Key Findings

In many countries, mobile operators have teamed up with social media platforms to offer free access to specific websites or internet services—including news websites. The most well-known of these offerings, Facebook’s Free Basics, has been explicitly pitched as a way to give citizens in developing countries greater access to news, but Facebook is not the only company touting these so-called “zero-rated” arrangements as a bridge across the digital divide. This report examines whether these arrangements are broadening access to diverse sources of news, as promised, and whether they might have broader consequences for the news market.

• Little evidence exists that zero-rating alone has been a successful strategy to grow audience reach.

• Technical hurdles jeopardize news media inclusion, especially for smaller outlets.

• Zero-rated news is a concern for fair markets and pluralism as it might strengthen the dominance of large internet platforms.

Platforms, Pluralism, and the Debate over Zero-rating News

When mobile phone service providers offer free access to news content, are citizens better informed? Are these bundled offerings a good way for independent news producers to expand their audiences? In developing countries—where access to the internet takes place predominantly through mobile phones and where mobile data can be cost-prohibitive—these questions are especially consequential. As evidence grows about how so-called free internet offerings play out in the real world, we are now gaining a better understanding of their implications for media pluralism.

Mobile network operators have teamed up with social media platforms in several countries to offer free access to specific websites or internet services—including news websites. This practice, which is referred to by the technical term “zero‑rating,” enables customers to download and upload certain online content entirely for free or without having their usage counted against their data limits if they have a mobile plan. Thus, from the consumer’s perspective, access to these sites and services appears to be free because it incurs no direct cost to them.

While the appeal of zero-rating is understandable, countries including Chile and India have rejected these arrangements because they infringe on the principle of net neutrality, which holds that internet service providers—like mobile network operators—should not be able to interfere in terms of what content internet users are able to access. More recently, critics have charged that zero-rating specific platforms may result in an unfair market advantage that is detrimental to open markets and innovation. Indeed, the debate over whether zero-rating serves the public interest is wrapped up in much larger questions regarding how best to govern the outsized role of social media platforms and other internet services companies in contemporary life worldwide. Recent market developments and infrastructure design choices are instead centralizing power over the internet in the hands of large technology firms vying for marketplace supremacy.1 This centralization has given rise to new gatekeepers who mediate what is and what is not accessible online. The examination in this report of how zero-rating intersects with news markets underscores this concern about how companies exercise control over the flow of information in the digital age. Zero-rating gained prominence in the 2010s when Facebook, Google, and the Wikimedia Foundation launched initiatives that enabled consumers in developing countries to access their platforms through specific zero-rated applications.2 The public rationale for Facebook’s Free Basics, Google Free Zone, and Wikipedia Zero was to ameliorate the digital divide by enabling access for low-income consumers to specific internet services that they could not afford. In particular, Facebook has promoted its stand-alone app, Free Basics, as a way for low-income consumers to gain access to news content that otherwise might not be available to them.3 When Free Basics launched in countries, Facebook ensured that at least one local news outlet was included in the app in each country where it was available alongside other public service resources like health and education apps.

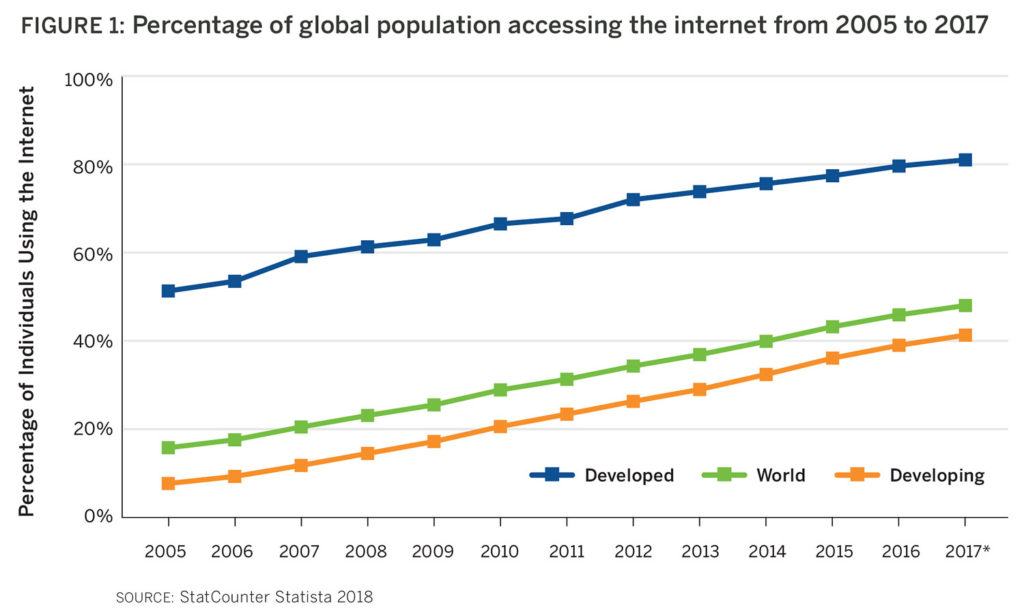

Extending internet access to those who do not yet have access is an important public policy goal. This is especially true given that the internet increasingly serves as an important tool for exercising a whole host of human rights, including the right to access news and information. According to the most recent data from the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), however, less than half of the global population has internet access.4 In developing countries, only 41 percent of individuals have any type of internet access. Thus, while the so-called digital divide is shrinking, billions of people remain unconnected. While extending internet access to these people is an urgent priority, the access they receive must be of sufficient quality to afford them the full opportunities the internet offers.

This report examines one important component of the public interest argument for zero-rating—that it will help get news to users, particularly poorer users. First, we analyze zero-rating by placing it within the context of broader shifts in the digital ecosystem that are the result of market forces. We also examine these offerings in relationship to ongoing discussions about the role of net neutrality policies in securing freedom of expression and access to information online. Then we examine four brief case studies of how zero-rating has impacted the news ecosystem in India, Burma, the Philippines, and Jamaica. We argue that zero rating creates multiple concerns in terms of the lack of transparency, diversity of media sources, and the growing concentration of market power in the hands of a few social media and internet platforms.

This report examines one important component of the public interest argument for zero-rating—that it will help get news to users, particularly poorer users. First, we analyze zero-rating by placing it within the context of broader shifts in the digital ecosystem that are the result of market forces. We also examine these offerings in relationship to ongoing discussions about the role of net neutrality policies in securing freedom of expression and access to information online. Then we examine four brief case studies of how zero-rating has impacted the news ecosystem in India, Burma, the Philippines, and Jamaica. We argue that zero rating creates multiple concerns in terms of the lack of transparency, diversity of media sources, and the growing concentration of market power in the hands of a few social media and internet platforms.

