Key Findings

The future of independent journalism is in crisis. Escalating threats are driving a record number of journalists into exile and authoritarians are finding new ways to silence journalism, control the information space, and stifle public debate and dissent. Traditional business models for the media are no longer viable in the wake of digital transformations. To secure the future of independent journalism, international aid is critical. And yet, the international assistance community is not meeting the needs of a sector in danger of extinction. Support for media has languished at 0.3 percent of total official development assistance. Out of the more than $200 billion of development aid spent each year, just $317 million on average is committed to support media freedom, pluralism, and independence. While the world’s major democracies have reaffirmed their commitment to saving independent media in recent years, this has yet to translate into a meaningful increase in foreign assistance to the sector.

– In the face of new crises, like the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, donors have come out with strong policy statements affirming the need for quality independent media. Yet few have announced corresponding increases in aid to support media.

– Six donors provide the lion’s share of foreign aid to media development, but they are also the countries that provide the largest amount of official development assistance overall. Few new countries have answered the siren call and added media development as a priority area for international assistance.

– Most development agencies are not equipped with the technical expertise to address the sector’s thorniest challenges, including how to improve financial sustainability, build political will for media freedom and independence, and promote local ownership of media development.

Introduction

Independent media are in crisis in countries around the world, with 2022 marking a more than 10-year decline in media freedom and independence globally.1 The sector is increasingly throttled by deepening polarization, widespread democratic recessions, and new technologies and legal tactics that are being used to undermine a free press. Independent journalism is also in financial peril. As production and consumption have moved online, media outlets have lost upwards of 60 percent of their advertising revenues to tech platforms.2 This precipitous loss of revenues has made independent media more vulnerable to economic capture by political actors and economic elites who aim to control the public narrative or censor the news industry.

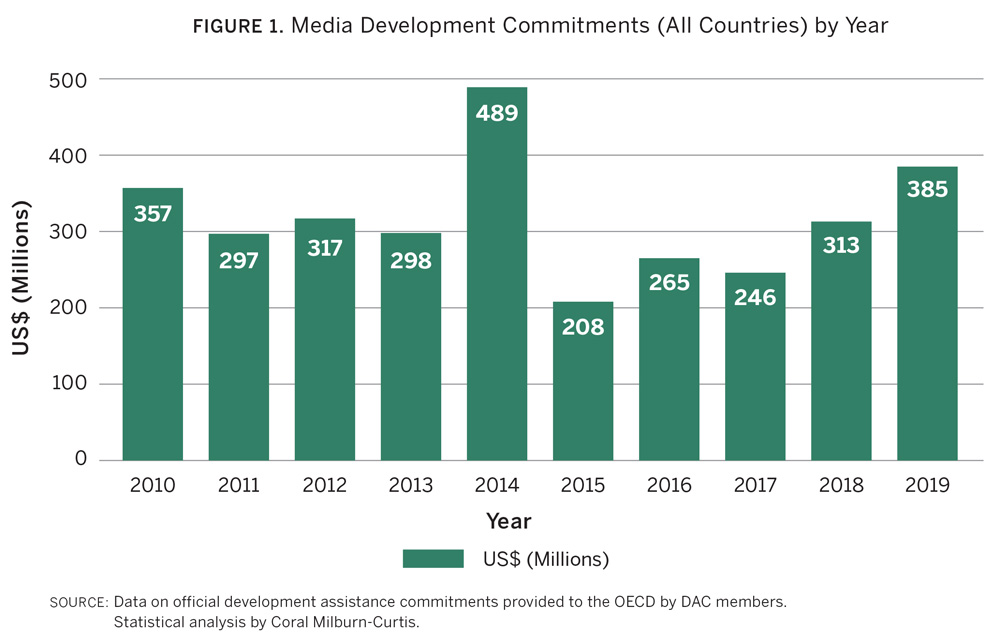

The scale of the problem facing global independent media requires a more robust and sustained commitment by the world’s established democracies. However, in the decade from 2010 to 2019, funding to the media sector as part of official development assistance (ODA) stagnated at roughly 0.3 percent, or, on average, between $300 million and $400 million annually of the roughly $200 billion allocated to foreign aid from official donors.3 To put this into perspective, between 2014 and 2018, Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) spent, on average, over $20 billion per year on health, $18 billion per year on humanitarian assistance, and over $10 billion annually on education.4

The scale of the problem facing global independent media requires a more robust and sustained commitment by the world’s established democracies. However, in the decade from 2010 to 2019, funding to the media sector as part of official development assistance (ODA) stagnated at roughly 0.3 percent, or, on average, between $300 million and $400 million annually of the roughly $200 billion allocated to foreign aid from official donors.3 To put this into perspective, between 2014 and 2018, Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) spent, on average, over $20 billion per year on health, $18 billion per year on humanitarian assistance, and over $10 billion annually on education.4

A more holistic vision for media development is required—one that works, when possible, with reform-minded recipient country governments to build and implement a transformational agenda for the independent media sector. Such an approach requires investing in legal and regulatory structures, building local media capacity at national and regional levels, reforming the business environment for independent media, and catalyzing private capital to grow and scale the most promising news organizations. Journalist associations and civil society organizations committed to upholding a democratic public sphere must also have the capacity to shape the enabling environment for news media. But the amount of aid allocated to fostering a free and open press does not begin to address the enormity of challenges the sector faces and is woefully insufficient to advance the transformational agenda needed to save independent journalism.

There is reason to be cautiously optimistic that this trend is changing. The major bilateral aid agencies have, rhetorically at least, redoubled their support for media in the past few years. ODA to media development totaled $385 million in 2019, the highest since 2014. The international community has increasingly recognized independent media as a critical institution for sustainable social and economic development in recent years. This heightened attention is evident in the commitments made during the US Summits for Democracy in 2021 and 2023,5 and in the pledges of the 50 countries that have joined the Media Freedom Coalition.6

However, as this analysis shows, renewed attention to media development, press freedom, and freedom of expression as priority areas of international cooperation has yet to translate into substantial increases in aid to the media sector. And global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, economic recessions, and record-breaking inflation have created new priorities for development assistance. Several major donors have put media support on the backburner in the face of these global challenges.

An analysis of ODA to media provides one lens to assess and monitor the extent to which the needs of independent media organizations in developing and democratizing countries are being met by the international cooperation and assistance architecture. There are limitations to what the data can illustrate. The data can tell how much money is allocated to support independent media, and the countries and regions that receive aid, but it cannot reliably tell how much money is actually spent nor how it is being spent. Nonetheless, assessing aid flows to independent media over time keeps a finger on the pulse of major donors’ aid agendas, showing the extent to which it is prioritized, if this is changing over time, and whether smaller aid agencies are rising up as new media donors to address the shortfall.

