.”

- Farrell and Suiter, Reimagining Democracy.

- Southern Africa Resilience Innovation Lab, “Gauging Citizens’ Voice: Strengthening Resilience in Nsanje District, Southern Malawi.”

- Farrell and Suiter, Reimagining Democracy.

- Author interview with Claudia Chwalisz, Policy Analyst, Open Government Unit, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, March 25, 2020.

- Author interview with Abadir Ibrahim, Head of Secretariat, Legal and Justice Affairs Advisory Council, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, May 27, 2020.

- Author interview with Jane Suiter, Director, Institute for Future Media and Journalism, April 6, 2020.

- newDemocracy Foundation, Enabling National Initiatives to Take Democracy Beyond Elections, UN Democracy Fund and the newDemocracy Foundation, 2019, https://www.newdemocracy.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/newDemocracy-UNDEF-Handbook.pdf.

- Author interview with Jane Suiter, Director, Institute for Future Media and Journalism, April 6, 2020.

- Mark Nelson, “A Global Strategy for Combatting Media Capture,” In Anya Schiffrin (Ed.), How Money, Digital Platforms and Governments Control the News (New York: Columbia University Press, Forthcoming).

- Ibid.

- For example, see María Soledad Segura and Silvio Waisbord, Media Movements: Civil Society and Media Policy Reform in Latin America (London: Zed Books, 2016) and Rothman, The Politics of Media Development.

- Mark Nelson, “Redefining Media Development: A Demand Driven Approach,” in Nicholas Benequista, Paul Rothman, Winston Mano, and Susan Abbott (Eds.), International Media Development: Historical Perspectives and New Frontiers (New York: Peter Lang and National Endowment for Democracy, 2019).