Defining Zero-rating

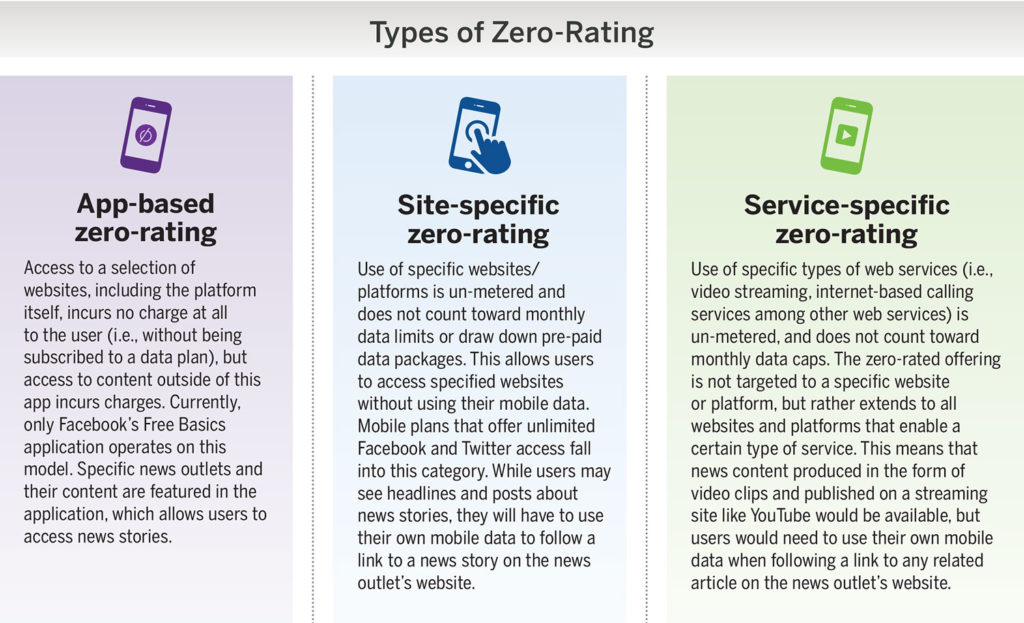

Understanding zero-rating can be somewhat challenging at first. These arrangements can take many forms and often involve multiple partners with different business interests. For example, zero-rating often represents a partnership between a mobile network operator and a social media platform, like Facebook or Twitter. In some cases, other stakeholders, like news outlets, become involved when they are encouraged to provide content for a zero-rated offering, such as Facebook’s Free Basics. For the purposes of this report, we have classified the types of zero-rating based on what it looks like from the user’s perspective, for example, how a mobile phone user might experience these arrangements. This can be described in terms of three types of zero-rating: app-based zero-rating, single-site zero-rating, and single-service zero-rating. By far, the most high-profile example of zero-rating is Facebook’s Free Basics. Free Basics is a mobile application that gives users access to Facebook’s social media platform and a selection of websites—including some news outlets—in a “data-lite” form. Operating in partnership with local mobile networks, Facebook has launched this application in more than 20 countries with low internet penetration. Facebook contends that “by introducing people to the benefits of the internet through these websites, we hope to bring more people online and help improve their lives.”5

While a significant portion of the analysis in this report focuses on zerorating in the form of Free Basics, this is not the sole focus of the report. Rather, the attention given to Free Basics merely reflects the close links between Free Basics and news. Facebook has promoted Free Basics to users as an opportunity to gain access to news and has actively recruited news outlets to participate in the initiative. However, other types of zero-rating also have an impact on both news outlets and news consumers. This is because these arrangements preference certain types of access over others. In this way, the debate over zero-rating is part of a larger conversation about the principles of net neutrality and how it may impact access to information.

While a significant portion of the analysis in this report focuses on zerorating in the form of Free Basics, this is not the sole focus of the report. Rather, the attention given to Free Basics merely reflects the close links between Free Basics and news. Facebook has promoted Free Basics to users as an opportunity to gain access to news and has actively recruited news outlets to participate in the initiative. However, other types of zero-rating also have an impact on both news outlets and news consumers. This is because these arrangements preference certain types of access over others. In this way, the debate over zero-rating is part of a larger conversation about the principles of net neutrality and how it may impact access to information.

Broader Trends Giving Rise to Zero-Rating

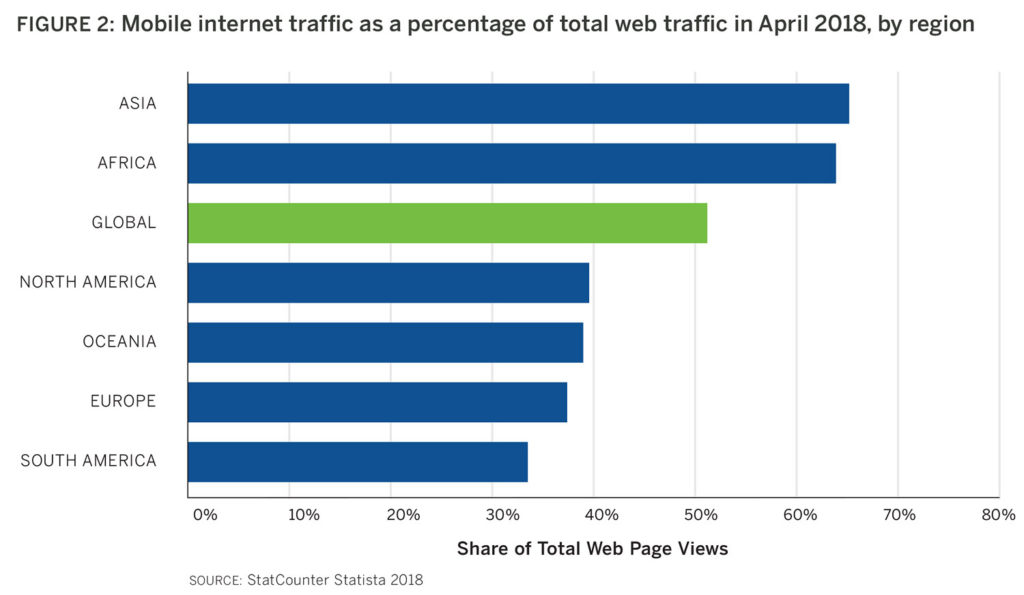

Two global trends are significantly reshaping how individuals access news and information online: the growth of mobile internet and the emergence of dominant tech platforms. The first trend suggests that the future of internet access worldwide will most likely be through mobile networks. Already, for instance, in Asia and Africa, more than two-thirds of internet traffic is through a mobile connection.6 The development of faster mobile and wireless internet standards will probably increase reliance on mobile connections, even in countries where landline broadband penetration is high. This means that policies and management of mobile internet will profoundly impact the type of access people have in the future. Policies that shape the flow of data on mobile networks will increasingly shape how users interact with news and information online.