Methodology

This study analyzes trends in media development funding between 2010 and 2019 and looks at donor priorities going forward.7 Taking a historical look, it asks: how much funding have the major OECD DAC donors committed to media assistance and what are their main approaches? It also looks forward and asks: what are the prospects for new commitments, investments, and funding approaches aimed at protecting free and independent media by  major bilateral donors? This study has two components. First, an analysis of development finance data collected annually by the OECD DAC between 2010 and 2019 sheds light on the amount and nature of ODA allocated to media development and how that has changed over time. Second, in-depth interviews were conducted with several of the donor agencies that allocate the largest amounts of funding to media assistance and major international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) that implement media support programs. These interviews were supplemented with a review of available reports from these organizations, including research reports, program evaluations, and financial information. While media development support via ODA represents one of the biggest and most important components of funding, it is not the totality of global investment. These figures do not include media development efforts made by private philanthropies and other foundations, nor do they take into account private sector investments in news media.

major bilateral donors? This study has two components. First, an analysis of development finance data collected annually by the OECD DAC between 2010 and 2019 sheds light on the amount and nature of ODA allocated to media development and how that has changed over time. Second, in-depth interviews were conducted with several of the donor agencies that allocate the largest amounts of funding to media assistance and major international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) that implement media support programs. These interviews were supplemented with a review of available reports from these organizations, including research reports, program evaluations, and financial information. While media development support via ODA represents one of the biggest and most important components of funding, it is not the totality of global investment. These figures do not include media development efforts made by private philanthropies and other foundations, nor do they take into account private sector investments in news media.

There is not a hard and fast definition of “media development” and the definitions that do exist are contested and lack clarity.8 For the purposes of this research, media development is defined broadly and includes support to independent news media, support to civil society organizations that work to improve the legal and regulatory environment for independent journalism, and support that aims to foster development, good governance, and democratic accountability outcomes via media. Aid to international broadcasting, information and communications technology infrastructure, public service messaging, and public diplomacy are excluded where the data are sufficiently granular to allow such exclusions to be made.

What the Data Tell Us—ODA to Support Media 2010-2019

Analysis of data reported annually by DAC members on their ODA commitments to media from 2010 to 2019 reveals critical insights about the prioritization of media as part of development assistance.9

Media Development Commitments by Year

ODA to media averaged a total of $317 million per year in constant prices between 2010 and 2019.

Over that 10-year period, despite increased global attention to the importance of independent journalism, media freedom, and freedom of expression as cornerstones of democratic development and economic progress, commitments to media development remained largely stagnant, accounting for 0.3 percent of ODA.

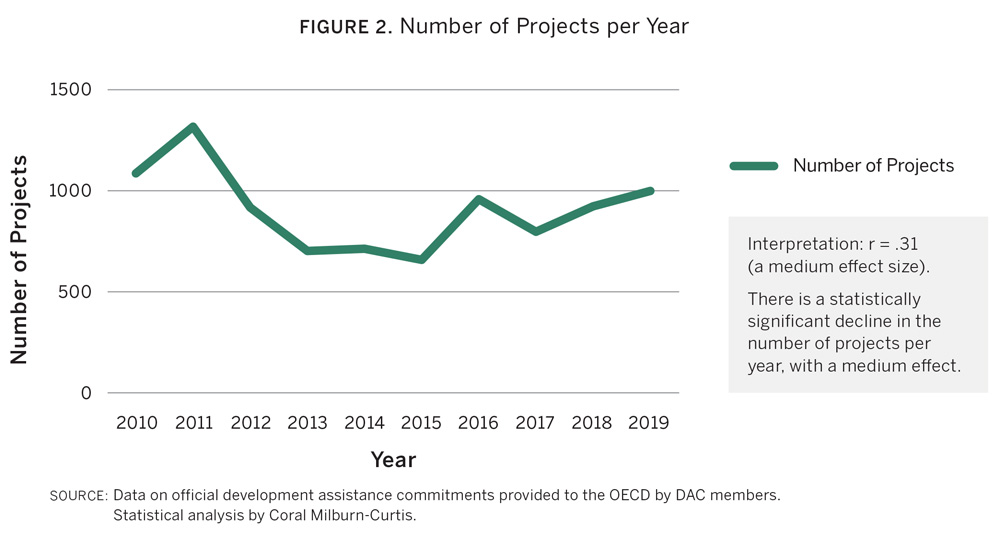

Among the DAC donors, aid to the media sector largely flatlined since 2010. Moreover, the gross number of projects decreased by an average of 21 per year, resulting in an average drop of about $2.3 million per year to the sector.

Global Media Assistance: Providers and Recipients

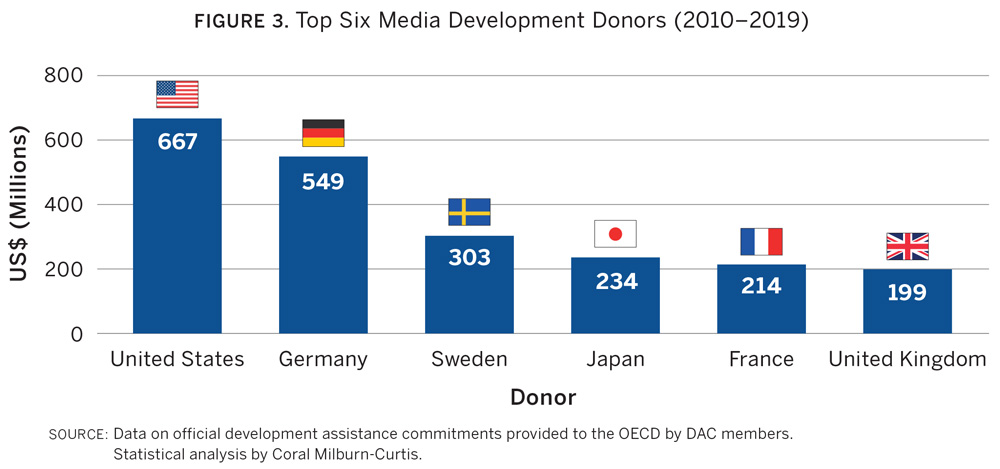

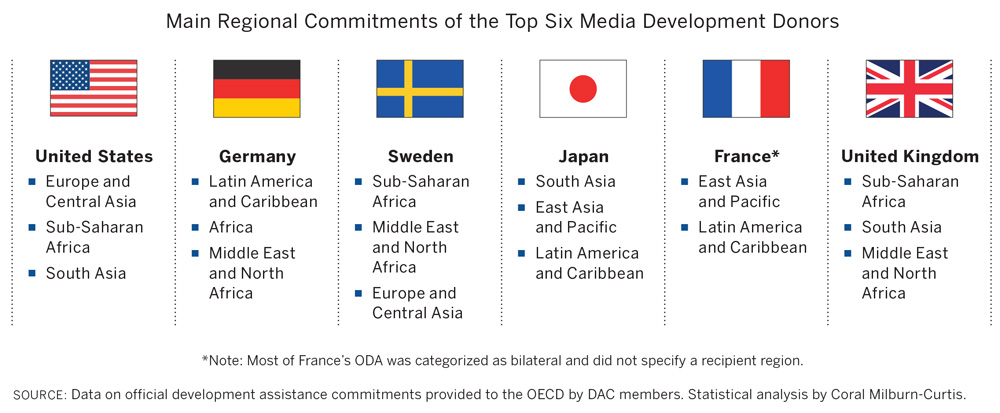

Judging by the average amount of aid allocated to media assistance over the 10 years, the top six donors were the United States, Germany, Sweden, Japan, France, and the United Kingdom.

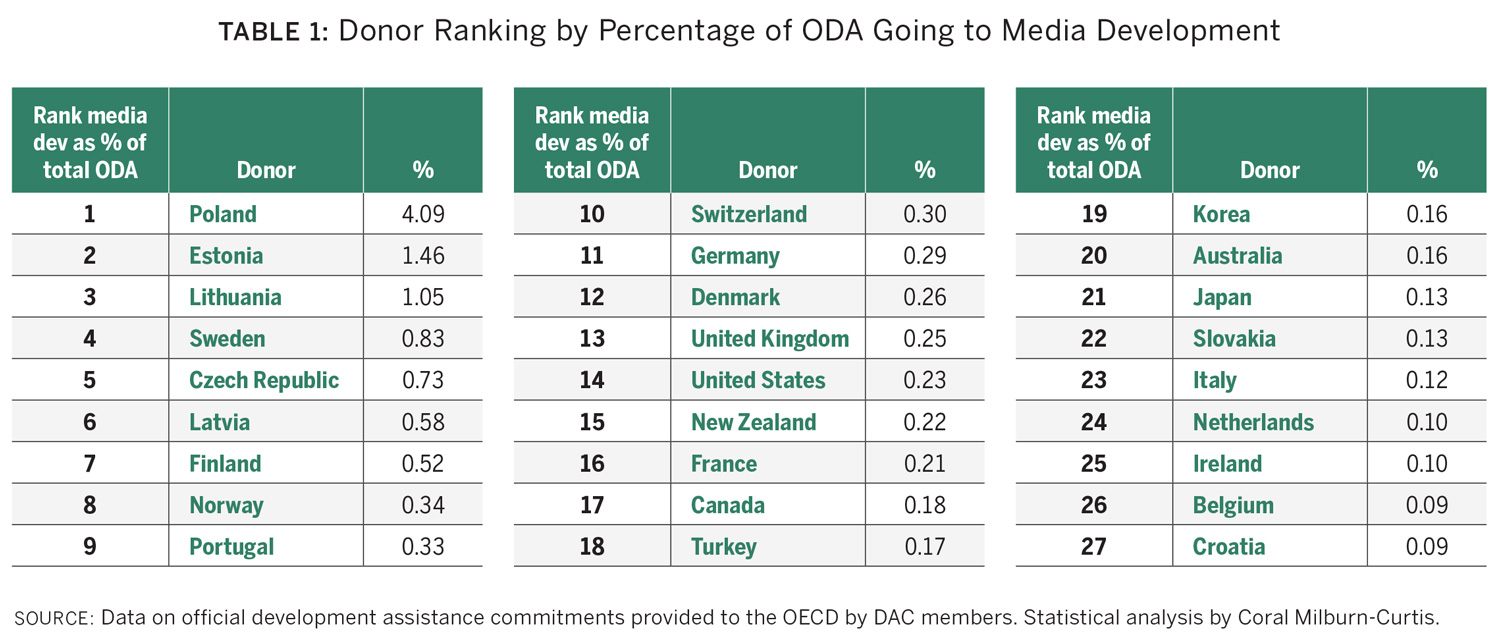

Although these countries made the largest commitments over the 10 years analyzed, they are also among the countries with the largest gross national incomes and, as such, have the largest commitments to ODA overall in terms of dollar amounts. Yet, their media assistance ranks lower when analyzed according to the proportion of overall ODA they commit to the sector, with the United States at 0.23 percent, Germany at 0.29 percent, Sweden at 0.83 percent, France at 0.21 percent, and the United Kingdom at 0.25 percent. Only Sweden ranks in the top five according to proportion of total ODA committed to media and allocates funding at a level significantly higher than the DAC average.

Several small donors, on the other hand, rank higher in terms of the proportion of overall ODA committed to media development. While the amounts remain very modest, it appears that some countries are punching above their weights. Estonia, for instance, commits just 0.16 percent of gross national income to development aid,10 well below the 0.7 percent target set by the DAC, yet allocates 1.5 percent of ODA to media development. Surprisingly, Poland tops all 32 DAC countries, with nearly 4.1 percent of ODA committed to media development, the majority of which is spent supporting media in Belarus and Ukraine.11

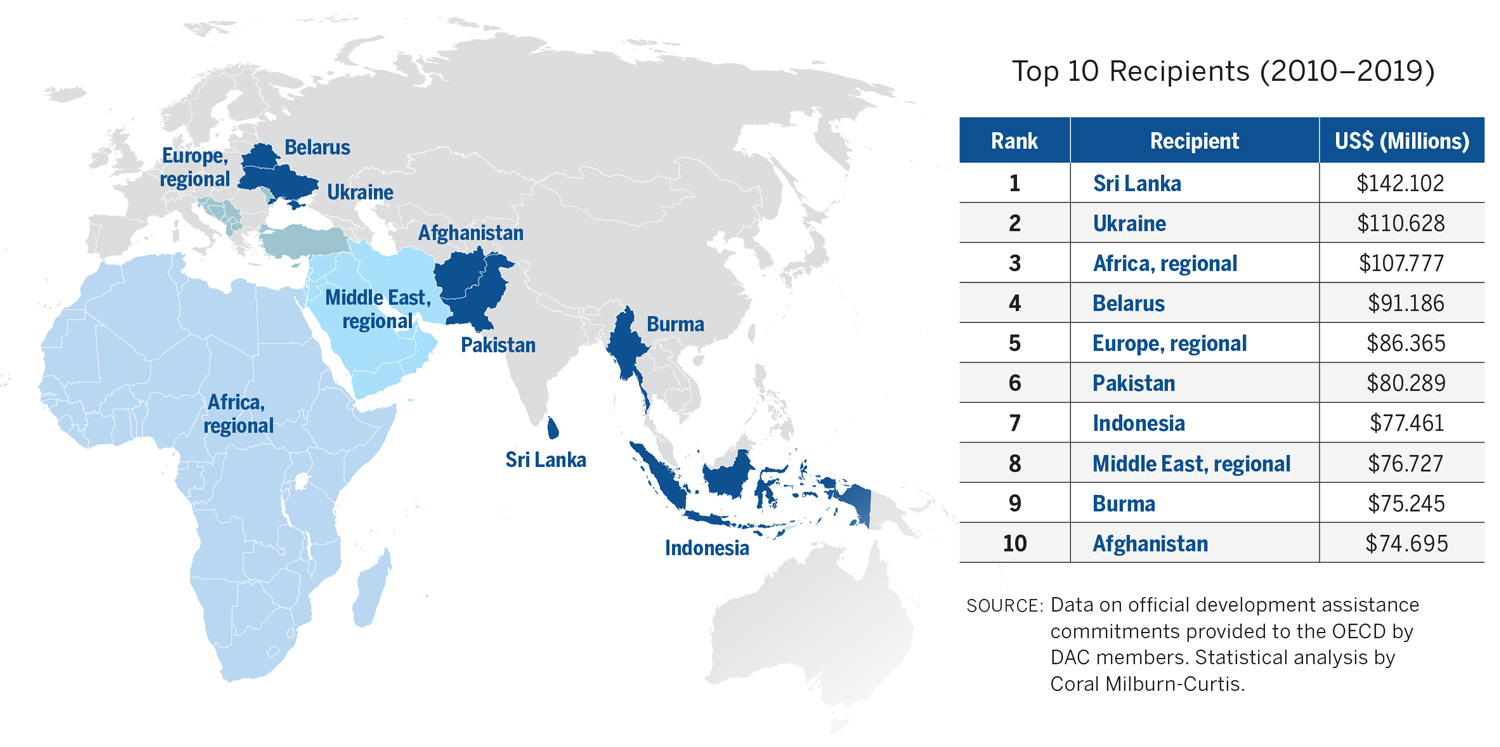

The countries and regions that received the largest shares of media development aid between 2010 and 2019 were Sri Lanka, Ukraine, and “Africa regional;” however, most recipient data were “unspecified.”