The second trend relates to what analysts have called the “platformization” of content distribution.7 Increasingly, content producers, including news publishers, are turning to the large social media and messaging platforms to distribute their content. Examples include platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, WhatsApp, and Google. This role in the distribution of news and information gives these platforms a much larger role in influencing what type of content is shown to which people. Moreover, these large platforms have been increasingly called upon to moderate content, often to remove disinformation or hateful content. This is why people argue that these platforms are taking on the role traditionally reserved for news publishers.8 The fact that platforms are concentrated in a small number of firms means that decisions once performed by publishers are now being done by large corporations who, by and large, do not consider themselves news media companies.

Zero-rating arrangements can be conceptualized as a value chain in which different stakeholders derive benefit in different ways. For example, if we analyze just mobile internet’s use for the circulation of news content through zero-rating we see that there are at least four links in this chain. First, mobile network operators benefit by providing a service that appeals to new customers. Second, social media companies gain data about users who use their platforms to access and share content, which can ultimately be transformed into advertising revenue. Third, news outlets are able to disseminate content to their audiences, and eventually monetize this reach in the future either through advertising or subscriptions. And finally, news consumers benefit by accessing news and information that helps them become better informed. Each stakeholder on this value chain is motivated by different factors, and thus has different incentives in how the overall system would ideally operate. By teasing out the motivations of different actors in the creation of the zero-rating value chain, we get a better sense of whether or not this arrangement is ultimately benefitting the public good.

Zero-rating arrangements can be conceptualized as a value chain in which different stakeholders derive benefit in different ways. For example, if we analyze just mobile internet’s use for the circulation of news content through zero-rating we see that there are at least four links in this chain. First, mobile network operators benefit by providing a service that appeals to new customers. Second, social media companies gain data about users who use their platforms to access and share content, which can ultimately be transformed into advertising revenue. Third, news outlets are able to disseminate content to their audiences, and eventually monetize this reach in the future either through advertising or subscriptions. And finally, news consumers benefit by accessing news and information that helps them become better informed. Each stakeholder on this value chain is motivated by different factors, and thus has different incentives in how the overall system would ideally operate. By teasing out the motivations of different actors in the creation of the zero-rating value chain, we get a better sense of whether or not this arrangement is ultimately benefitting the public good.

The growing reliance on mobile internet worldwide and the spread of dominant internet platforms set the stage for zero-rating arrangements in which mobile operators offer free access to certain platforms. In almost all known cases, there is no financial exchange between the mobile operators and organizations such as Facebook, Google, or the Wikimedia Foundation. Rather, the mobile networks benefit by gaining a competitive advantage over competitors by providing a service that appeals to consumers, while the platforms stand to gain new users and data, making them more attractive as advertising platforms. In this sense, zero-rating initiatives can be seen as a marriage of convenience that serves the various interests of actors along the internet value chain.9

Proponents of zero-rating, especially in the form of app-based offerings such as Facebook’s Free Basics, contend that in developing countries these arrangements can serve as an “on ramp” to the internet for those who were previously unconnected. Yet research conducted by the Alliance for Affordable Internet in eight developing countries showed that more than 88 percent of survey respondents had accessed the internet before using a zero-rated offering.10 Moreover, zero-rating was not the only method people used in order to get online: only 4 percent of their survey sample relied exclusively on zero-rating to access internet content. Thus, it is far from clear if zero-rating is achieving even its most basic claim.

Little to no research has focused on how zero-rating impacts news outlets and the circulation of news and information. This report intends to fill this gap by examining the impact on news outlets as well as general consumers.

Zero-Rating and the News Market

One of the stated goals of many zero-rating arrangements in developing countries has been to expand internet access to individuals who might not be able to afford costly mobile data plans. For news outlets with digital distribution mechanisms, this has been viewed as an opportunity to expand news readership and diversify audiences. By including news content in zero-rating packages, either through a dedicated application, such as Facebook’s Free Basics, or by distributing news content on zerorated social media platforms, news outlets also hoped to increase their audiences, potentially even reaching marginalized audiences that had yet to have been reached. For digital-only outlets that do not have other means of distribution such as print or television, this was particularly enticing.

One of the stated goals of many zero-rating arrangements in developing countries has been to expand internet access to individuals who might not be able to afford costly mobile data plans. For news outlets with digital distribution mechanisms, this has been viewed as an opportunity to expand news readership and diversify audiences. By including news content in zero-rating packages, either through a dedicated application, such as Facebook’s Free Basics, or by distributing news content on zerorated social media platforms, news outlets also hoped to increase their audiences, potentially even reaching marginalized audiences that had yet to have been reached. For digital-only outlets that do not have other means of distribution such as print or television, this was particularly enticing.

Yet it is precisely this potential of enhanced reach for only select platforms that is at the root of concern with zero-rating. Since zero-rating packages tend to be curated by large social media platforms and mobile operators, it gives these companies gatekeeping power over who is able to access new audiences. How is this distortion of the news market playing out for news providers and new audiences?

In 2017, Global Voices, a research and advocacy hub, evaluated the Free Basics application in six countries based on usability, quality of connection, language, content, and Facebook’s terms of agreement with content services.11 This research provides rich insights into the actual experience of using the platform. Importantly, the Global Voices researchers compiled a list of all the news media outlets that were available in the countries they studied in-depth: Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, Mexico, Pakistan, and the Philippines. The researchers found that the display of the app is divided into a first page with a selection of sites (what they term “Tier 1”) and the possibility to click “more” to see a comprehensive list of sites (“Tier 2”). The distinction between Tier 1 and Tier 2 services is a crucial one. It illustrates that even within websites and services included in Free Basics, there is a meaningful distinction between the Tier 1 sites favored on the homepage and the Tier 2 services that are not. We borrow this terminology in this report.