A Closer Look at the Top Six Donors

Analyzing data from the top six donors—the United States, Germany, Japan, France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom—allows for a robust perspective on overall media assistance, given that they account for most total official aid to the media sector. Many of these donors are also the most active and influential media supporters in terms of international cooperation and coordination, evidenced by the numerous multilateral initiatives they are spearheading, such as the Media Freedom Coalition, Summit for Democracy, and Forum on Information and Democracy. Some of these aid agencies also have specialized media support strategies and dedicated experts focused on the media sector on staff. However, several NGO representatives have seen a decline in the number of dedicated specialists among donor agencies. One Dutch INGO representative noted, “The level of staff, expertise, and higher-ranking officers involved in media support, media assistance, and safety of journalists is shrinking.”12

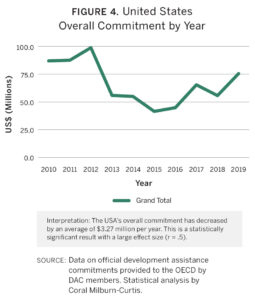

Unites States

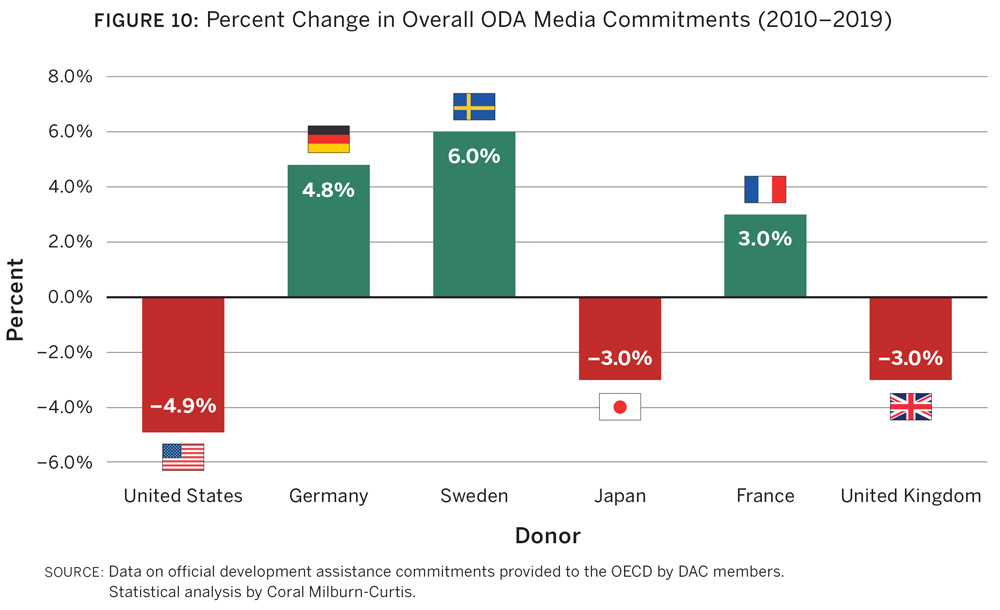

The United States tended to decrease its commitments to media development over the years studied, with a statistically significant mean decrease of over $3 million per year, amounting to an almost 5 percent reduction over the 10-year period.

The United States tended to decrease its commitments to media development over the years studied, with a statistically significant mean decrease of over $3 million per year, amounting to an almost 5 percent reduction over the 10-year period.

With respect to priority regions, these have also shifted over time, with increases to the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Central Asia, and decreases to the Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, East Asia, and the Pacific.

From 2010 to 2019, Europe and Central Asia received the highest level of media assistance from the United States, with approximately $273 million committed in the region over the 10-year period, followed by sub-Saharan Africa at $137 million.

Most US commitments were delivered to NGOs and civil society in recipient countries, with a small uptick over the 10 years in media assistance delivered to the private sector, multilateral institutions, and academic institutions. From 2010 to 2019, the US government decreased its delivery of media assistance to the public sector.

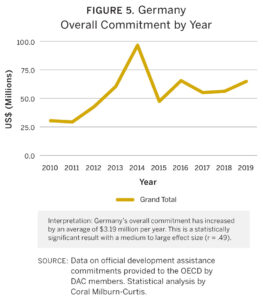

Germany

Germany increased its ODA commitment to media assistance over the 10 years, with an average increase of $3.2 million per year, which is a 4.8 percent rise over 10 years.

Germany increased its ODA commitment to media assistance over the 10 years, with an average increase of $3.2 million per year, which is a 4.8 percent rise over 10 years.

The Latin American and Caribbean region received the highest amount of German media assistance, followed by sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa.

By far, the public sector was the top recipient of German ODA to media, representing $429 million over the 10-year period, with NGOs and civil society working in the media sector receiving just $91 million. Between 2010 and 2019, Germany increased its commitments to the public sector, the nonprofit sector, academic institutions, and the private sector, and decreased allocations to multilateral institutions.

Sweden

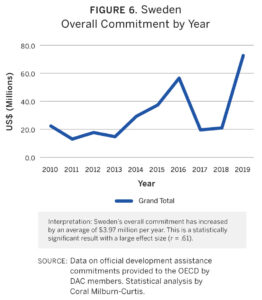

Sweden increased its commitments to media assistance between 2010 and 2019 by roughly $4 million per year, representing a 6 percent increase overall.

Sweden increased its commitments to media assistance between 2010 and 2019 by roughly $4 million per year, representing a 6 percent increase overall.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s media sectors were a priority for Sweden, receiving the highest amount of aid at around $85 million over the 10-year period. Sweden increased its overall commitment to media support in all regions other than Latin America and the Caribbean, which saw a decrease over the 10 years.

Sweden prioritized NGOs and civil society as recipients of media aid, with $207 million allocated to this channel of delivery, followed by multilateral institutions, representing approximately $41 million over the 10-year period. Sweden decreased its media assistance to public institutions between 2010 and 2019.

Japan

The Japanese government decreased its ODA to the media between 2010 and 2019 by an average of almost $2.1 million per year, amounting to a 3 percent decrease over 10 years.

The Japanese government decreased its ODA to the media between 2010 and 2019 by an average of almost $2.1 million per year, amounting to a 3 percent decrease over 10 years.

The lion’s share of Japan’s commitments was directed to countries in South Asia, with the region receiving $157 million to media support over the 10 years. The only region that experienced an increase in Japanese media assistance was Europe and Central Asia, with all other regions facing declines in Japan’s aid to the sector.

Virtually all of Japan’s aid to media was delivered to the public sector, with very little support channeled to civil society, NGOs, academic institutions, or multilateral organizations.

France

France increased its media support over the 10-year period by an average of around $2 million per year, representing a 3 percent increase.

France increased its media support over the 10-year period by an average of around $2 million per year, representing a 3 percent increase.

Because a number of entries do not specify the beneficiary region or country ($128 million), it is difficult to determine which regions received the highest proportion of French media assistance. East Asia and the Pacific regions appear to have been a priority, receiving almost $66 million of media aid from France between 2010 and 2019, yet that amount decreased over time.

Most of the French assistance to the media was channeled to the public sector in recipient countries, with little aid committed to NGOs and civil society, and virtually no aid directed to the private sector, academic institutions, or multilaterals.

United Kingdom

Like Japan, the United Kingdom decreased its commitments to media development from 2010 to 2019, with an average drop of around $2 million per year, amounting to a 3 percent reduction overall.

Like Japan, the United Kingdom decreased its commitments to media development from 2010 to 2019, with an average drop of around $2 million per year, amounting to a 3 percent reduction overall.

Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia were priority regions for UK aid to the media sector, yet support to these countries decreased over the 10 years in line with broader cuts to the sector overall.

The United Kingdom reduced media assistance delivered to NGOs and civil society between 2010 and 2019. Aid to the private sector, public sector, academic institutions, and multilateral institutions saw a small uptick, with the greatest increase in aid channeled to the private sector over the 10 years.

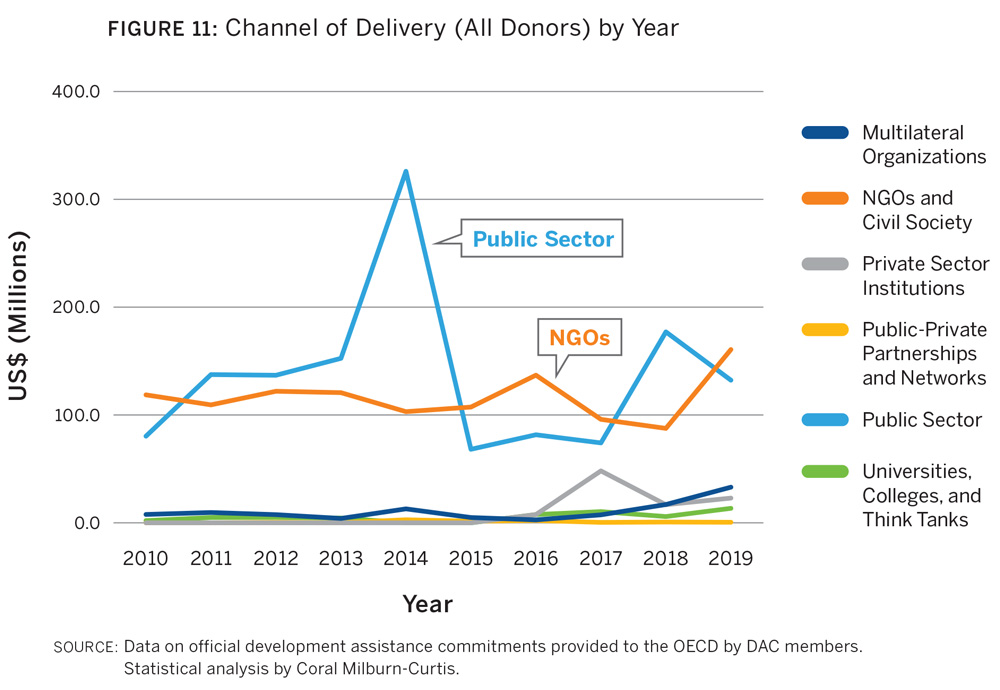

Channel of Delivery

How donors deliver aid—the “channel of delivery”—can shed light on how and with which coordinating actors a donor plans to address a specific challenge. Per the OECD’s definition, the channel of delivery refers to the “first implementing partner” that receives the funds, which is the entity that is ultimately accountable for executing a project.13 Potential channels of delivery include governments, multilateral institutions, NGOs (international and local), private sector organizations, and universities and think tanks. The channel of delivery is an important element in understanding support because it speaks to how donors are trying to spur development. For example, in some cases providing direct support to recipient governments may be considered the best way to effect change as it can increase local buy-in and ownership.14 Bolstering civil society capacity through NGOs may be considered a more effective mechanism in places where government support for human rights and media freedom is in question.

Between 2010 and 2019, 44 percent of media development ODA was allocated to public sector institutions, while 36 percent was allocated to civil society organizations, either INGOs or NGOs, based in recipient countries and regions. The remaining 20 percent was allocated to other channels, including multilateral institutions, the private sector, and universities and think tanks. During this time, there was a statistically significant increase in media development funding being channeled through the private sector (+5.3 percent), multilateral institutions (+2.4 percent), NGOs (+1.4 percent), and universities and think tanks (+1.3 percent).

The channel of delivery for media development projects differs somewhat from overall ODA. For example, recent analysis of overall ODA flows in the year 2020 indicates that 51 percent of ODA was channeled through the public sector, while just 13 percent was channeled through NGOs.15 This suggests that aid to media is more likely to be channeled to NGOs and civil society than aid to other sectors, though the public sector overall remains the largest recipient.

In other respects, ODA to media followed shifts in overall ODA. For example, there was an uptick starting in 2016 in aid channeled to the private sector.16 Donors also increased their use of multilateral organizations as channels for delivering aid, a trend that is also seen in aid to the media sector.17

What the Donors Say

Interviews with major bilateral donors engaged in democracy assistance and aid to the media sector confirm that there is a renewed interest and urgency in supporting independent media as part of their development and governance agendas. Rising authoritarianism, rampant disinformation, toxic social media, the “democratic crisis,” rising threats to journalist safety, the effects of COVID-19, and the war in Ukraine were mentioned repeatedly as reasons for increased attention to media development from 2020 to 2022.

“I think there’s certainly more openness and interest in discussing media and the role of media,” an OECD representative said. “Russian interference campaigns in some donor countries like the United States and the United Kingdom are now well documented. These have really woken up . . . the minds of several people and who are now saying what can we do about this?”18

However, increased attention to the media does not necessarily translate to greater investment. Aid to media development is still relatively low in the face of other global financial pressures and development priorities. Nevertheless, overall funding to the sector at least seems to be holding steady and not decreasing overall. INGO representatives are more cynical about donor governments’ real commitments to media than representatives from the agencies. In the eyes of most interviewees from implementing organizations, the OECD DAC donors are not stepping up to the plate on media support and are not responding to the challenges independent media are facing with adequate action or with sufficient, stable, and predictable funding. “Independent media was a key . . . priority for [British] foreign policy, but it doesn’t seem to appear in the speeches or policy documents as a priority since 2019. Under successive foreign secretaries it has begun to crumble,” said a representative of BBC Media Action. “There’s been a radical reduction of funding, a deceleration . . . You cannot have an effective strategy for supporting independent media in the world unless you’ve spent more money. We’re living through a media extinction!”19

The findings from these interviews give additional context to the policy and financial commitments to media development over the last decade and how these policies have, in some cases, changed over time in reaction to perceived successes and failures in media support. They also provide a window to understanding the present, which is impossible to determine using the OECD DAC dataset because of the lag times between commitment, reporting, and publishing the data. Interviews give insight into how the major media donors are currently organizing and articulating their media support, particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis in Ukraine. Finally, the interviews shed some light on the possible future of media support among the major donors, including whether they are likely to increase their commitments to and investments in media over the next few years and the corresponding rationales.

The Shifting Field of Media Development

Driven by global events occurring between 2015 and 2019 and the evolving shift in the media landscape brought about by digitalization, social media, and the rise of disinformation, many donor agencies have taken greater interest in media development and adjusted their priorities. These five years were marked by various global shocks to media and information freedom, including the elections of Donald Trump in the United States, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, and Viktor Orbán in Hungary, amid a general rise—and emboldening—of autocratic leaders around the world. Worldwide, 2018 was the worst year on record for deaths among journalists. Disinformation and the weaponization of “fake news” have generated an awakening to the toxic side of the internet. Finally, there is growing recognition of the dire financial state of news media globally.

These events and worrying trends appear to have galvanized donor agencies to strengthen their policy statements in favor of media development, as well as their financial support. In addition to policy statements and modest financial investments, these trends also led to the establishment of international coalitions toward the end of the decade, such as the Media Freedom Coalition and media cohorts established as part of the US Summit for Democracy.