When it comes to news offerings on the Free Basics app, the researchers found some cross-cutting trends. The news offerings in Tier 1 were typically split between international sources, such as the BBC and ESPN, and one to three national-level news sites that researchers characterize as being of “varying quality and reputation.”12 Indeed, some of the national-level news services available on Free Basics were merely repackaging or republishing content from other sources rather than publishing original reporting. The Tier 2 offerings included a much wider array of news outlets, though in many cases these did not appear to be relevant for the user. For example, in Mexico, the Tier 2 included international news sites such as Deutsche Welle in Spanish, Voice of America in Spanish, and Buzzfeed News, but also, somewhat peculiarly, TrendyRammy, a Nigerian entertainment news site, and 24/7 News Nigeria, a Nigerian news site. Ultimately, the Global Voices research demonstrates that in curating Free Basics, Facebook did make a concerted attempt to build out a unique, localized news media offering in each country. However, it remained unclear how Facebook decided to prioritize certain types of content over others, or what type of criteria it used in selecting which outlets to include.

When it comes to news offerings on the Free Basics app, the researchers found some cross-cutting trends. The news offerings in Tier 1 were typically split between international sources, such as the BBC and ESPN, and one to three national-level news sites that researchers characterize as being of “varying quality and reputation.”12 Indeed, some of the national-level news services available on Free Basics were merely repackaging or republishing content from other sources rather than publishing original reporting. The Tier 2 offerings included a much wider array of news outlets, though in many cases these did not appear to be relevant for the user. For example, in Mexico, the Tier 2 included international news sites such as Deutsche Welle in Spanish, Voice of America in Spanish, and Buzzfeed News, but also, somewhat peculiarly, TrendyRammy, a Nigerian entertainment news site, and 24/7 News Nigeria, a Nigerian news site. Ultimately, the Global Voices research demonstrates that in curating Free Basics, Facebook did make a concerted attempt to build out a unique, localized news media offering in each country. However, it remained unclear how Facebook decided to prioritize certain types of content over others, or what type of criteria it used in selecting which outlets to include.

This report builds upon the analysis of Global Voices and takes the research a step further. The focus here is not solely on the inclusion of news outlets in Facebook’s Free Basics, but rather the impact on news content in a variety of zero-rated offerings. By examining how news outlets have viewed and engaged with the sometimes-opaque processes determining which news outlets get to broadcast on what is essentially a free-to-air digital channel, the present research suggests even more strongly the adverse impact on news media ecosystems.

Zero-Rating and Net Neutrality

Critics of zero-rating arrangements contend that they are harmful largely because they favor certain web content or platforms over others, and tilt the level playing field that a decentralized internet affords. Under the principle of net neutrality, internet service providers should treat all data on the internet equally and not discriminate or charge differently based on content, site, platform, or application. In other words, net neutrality “is the principle that the company that connects you to the Internet does not get to control what you do on it.”13 Indeed, Chilean regulators rejected proposed zero-rating arrangements because they violated the principles of net neutrality, which is codified into law in the country.

Critics of zero-rating arrangements contend that they are harmful largely because they favor certain web content or platforms over others, and tilt the level playing field that a decentralized internet affords. Under the principle of net neutrality, internet service providers should treat all data on the internet equally and not discriminate or charge differently based on content, site, platform, or application. In other words, net neutrality “is the principle that the company that connects you to the Internet does not get to control what you do on it.”13 Indeed, Chilean regulators rejected proposed zero-rating arrangements because they violated the principles of net neutrality, which is codified into law in the country.

For net neutrality proponents, the principle is an important safeguard for competition, precluding moves by dominant platforms or mobile service providers at the expense of existing competitors and start-ups yet to come.14 The risk, critics of zero-rating allege, is that first-time internet users may get “locked in” to using the dominant platforms given the strong financial disincentive to explore external content.15 New users may not even realize that their internet access is being constrained to a specific subset of the internet, which would thus exclude them from the full range of opportunities the internet offers.16 Likewise, emerging so-called platform monopolists have been charged with undermining traditional regulatory norms that promote a robust free press at the local level as large platforms focus on concentration and efficiency rather than distribution and diversity.17 The fact that these platforms do not have expertise in editorial ethics or practices raises serious questions about their ability to play this public service role.18

For those concerned with press freedom and freedom of expression, net neutrality ensures the creation and flourishing of a news and information environment that produces a diversity of views. In contrast, zero-rating inherently preferences access to certain websites or internet services by making them free of charge, in effect determining which content is available, particularly to lower-income users. Some proponents of zero-rating, however, have been willing to condone its violation of net neutrality principles by pointing to the countervailing benefits of access. This has led to a fierce debate on the topic, with rhetorical flourishes on both sides. “Some internet is better than none” has been met with “this is poor internet for poor people.” These same debates play out in the examples we examine of zero-rating initiatives that have incorporated news content.

India

As a large and quickly developing country, India is one of the biggest markets for both social media companies and mobile networks. The fact that in 2015 the mobile internet penetration rate country-wide was still under 20 percent suggests that the digital divide in the country is still massive. At the same time, India has a sizeable and competitive news media market, which sets it apart from many other developing countries. In 2015, Facebook launched its Internet.org initiative in India—an early precursor to Free Basics. In partnership with the mobile network operator Reliance Communications, Facebook created the Internet.org web application that—when opened while on Reliance’s network—would allow users to navigate to any content within the application. In addition to Facebook’s platform, it also included two dozen other websites that were handpicked by Facebook for inclusion. A pilot rollout took place in Mumbai, one of India’s largest cities.

There was almost immediate pushback from activists, civil society, and technologists who argued that Internet.org was discriminatory against those not included in the offering. Telecom operators and Facebook should not decide which websites were privileged with this enhanced reach, they argued. They also questioned whether this limited access to select web content could be equated with the “internet” at all; would the next billion users to come online be locked-in to this walled garden of preselected web content? The Indian telecom regulator, TRAI, took notice of this brewing debate and began a consultation process that sought the public’s comments on whether zero-rated plans in general should be considered discriminatory and therefore restricted.

In response to intense scrutiny in India, Facebook morphed Internet. org into Free Basics worldwide. The name change might have been a response to the critique that this offering was not “the internet,” but this change was more than just semantic. Unlike Internet.org, where Facebook effectively chose what online services populated the platform through partnerships, Free Basics also allowed other services to apply to participate as long as they met minimal technical standards. Meeting the standards did not guarantee that that they would be included, however.

India had a relatively large number of news media outlets available on Internet.org, a list that grew with the changeover to Free Basics. There was a mix of English and vernacular news sites (including OneIndia, which offered multiple versions covering over 15 Indian languages); international outlets (e.g., BBC News); mainstream dailies with vast print or television presence (e.g., Times of India, Dainik Jagran), and smaller online platforms (e.g., Newsbyte.org, Akhbaar Wala). It is worth noting that the relatively obscure smaller news sites did not appear on the main homepage (Tier 1), but instead on the longer list that appeared on click-through to “more” (Tier 2). Crucially, it was Facebook that unilaterally made this decision.