“Media has received more attention in the last five years. Ten years ago, we assumed we had shared values when we came into a country, but that’s no longer the case . . . and media is a factor in this mismatch and is a factor in rising authoritarianism,” said a representative of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.20 A representative of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs echoed this sentiment: “The overall rationale hasn’t changed much, which is that a free press is a condition for a functioning democracy . . . The thing that has gained more attention over the past few years is the safety of journalists because we see the rise of threats and violence increasing . . . That is something that’s gained more attention and therefore funding. Khashoggi’s murder was a turning point.”21 And the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) has “been fairly consistent in supporting media as a sector [but] there has been increasing recognition that there is an attack on journalists and on their safety,” said an agency representative.22

France is another donor to have renewed its commitment to media. According to interviewees at the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, the Arab Spring in 2011 was a turning point. Representatives interviewed were emphatic about what one of them called a prise de conscience (realization) about the importance of media from a policy perspective, both in France and globally. “This prise de conscience that we’ve had has been the most remarkable thing,” said a ministry representative. “The trigger was the rise of civil society in [the] Arab Spring in 2011 and then in 2018-19 our Forum on Information and Democracy—a big involvement by governments in response to disinformation. We must absolutely devote funds [and] energy and we must mobilize for this media freedom agenda. It is a global discourse.”23

Since then, French government policies have developed in reaction to a rise in disinformation worldwide. “There has been a heightened interest in media support because of all the disinformation issues—this is both important in France and across the EU,” according to a representative of the French Development Agency (Agence Française de Développement; AFD).24

The search for sustainability and long-term viability for independent media is a perennial issue in media assistance. A representative of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) regarded sustainability as a question of entrepreneurship and good business models. “The majority of efforts to make media more entrepreneurial have succeeded,” he said, especially in middle income countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Serbia, “where we choose serious outlets that are entrepreneurial.” He continued: “About six years ago, in some contexts there was a pivot in USAID to go away from grants to [a] greater emphasis on business models and self-sustaining newsrooms—[in] Serbia, in particular.”25

A French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs representative also emphasized the importance of supporting private, entrepreneurial media: “There is also now more a focus on privately owned/commercial/independent media. This is a success for us to have started these kinds of projects.”26

The government of Japan has an approach to the sustainability challenge that is unique among OECD DAC donors. Japan does not prioritize the development of a private media sector in its media assistance strategy. Rather, it supports national public broadcasters in all recipient countries (i.e., Nepal, Ukraine, South Sudan, Kosovo, Burma).27 A representative of the Japan International Cooperation Agency regarded the agency’s media support in Kosovo as a success for public service broadcasting and for national unity: “Originally there were two channels, for Albanians and Serbs—we tried to unite them for reconciliation. So, they started to collaborate. We united the master control room. They improved their capacity for production. So that was a successful case.”28

The necessity of supporting media literacy as a strategy against mis- and disinformation was also mentioned by several donor representatives. For example, an interviewee from Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) identified media literacy work in Namibia and across southern Africa as a notable success during the last decade “because Deutsche Welle Akademie [DWA] started a huge media and information literacy program, which became part of the Namibian school curriculum. DWA in general has become a leader in media literacy, especially important in countries that are [already] suspicious of media. It has a positive effect.”29

A US State Department representative emphasized training on journalist safety as a priority, highlighting the department’s support for a series of physical hubs around the world, which are “space(s) to bring journalists in to train them on how to operate more safely, and how to improve their security situation. It is successful because it includes not just physical but also digital security training. It has psychosocial care built into it.”30 Several other donors and INGOs mentioned enhanced attention to journalists’ safety across the world.

Another marked—and almost universal—change over the last decade was a pivot toward digital media and tackling all the negative aspects of technology and the internet. For example, a representative from the Netherlands Foreign Ministry said, “Digital/cyber and online media has also grown a lot—human rights in this space [is] getting more attention.”31

The French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs expressed pride for encouraging its implementing partners, notably the French media development agency Canal France International (CFI), to make a “paradigm shift towards digital” in the last few years. “For example, we realized in Tunisia it was necessary to pivot towards young people. [We now focus on] social media and influencers, no more on national television . . . a big emphasis on fact checking, verification, inculcating ethics.”32

Regarding social media, a representative of the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs pointed to two projects, “one called Media Sahel—financed by AFD since 2019. It is going very well—fighting radicalization. We are proud of it. The other is a project run by the Institut Français, but financed by the EU, called Safir, which also fights radicalization with a presence on social media.”33 The French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs has funded various aspects of digital media including support for bloggers.

Tackling mis- and disinformation has emerged as a major theme. As the representative from the Global Forum for Media Development (GFMD) noted, “more and more donors are concerned about disinformation.”34 Mis- and disinformation is also being prioritized in the wake of broader attacks against democracy and deepening authoritarianism: “I think disinformation has punctuated the point that we really need to be addressing these issues much more forcefully,” a US State Department representative said. “It’s a part of the reason that the president made it part of the Summit for Democracy.”35

A representative from the French government’s AFD saw disinformation as harmful to French interests: “I see a new interest in media in the wake of disinformation used against France in Mali . . . everybody wants to fund the fight against disinformation and misinformation . . . there’s a general heightened consciousness of the power of disinformation and the negative aspects of social media.”36

In Denmark, a representative of International Media Support (IMS) pointed to the launch of Tech for Democracy37 by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the fact that Denmark had recently appointed a “tech ambassador.” From IMS’s point of view, this is proof that “information is far higher on the political agenda” and that “we [IMS] have pushed public interest journalism into tech. That has been a game changer with the [Danish] Ministry of Foreign Affairs.”38 The representative from USAID similarly emphasized a growing recognition within the agency about the need to “focus on technology . . . We are [now] having dedicated people focus on internet freedom, and the intersections between the internet and democratic societies as well as on disinformation . . . each one of these things we are recognizing as critical problems, not just for democracy, but for quality of life.”39

COVID-19 increased awareness of the dangers of mis- and disinformation. From 2020 onwards, mis- and disinformation about COVID-19 spread rapidly, leading to what the World Health Organization described as an “infodemic.”40 The representative from BMZ was one of several donors that highlighted the pandemic as a reason for increased media assistance: “In 2021 we had 40 million [euros], we got 10 million [euros] more because of COVID-19. We made a special program for media resilience in crisis.”41

The crisis in Ukraine and the mis- and disinformation it has generated is another rationale for media assistance for many of the donors interviewed: “From the media development point of view, the [Ukraine crisis] increased awareness in the ministry of the problem of the information war . . . obviously in Ukraine, but also in Africa, where they see a rise of disinformation, mostly Russian disinformation,” said an interviewee from France’s CFI.42

A major change in media development over the last decade is a trend toward a more bottom-up, demand-driven approach. “The transfer of knowledge [was] a ’90s thing, but that’s changed now,” said a representative from GFMD. “In most cases it’s not necessary anymore for all of us to go and explain in [developing countries and emerging democracies] how the models from the western or northern part of the world work . . . People in those regions know much better.”43

A spokesperson for CFI said, “France has evolved in its support to media; it has a less paternalistic approach to media than say 15 years ago. Now it is bottom-up approaches to media sustainability.”44

Delivering the right kinds of capacity building and in the right way is also an area where a lot of learning is happening. Basic and specialized journalism training is still a key plank of most donors’ media support programs. But Sida in Sweden is among some that are questioning journalism training: “Ten years ago [our] focus was more on the basic training and skills for journalists and less on financial support to news production . . . [this is] one aid modality that has been a success . . . We are one of the few donors that advocate core support . . . being allowed to make your own decisions makes the partners much more relevant. And it also increases our legitimacy vis-à-vis local partners.”45

Persistent Weaknesses in the Field

Nevertheless, the trend toward renewed policy interest in media between 2015 and 2019 did not always result in successful media development interventions nor was it always matched by financial commitments. Although there was an uptick in spending between 2016 and 2019 (e.g., France and Sweden both demonstrated an increase in funding, which corroborates the statements from the government representatives above), it was not significant overall, and not all donors increased their spending. In fact, the average annual media development commitment by OECD DAC donors in the last five years of the last decade ($283.4 million in 2015-2019), was lower than the annual average during the first five years of that decade ($351.6 million in 2010-2014). (See Figure 1.)

Some of this can be explained by the vagaries of politics and the squeeze on domestic budgets. For example, in the Netherlands, there were severe right wing–inspired cuts across government budgets starting in 2015, including for media support, according to some INGO representatives. And in the United Kingdom, previous strong financial commitments to media development by the Department for International Development (DFID) between 2012 and 2017 were negatively affected by reductions in the aid budget, in line with Conservative Party policy, especially after Boris Johnson was elected in 2019. Furthermore, as some observers reported, media expertise was lost when DFID merged with the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office in 2020.

In terms of the effectiveness of media assistance programs on the ground, a handful of countries came up as examples of unsuccessful efforts. Several respondents mentioned Burma (Myanmar) as a country where a lot of investment in media took place before the coup in February 2021, which is now regarded as having been wasted. For example, the interviewee from BMZ said, “Myanmar was a failure—we had a successful program collaborating with community radios, but it all had to stop. We invested more than 10 million [euros] and now it’s a failure; we do not know what will happen in the years to come because of the coup . . . We still have a program working with exiled journalists who are based in Bangkok, but that’s about it.”46

Others also mentioned wasted investment in Afghanistan, mainly because of the Taliban takeover in 2021, which undid two decades of high international aid flows to independent media. But there were also failures due to a lack of strategy among donors. For example, the interviewee from BBC Media Action said “. . . [There was] very effective early support to the media in Afghanistan. And then by 2012, on the back of a kind of huge splurge in spending . . . was certainly a very steep hill of reductions in spending. With very little clear strategic clarity or coherence . . .”47

Media development has also been a victim of regime changes in West Africa. For instance, according to interviewees from the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, “We had a disappointment over all the energy and money we spent supporting those famous national public broadcasting agencies—the results cannot really be seen on the ground. For example, we tried to train ORTM48 in Mali—to professionalize it—but our efforts were reduced to nothing when the new regime came in.49 France is not alone in having these problems, which are beyond our control. So [now] we do not want to invest in these archaic media systems that don’t adapt.”50

Another aspect of media support deplored by several interlocutors was training outside journalists’ place of work and capacity building for media workers that is not grounded in their local reality. For example, one INGO representative criticized the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and other donors for continuing with this model: “For me, what is a failure is this training of journalists, like bringing journalists in a hotel room for 10 days . . . we keep on telling them that this is just dust on the ground. I mean, it does not make any difference.”51

The funding of only short-term projects was another common criticism. For example, a representative from BBC Media Action said, “I’m very worried that an awful lot of money has been spent on very short-term, small-scale interventions of a year or less in nature.”52

The funding of only short-term projects was another common criticism. For example, a representative from BBC Media Action said, “I’m very worried that an awful lot of money has been spent on very short-term, small-scale interventions of a year or less in nature.”52

While commercial sustainability efforts may have been a success for USAID, most of the interviewees said that achieving sustainability for media outlets was still seen as a struggle. For example, a representative from BBC Media Action said, “Donors are struggling to come to terms with the fact that the sector is no longer commercially self-sufficient.”53 Similarly, a representative from DWA said, “The challenges have been the usual ones in our sector . . . not enough emphasis on long-term sustainability.”54 And, although the Japan International Cooperation Agency is proud of Japan’s record, such as in Kosovo, where long-term national government support has been secured for the national public broadcaster, he conceded that achieving real public ownership is very difficult. In South Sudan, for example, “it’s not easy to change the mentality of not only the journalists, but also the officials of the ministry . . . the politicians say that they want to keep the broadcaster as the mouthpiece of the government.”55

A representative from USAID acknowledged that commercial sustainability cannot be expected in many places. “Some countries were too difficult for an independent outlet to achieve financial independence . . . Somalia, for example, does not have a [media] market—all you can do is grow the audience, provide training, etc., [and] where markets are really weak, it is back to older forms of support—training, grants, core support, safety, and survival.”56

This question of core support for media organizations and outlets feeds into an ongoing debate about localization of media development, which several interviewees mentioned as a concern. An interviewee from GFMD was particularly vocal on this subject: “There is not enough localization and ensuring funds stay in-country . . . a concerted effort [is needed] to build local capacity in management and grant management.” Her advice was for donors and media development INGOs to “help with fundraising, security, digital, lobbying, advocacy, and developing specific expertise” and added that “this expertise is also needed in the donor agencies themselves.”57

Several donors mentioned the risks of entrusting funds to local media outlets and media support NGOs. For example, a representative from France’s AFD was pessimistic about localization: “It’s really tricky to fund local actors because of accountability; they often don’t have the proper resources.”58 An interviewee from IMS in Denmark said, “accountability is a problem and, for example, we have not received funding for Afghanistan because they [the Danish Foreign Ministry] have not trusted us to manage properly with local partners due to the difficult political position and the Taliban coming in.”59

So, overall, localization is unlikely to happen any time soon. For instance, an interviewee from CFI foresaw a time when, “ideally CFI should disappear as this would be a true mark of its success.” However, he predicted this would not happen for 20 years.60

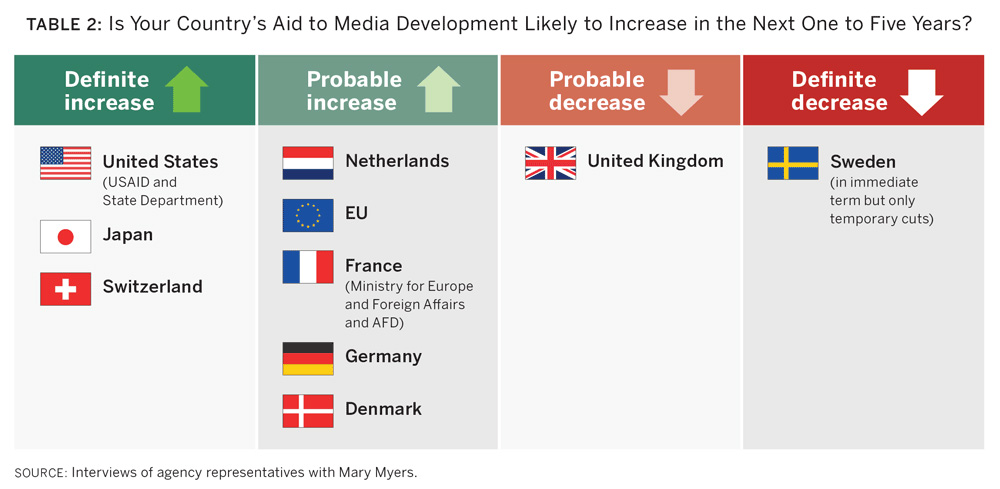

Prospects for Media Support Beyond 2023

Interviewees were asked to give their impressions on whether funding to media development would increase or decrease over the next one to five years. The answers given are not official representations of future ODA priorities and are only indicative. Nonetheless, the responses provide a glimpse into whether staff at the major donor agencies perceive that media assistance will receive greater or less attention within their institutions over the next several years.