While several prominent news sites made it to the platform, the news media market in India was crowded, and Facebook excluded some key competitors. In the backlash to Free Basics, news media were a frequent illustration of the discriminatory character of the platform. “If Times of India is on Internet.org, what will One India do?” asked Nikhil Pahwa, journalist and founder of the media outlet MediaNama, querying how Free Basics might affect the dynamic between the largest mass market news outlets such as Times of India and niche media organizations such as OneIndia (OneIndia was eventually included in the Free Basics app). Pahwa, a key figure in the net neutrality movement in India, recalls that during the “#SaveTheInternet” campaign, several sites that were on Free Basics pledged support to the campaign and opted out of the platform. For certain news sites, however, it was a tough choice. As Pahwa stated, “If you left, and your competitor news site didn’t, you were left at a clear disadvantage.”

Yet, some outlets that were included in Free Basics later withdrew and publicly pledged support to the anti-zero-rating campaign. A media outlet taking a public stance on a policy issue of this nature is unusual in India—and more so given that the media houses were opposing a policy that could benefit them. Among the companies that withdrew was the Times Internet, which did so in solidarity with its competitors that were not included. It urged its competitors that had been included in Free Basics to withdraw as well, noting on its corporate blog:

Our group commits to withdraw from internet.org if its direct competitors—India Today, NDTV, IBNLive, NewsHunt, and BBC— also pull out. The group also encourages its fellow language and English news publishers—Dainik Jagran, Aaj Tak, Amar Ujala, Maalai Malar, Reuters, and Cricinfo—to join the campaign for net neutrality and withdraw from zero rate schemes.19

It was the current and future threat to competitive market dynamics that explained why news outlets themselves took a stand against zero-rating. In the broader public discourse on the issue, justifications emerged that were more political in nature. News media examples were frequently put forth as a hypothetical of how Free Basics could be manipulated or co-opted by governments or other political actors. The “weaponization” of social media by political actors is now a common refrain in the context of targeted propaganda and political ads, but Free Basics posed a related question. What if the mobile networks or Facebook partnered with governments or political campaign sites to make them available for free? Privileged access to a large demographic of voters, yet to come online, could be a valuable tool in the hands of political agents. Beyond partnerships though, Free Basics is ostensibly open to sites that fulfill technical criteria, which raises another set of questions. In the absence of explicit and transparent criteria governing which sites get included and which excluded, there is little to guard against misinformation campaigns or hateful propaganda finding their ways onto zero-rated platforms. As Nikhil Pahwa argues, eventually such a substantive policy would become inevitable, and Facebook needs to answer the tricky question of whether certain types of news organizations could be banned from the service irrespective of whether they meet the technical criteria. “Then again, we will see the inevitable gatekeeper function kick in,” he noted.

On February 11, 2016, Facebook withdrew the Free Basics platform from India after TRAI determined that zero-rating violated net neutrality, and thus would not be permitted in India. Eventually, the regulator explicitly supported the notion that free speech requires a diversity of information sources: “The Authority is of the view that use of internet should be in such a manner that it advances the free speech rights of the citizens, by ensuring plurality and diversity of views, opinions, and ideas.” The Indian experience continues to hold lessons for how a negative impact on media plurality can and did become a factor against which to evaluate, and eventually decide against, zero-rated plans.

Burma

In the last five years, Burma has seen tectonic shifts in both its economy and politics: a transition from authoritarian military rule towards more democratic governance, as well as a gradual liberalization of various sectors of the economy. In 2011, strict media laws were lifted that had required outlets to obtain a license from the military government. As a consequence, news organizations began to operate more freely, and new independent media outlets appeared. The telecommunications sector was also opened up in 2013, and mobile penetration surged from 7 percent in 2012 to 90 percent in 2016. And while only half of all mobile phones were using data services in 2016, almost 80 percent of individuals owned internet-enabled smartphones.20 This indicated that paying for data services was an impediment to many users. Burma seemed to have the ideal conditions for mobile operators and content platforms to facilitate internet access through zero-rating.

Facebook launched Free Basics in June 2016 in partnership with stateowned mobile carrier Myanmar Post and Telecommunications (MPT). In Burma, the Free Basics app provided access to a video-free version of Facebook and Facebook Messenger, Burmese Wikipedia, resources from UNICEF’s Internet of Good Things, and a handful of other public interest sites. The only news portal on Free Basics was 7Day Daily, an independent news outlet with a strong online presence, particularly in terms of Facebook followers.

Given the blossoming of news media in the country and the growing diversity of offerings, having only one news outlet available on the application was notable and generated a great deal of speculation and concern as to why. The general manager of 7Day Daily, Stanley Myo Hlaing Aung, indicated in an interview that 7Day Daily was approached by Facebook for inclusion and that “several other outlets were approached too, but it didn’t work out.” He said that the other news organizations did not possess the “technical expertise” necessary to be able to maintain a lite version of their content that was compatible with the Free Basics app. At the time of the launch, other news media companies would have had to “build this digital capacity just to service Free Basics.”

7Day Daily did see a slight bump in readership from access through Free Basics, which may have been related to the fact that MPT heavily promoted the app in its advertising. However, even with the Free Basics app available in the Burma market, 80 percent of referrals to 7Day Daily’s website were still coming directly from the regular Facebook platform, rather than from traffic generated through the zero-rated Free Basics app. Indeed, Facebook, as a social media platform, has been incredibly popular in Burma. Htaike Htaike Aung, a Burmese internet activist, said that she considered Free Basics to have been a limited success. In her opinion, the absence of video content and highresolution video made it less attractive to new users, who were much more interested in accessing the regular Facebook platform.

In September 2017, Free Basics was withdrawn from the market in Burma. According to news reports, the government and state-owned MPT decided to end programs that provided free access to data on the basis that they were discriminatory.21 Coincidentally, this was around the same time that Facebook first took flack for not adequately dealing with hate speech that went viral in the country, which ultimately prompted an open letter from Burmese civil society22 and then a direct response from Mark Zuckerberg himself.23 While the company clarified that removing Free Basics was unrelated to this issue, it does suggest that in highly volatile political and social contexts the introduction of new internet services can have unintended consequences, and are also being met with more scrutiny from governments and civil societies.

Philippines

When Facebook launched Free Basics in the Philippines in 2015, the online news site Rappler was one of the first news organizations to sign up to participate. In many ways this seemed like an obvious choice for the relatively new digital outlet. In fact, the rise of Rappler was linked to the spread of social media, particularly Facebook, in the Philippines. Rappler’s genesis can be traced to Move.PH, a Facebook page started in August 2011 to harness the power of social media to share news and information that could help citizens hold public and private actors to account. This morphed into a full-fledged online news site in January 2012. The objective was to use the power of social media to increase access to hard-hitting independent news. So participating in Free Basics made sense if it could help the news outlet reach a wider audience. As Maria Ressa, the co-founder and CEO of Rappler, said in a promotional video produced by Facebook, “Free Basics gives us a way to talk to people who wouldn’t normally have access to Rappler.”24 Given that Rappler’s model is predicated on developing audience engagement to help shape news coverage, this opportunity was perhaps even more exciting to Rappler than to other news outlets. The Philippines, too, provided a propitious environment; the average internet user there spends more than four hours on social media each day.

When Free Basics launched in the Philippines, it actually had a robust offering of national news outlets in both Tier 1 and Tier 2 that, in addition to Rappler, included the Philippine Star, the Daily Inquirer, and the SunStar.25 More than any of its competitor, however, Rappler invested in making Free Basics a central platform. In addition to meeting the basic requirement of creating a data-lite version of its stories for Free Basics, Rappler went further by actively promoting the use of Free Basics among its audience. Rappler staff held capacity-building workshops in poorer communities where the use of zero-rated internet access was most likely to take off. By showing individuals how to use the zero-rated offering, Rappler hoped to expand its audience and develop new forms of civic engagement in marginalized communities.

In spite of these efforts, Free Basics turned out to be a less effective channel for reaching new audiences than Rappler had hoped. According to Gemma Mendoza, Rappler’s head of research and content strategy, there were very few people who were reading full Rappler stories through Free Basics. The experiment was also a letdown in terms of its impact on traffic to the Rappler website. Mendoza believes that the disappointing results emanated from the suboptimal experience of the lite version on Free Basics. Rappler had invested heavily in multimedia content that was popular with social media audiences. Stripped of its most engaging content for a zero-rated platform, Rappler may have lost its appeal.

Even though mobile users were not accessing Rappler in great numbers through Free Basics, they were taking advantage of other site-specific zero-rating arrangements offered by mobile operators that provided free access to Facebook. That is, users were accessing the Facebook platform on their phones and were seeing Rappler content that had been shared there. Indeed, according to Mendoza, up until 2017 Facebook was still the largest referrer to Rappler. However, this site-specific zero-rating causes another issue when it comes to consuming news media. Mobile users on Facebook are able to view the headlines of Rappler stories that are shared, but in order to click through to the entire article or video, they must use their mobile data. For those with data, this means that they will incur a cost to read the article. For those without data, clicking through is simply impossible. This leads to a scenario where people are likely to read the headline, but not the full story and the deeper context. For Rappler, this type of access greatly diminishes its ability to help inform the broader public. Even more alarming is that this type of limited Facebook-only access has been linked to the viral spread of disinformation in the Philippines. Misleading click-bait headlines have been weaponized by political actors to spread disinformation through Facebook.26 Even if individuals wanted to investigate a certain claim they saw on social media, the zero-rating arrangement creates a barrier for users without data—they are able to see only what is accessible through Facebook.

Even though mobile users were not accessing Rappler in great numbers through Free Basics, they were taking advantage of other site-specific zero-rating arrangements offered by mobile operators that provided free access to Facebook. That is, users were accessing the Facebook platform on their phones and were seeing Rappler content that had been shared there. Indeed, according to Mendoza, up until 2017 Facebook was still the largest referrer to Rappler. However, this site-specific zero-rating causes another issue when it comes to consuming news media. Mobile users on Facebook are able to view the headlines of Rappler stories that are shared, but in order to click through to the entire article or video, they must use their mobile data. For those with data, this means that they will incur a cost to read the article. For those without data, clicking through is simply impossible. This leads to a scenario where people are likely to read the headline, but not the full story and the deeper context. For Rappler, this type of access greatly diminishes its ability to help inform the broader public. Even more alarming is that this type of limited Facebook-only access has been linked to the viral spread of disinformation in the Philippines. Misleading click-bait headlines have been weaponized by political actors to spread disinformation through Facebook.26 Even if individuals wanted to investigate a certain claim they saw on social media, the zero-rating arrangement creates a barrier for users without data—they are able to see only what is accessible through Facebook.

Ultimately, Free Basics did not advance Rappler’s aim of extending access to news to marginalized communities. Moreover, some now wonder whether zero-rating and the prominence of Facebook as a platform is creating an environment where low-quality content and even misinformation can proliferate.

Jamaica

To date, the vast majority of zero-rating arrangements have been devised and implemented by private entities. In effect, these private interests play an outsized role in shaping the type of access consumers enjoy in zero-rated offerings. Entirely different concerns emerge when a government is actively engaged in developing such an arrangement. On the one hand, extending internet access is a legitimate government interest. On the other, prioritizing certain types of content, particularly news and information, could easily slip into forms of censorship. This is a primary concern for critics of zero-rating who contend that the centralization of information gatekeepers will enable governments to exert increased pressure on the news and information ecosystem. Some have even gone so far as to argue that zero-rating is a “dictator’s dream” because of how it might enable regimes to help shape what content is available to citizens.27 The fears of government-controlled or influenced zero-rating have not come to pass so far. Indeed, during the course of our research we encountered no clear-cut example of a government using a zero-rating arrangement to try to influence the public sphere. However, a unique agreement in Jamaica did demonstrate government interest in the potential of zero-rating arrangements to give citizens access to pertinent news and information.

In June 2016, the government of Jamaica signed a memorandum of agreement with the country’s two largest mobile networks, Digicel and Flow, that effectively zero-rates all government websites.28 This means that citizens are always able to access government content on their mobile phones even if they are unable to pay for data. Included in the over 250 government websites that are zero-rated is the Jamaica Information Service (JIS) news portal, whose mission is to inform the public about the policies, programs, and activities of the Jamaican government.29 According to a 2017 press release from Digicel, the program has been successful.30 Yet, there is little evidence that this arrangement has been developed in a way to particularly benefit distribution of news content from JIS. There is no promotion on the JIS website stating that its content is available for free in Jamaica through mobile devices. Perhaps more tellingly, in response to our questions, JIS stated that it is unable to tell whether viewers of its content are accessing it through this arrangement. Thus, while zerorating arrangements could be developed by governments as a way to promote the government line, in Jamaica there appears to be little evidence of harmful government intervention that would distort the news media ecosystem.

Conclusion

Fostering a more robust and pluralistic news media ecosystem is one of the most pressing issues of our time. Yet, while zero-rating might make parts of the internet available to more people, it may also create distortions in the world’s news and information ecosystem that deserve further scrutiny. By favoring certain web content or platforms over others and tilting the level playing field that a decentralized internet affords, zero-rating may not be the panacea to resolving the digital divide that some had hoped. Indeed, examining zero-rating from the perspective of the news media ecosystem, as we have done here, suggests that these arrangements, at least as they are currently conducted, may not be significantly improving access to news and diverse sources of information.

Fostering a more robust and pluralistic news media ecosystem is one of the most pressing issues of our time. Yet, while zero-rating might make parts of the internet available to more people, it may also create distortions in the world’s news and information ecosystem that deserve further scrutiny. By favoring certain web content or platforms over others and tilting the level playing field that a decentralized internet affords, zero-rating may not be the panacea to resolving the digital divide that some had hoped. Indeed, examining zero-rating from the perspective of the news media ecosystem, as we have done here, suggests that these arrangements, at least as they are currently conducted, may not be significantly improving access to news and diverse sources of information.

The backlash against Facebook’s Free Basics app in India also included a concern over whether zero-rating would effectively limit the type of information available to citizens. Since only a select group of news services were initially included in the offering, Facebook faced accusations that its preferential treatment could skew the news media market. We even saw large news conglomerate Times Internet withdrawing from Free Basics and urging its competitors to do the same. Four important findings emerge from the present research that suggest that some of the arguments for zero-rating need to be reexamined.

1. Little evidence exists that zero-rating alone has been a successful strategy to grow audience reach: While zero-rated offerings, and in particular app-based offerings like Free Basics, have been touted as a way for citizens to access news, the news outlets contacted for this report have not found these arrangements to significantly increase their audience reach. For example, early proponents of Free Basics, like Rappler in the Philippines, noted that very little traffic to their news stories was generated through the Free Basics platform. In Burma, 7Day Daily did see a slight uptick in access, but it was dwarfed by those accessing it through the regular Facebook platform. In Jamaica, where the Jamaica Information Service news portal is accessible through a site-specific zero-rating arrangement with the nation’s largest mobile networks, the outlet is not actively promoting this access to citizens. Additionally, JIS does not have access to analytics that would enable it to track audience reach through zero-rating, which is information that news outlets can use to evaluate their success and better target their content. Thus, while creating access to news may be listed as one of the rationales for these offerings, there appears to be little evidence that they are truly extending access to new news consumers.

2. Technical hurdles jeopardize news media inclusion: When news outlets are required to alter their content to meet zero-rated platform requirements, this presents a technical barrier that can be hard for many news organizations to overcome. In particular, smaller independent news organizations that are not tech savvy may not be able to participate, making the offerings less diverse than what is available on the internet. For example, in Burma, only 7Day Daily was included in the initial Free Basics offering, not because it was the only outlet approached by Facebook, but because others did not have the resources to create the “data-lite” versions of their content to participate. Even large news outlets with tech teams must make decisions about how to best use their resources, which can be challenging at a time when news organizations are struggling to sustain themselves. This effectively limits the diversity of news offerings consumers have access to through zero-rating. In this way, zero-rating arrangements appear to benefit larger, more-dominant news outlets at the expense of others.

3. Zero-rating may exacerbate the spread of disinformation: Those interviewed for this report, though most notably in the Philippines, expressed concern that zero-rating may help spread disinformation online. This might occur when users read the sensational headlines of news stories, but do not click through to read the full context of the article to avoid a data charge. Moreover, since zero-rating does not provide full access to the internet, users are prevented from further investigating a story on their own to determine its accuracy or veracity. While more research could be done to examine the spread of disinformation on zero-rated platforms, these concerns cast further doubt on the claim that zero-rating fosters a more informed citizenry.

4. Zero-rated news is a concern for fair markets and pluralism: If zero-rating effectively strengthens the market dominance of large platforms by helping them lock-in new consumers in developing markets, as its critics suggest, this may have long-term, detrimental impacts on pluralistic news ecosystems. Specifically, it may speed up the platformization of news in these countries.31 Given that the digital ad market is dominated worldwide by Google and Facebook, this may put news organizations at a further disadvantage.32 In short, if zerorating strengthens the firms that have captured the digital advertising market, this may further jeopardize the ability of news outlets to chart their own destinies online.

In terms of innovative solutions to connecting the unconnected, it is important to remember that zero-rating represents just one of the potential models for expanding access to news and information online. Indeed, there are other viable options that should be considered by mobile operators, social media companies, and government regulators. One alternative would be to zero-rate all internet data at 2G speeds. In essence this would provide users access to the entire internet, albeit at much reduced speeds. This would potentially entice content producers to create sites accessible to users with low data speeds. Another option is referred to as equal rating, which entails giving mobile users a limited about of data to consume—without restricting the type of data or websites the free data could count toward—in return for watching an advertisement. This would “enable access to the ‘full internet’ on a limited basis, and also provide a subsidy (for those willing to watch advertisements), and therefore should address most of the concerns of net neutrality advocates” about internet service providers limiting what content is easily available.33 Moreover, these approaches to expanding access would not run the risk of exacerbating the dominance of certain platforms since users would not be constrained to accessing material through specific content providers.

In terms of innovative solutions to connecting the unconnected, it is important to remember that zero-rating represents just one of the potential models for expanding access to news and information online. Indeed, there are other viable options that should be considered by mobile operators, social media companies, and government regulators. One alternative would be to zero-rate all internet data at 2G speeds. In essence this would provide users access to the entire internet, albeit at much reduced speeds. This would potentially entice content producers to create sites accessible to users with low data speeds. Another option is referred to as equal rating, which entails giving mobile users a limited about of data to consume—without restricting the type of data or websites the free data could count toward—in return for watching an advertisement. This would “enable access to the ‘full internet’ on a limited basis, and also provide a subsidy (for those willing to watch advertisements), and therefore should address most of the concerns of net neutrality advocates” about internet service providers limiting what content is easily available.33 Moreover, these approaches to expanding access would not run the risk of exacerbating the dominance of certain platforms since users would not be constrained to accessing material through specific content providers.

The global debate concerning the benefits of zero-rating is far from settled. While some countries have banned it entirely, in other place it remains a staple of mobile network offerings. What this research demonstrates is that zero-rating has the potential to distort the news market in ways that can be detrimental to pluralism and, in particular, to smaller upstart news producers. It also impacts and might enhance the broader anxiety about how the platformization of news is affecting diversity. As regulators consider the advantages and disadvantages of these strategies to connect the unconnected, particularly in developing countries, the impact on news media plurality must be taken into account.

Footnotes

- Yochai Benkler, “Degrees of Freedom, Dimensions of Power,” Daedalus 145, no. 1 (January 2016): 18, https://doi.org/10.1162/ DAED_a_00362; Matthew Hindman, The Internet Trap: How the Digital Economy Builds Monopolies and Undermines Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

- Samantha Bates, Christopher Bavitz, and Kira Hessekiel, “Zero Rating & Internet Adoption: The Role of Telcos, ISPs & Technology Companies in Expanding Global Internet Access: Workshop Paper & Research Agenda” (Cambridge: Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, October 2017), 1, http://cyber.harvard.edu/ publications/2017/10/zerorating.

- “Connecting the World,” Internet.org, Accessed September 7, 2018, https://info.internet.org/en/.

- “Global Internet Penetration 2017 | Statistics,” Statista, accessed October 22, 2018, https://www.statista.com/statistics/209096/ share-of-internet-users-in-the-total-world-population-since-2006/.

- “Free Basics by Facebook,” Internet.org, August 25, 2015, https:// info.internet.org/en/story/free-basics-from-internet-org/.

- “Share of Mobile Internet Traffic in Global Regions 2018,” Statista, accessed October 18, 2018, https://www.statista.com/ statistics/306528/share-of-mobile-internet-traffic-in-globalregions/.

- Emily Bell and Taylor Owen, “The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley Reengineered Journalism” (New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism, March 27, 2017), https://www.cjr.org/tow_ center_reports/platform-press-how-silicon-valley-reengineeredjournalism.php/.

- Bell and Owen, “The Platform Press.”

- John Walubengo, Kweku Koranteng, and Fola Odufuwa, “Much Ado about Nothing? Zero-Rating in the African Context” (Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, September 12, 2016), 13, https://www.academia.edu/33054644/MUCH_ADO_ ABOUT_NOTHING_ZERO-RATING_IN_THE_AFRICAN_CONTEXT.

- Alliance for Affordable Internet, “The Impacts of Emerging Mobile Data Services in Developing Countries,” Mobile Data Services: Exploring User Experiences and Perceived Benefits (Washington: Alliance for Affordable Internet, June 2016), http://1e8q3q16v yc81g8l3h3md6q5f5e-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/ uploads/2016/05/MeasuringImpactsofMobileDataServices_ ResearchBrief2.pdf.

- Global Voices, “Free Basics in Real Life: Six Case Studies on Facebook’s Internet ‘On Ramp’ Initiative from Africa, Asia and Latin America” (Global Voices, July 27, 2017), https:// advox.globalvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ FreeBasicsinRealLife_FINALJuly27.pdf.

- Global Voices, “Free Basics in Real Life,” 20.

- Carolina Rossini and Taylor Moore, “Exploring Zero-Rating Challenges: Views from Five Countries” (Washington: Public Knowledge, July 2015), https://www.publicknowledge.org/ documents/exploring-zero-rating-challenges-views-from-fivecountries.

- Barbara van Schewick, Internet Architecture and Innovation (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2012).

- Susan Crawford, “Zero for Conduct,” Backchannel (blog), January 7, 2015, https://medium.com/backchannel/less-than-zero199bcb05a868.

- Luca Belli, “Net Neutrality, Zero Rating and the Minitelisation of the Internet,” Journal of Cyber Policy 2 (2016).

- Open Markets Institute, “America’s Free Press and Monopoly” (Washington: Open Markets Institute, 2018), 25, https:// openmarketsinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/ Americas-Free-Press-and-Monopoly-PDF-1.pdf.

- Bell and Owen, “The Platform Press.”

- “Big Win: Times Group Commits to Withdraw from Facebook’s Internet.Org Initiative,” Inc42 Media, April 15, 2015, https://inc42. com/buzz/big-win-times-group-commits-to-withdraw-fromfacebooks-internet-org-initiative.

- Peter Cihon and Helani Galpaya, “Navigating the Walled Garden: Free and Subsidized Data Use in Myanmar” (Colombia, Sri Lanka: LIRNEasia, March 2017), https://lirneasia.net/ wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NavigatingTheWalledGarden_ CihonGalpaya_2017.pdf.

- Manish Singh, “After Harsh Criticism, Facebook Quietly Pulls Services from Developing Countries,” The Outline, May 1, 2018, https://theoutline.com/post/4383/facebook-quietly-ended-freebasics-in-myanmar-and-other-countries.

- Burmese Civil Society, “Open Letter to Mark Zuckerberg,” April 5, 2018, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Rs02G96Y9w5dpX0Vf1LjW p6B9mp32VY-/view.

- Ryan Mac, “Mark Zuckerbeg Sent an Apology Letter about Myanmar. These NGOs Called It ‘Grossly Insufficient.,’” BuzzFeed News, April 9, 2018, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ ryanmac/mark-zuckerbeg-apology-myanmar-ngos-insufficient.

- Internet.org, “Free Basics Content Partner: Rappler, Philippines,” YouTube, July 17, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=x5gJmxa1fxY.

- Global Voices, “Free Basics in Real Life,” 21.

- Davey Alba, “Duterte’s Drug War and the Human Cost of Facebook’s Rise in the Philippines,” BuzzFeed News, September 4, 2018, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/daveyalba/ facebook-philippines-dutertes-drug-war.

- Nanjala Nyabola, “Facebook’s Free Basics Is an African Dictator’s Dream,” Foreign Policy (blog), October 27, 2016, https:// foreignpolicy.com/2016/10/27/facebooks-plan-to-wire-africa-is-adictators-dream-come-true-free-basics-internet/.

- “MoA between Government, Digicel and Flow on Zero-Rated Access for All Government Websites,” Ministry of Science Energy & Technology, accessed October 18, 2018, https://www.mset.gov. jm/moa-between-government-digicel-and-flow-zero-rated-accessall-government-websites.

- “Jamaica Information Service News,” Jamaica Information Services News, Homepage, accessed October 18, 2018, https://jis. gov.jm/.

- “Digicel Records High Traffic on Free GOJ Websites,” Digicel, accessed October 18, 2018, https://www.digicelgroup.com/jm/en/ mobile/explore/other-stuff/news—community/2017/march/16/ digicel-records-high-traffic-on-free-goj-websites.html.

- Bell and Owen, “The Platform Press.”

- Michelle Foster, “Media Feast, News Famine: Ten Global Advertising Trends That Threaten Independent Journalism” (Washington: Center for International Media Assistance, January 5, 2017), https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ CIMA-Media-Feast-News-Famine_REV_web150ppi.pdf.

- Helani Galpaya, “Zero Rating in Emerging Economies” (Centre for International Governance Innovation, February 2017), 13–14, https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/ GCIG%20no.47_1.pdf.