In the United States, interviewees from the State Department and USAID pointed to recent commitments by the Biden administration to media support, including $20 million granted to the International Fund for Public Interest Media,61 funding to Internews to start a new “media viability accelerator” of between $4 million and $9.99 million,62 and an allocation of between $4 million and $12 million to seed an insurance fund for investigative journalists called the Empowering the Truth Tellers program.63 Congress has also earmarked $20 million to support freedom of expression in fiscal year (FY)2022, up from $15 million earmarked in FY2021 and $10 million in FY2020.64 According to representatives from both the State Department and USAID, there are signals that media assistance will continue its upward trajectory. “There’s not only the greater interest in media but also efforts to actually staff up an expanded portfolio and increase dedicated funding,” according to a USAID representative.65

Interviewees from the governments of Japan and Switzerland reported definite increases in their aid budgets for media assistance but no official announcements have been made.

While the donors from the United States, Japan, and Switzerland indicated that they expect an increase, some donor agencies also expect probable increases in media assistance over the next few years.

Representatives from the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and media support INGOs expect small increases. A representative of the foreign ministry said she believes that funding focused on the digital space will increase, especially relating to mis- and disinformation,66 while an interviewee for Free Press Unlimited predicted that “we may see an increase in human rights funding for media assistance in the coming years . . . I expect we can manage to make media assistance grow . . . because of the media crisis in Ukraine, Russia, Belarus.”67

Officials and INGO representatives from the EU also point to a probable uptick in media funding in the near future. “[Media assistance] is very likely to increase [because of] the increased policy commitments, the notable trends in recent years, and the increasing interest [in issues of information integrity] on the part of EU Delegations,” a representative of Media4Democracy said.68

In France, according to representatives from the Foreign Ministry, AFD, and CFI, media support is likely on an upward trajectory. There is a planned increase in overall ODA from 0.55 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) to 0.7 percent of GDP in 2025. Whether this will impact funding to media development is yet to be seen, but interviewees expect an increase. An AFD representative said, “My feeling is that [media assistance] will remain stable in 2022, but my prediction is that it will increase [in future years],”69 a view echoed by a spokesperson for CFI: “The [funding] trend is an increase–especially on disinformation.”70

In Germany, both the BMZ and its main media INGO partner, DWA, were upbeat about prospects for media assistance in the immediate future because of a commitment of nearly $5.5 million (€5 million) of media aid to Ukraine. However, the longer-term picture for the next five or 10 years is less optimistic, and interviewees expect ODA to go back to 2020-21 levels due to domestic pressures, such as inflation and a fuel crisis. Despite the anticipated decrease from 2022-2023 levels, the representative from BMZ expects that funding for her department, which oversees media, “will stay in place,” noting that “DWA is getting stronger and stronger.”71

In Denmark, a representative from IMS noted increased funding to IMS by the Denmark Ministry of Foreign Affairs between 2020 (€6 million, or nearly $6.5 million) and 2021 (€8 million, or about $8.7 million) and was cautiously optimistic about media support from the Danish government in the future. “We have managed to increase allocations with the ministry. We have been given space to operate on our terms,” he said. “At the moment, there is a fantastic group at the ministry. But it can change, you never know. We are losing some good people in the ministry.”72

While these indications of increases are promising signs for media development in the coming years, two major media development donors expect their support for media to decrease.

The United Kingdom’s financial commitment to media support is on a predicted downward trajectory. UK ODA is down overall73 and the agency is likely to further reduce media support. “The international development strategy doesn’t give much room to do media development and it is just not a high priority of the foreign secretary,” said an interviewee with the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office.74

The United Kingdom’s financial commitment to media support is on a predicted downward trajectory. UK ODA is down overall73 and the agency is likely to further reduce media support. “The international development strategy doesn’t give much room to do media development and it is just not a high priority of the foreign secretary,” said an interviewee with the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office.74

Despite this bleak assessment, a representative from BBC Media Action had a more optimistic outlook, noting that the current situation will change as political tides shift. “I think the British government should and will commit more to media in the near future,” he said. “Can you combat [development] issues without free media? No. You cannot combat climate change without a solid information space and free flow of information. Media is fundamental to navigating the 21st century . . . If we want to achieve these goals, we need to invest in media . . . Assuming logic prevails, and an assessment is made, I think it may well substantially increase again.”75

In Sweden, Sida has also recently experienced a cut in funding available for media support, but predictions are that cuts are only temporary. A representative of the agency noted, “We have had cuts because of assistance to Ukraine . . . The major brunt of the cuts was on our global strategies. However, this is likely to be only a temporary reduction [for 2022 and 2023].”76

Conclusions

CIMA’s previous analyses of aid flows to the media sector from 2010 to 2015 indicated that the major bilateral donors recognized that support to media is integral to sustaining democracy and good governance. Today, the “democracy and human rights agenda” continues to define donor support to media.

Recent world events (e.g., COVID-19 and the invasion of Ukraine), worrying anti-democratic trends, and the negative side of digitalization appear to have spurred the donor agencies to strengthen their policy statements in favor of media development. But, although the discourse may have intensified, the financial commitments to media have certainly not followed suit. There are some forecasted budget increases, but they are small, and not all donors are making them. On the other hand, only a minority of donors have announced definite cuts, so taken as a whole, Western donors’ financial commitments to media are likely to result in the same levels after 2019, with no dramatic increases in the foreseeable future.

Donor agencies are saying that they are committed to media development and are trying to learn from the past but many of the same challenges that have beset the sector for years remain. And media support is still low on the list of aid priorities and can easily be cut when crises such as COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine strike. In the eyes of the media INGOs, the OECD DAC donors are still not providing adequate, stable, or predictable funding or clear media development strategies. All media INGOs, and many donor officials, are working in a constant state of uncertainty about whether there will be true commitments—or cuts—just around the corner.

There still appear to be more questions than answers in the sector. Among those interviewed for this study, for every donor or implementer who looked back with pride at the last decade’s successes in a country or on a theme, another questioned that same theme or strategy. Each donor agency has its own subtly different priorities and approaches. The more technical aspects—the search for commercial sustainability and the avoidance of aid dependency, how to promote public trust in media, how best to build journalistic capacity, and how to promote localization and a truly bottom-up approach—are some of the issues that still have no solutions.

Nonetheless, compared with a decade ago, there appears to be a better understanding of media among the major donors. They are also increasingly concerned about the impact of technology and digital governance on news media and recognize the dangers associated with social media and information pollution. There is also a greater commitment to multilateral diplomatic efforts, such as the Media Freedom Coalition (started by the United Kingdom and Canada in 2019), the Summit for Democracy (launched in 2021 by the United States), the International Partnership for Information and Democracy (launched by France in 2019), and possibly what may be emerging as a “diplomatic turn” in media development. Donor governments are increasingly talking to recipient country governments and lobbying for changes such as improved journalist safety, an end to impunity for attacks on journalists, trial observations by the international community, granting of emergency visas, and so on.

Finally, the financial picture for media support could be worse, considering the enormous political, security, and economic headwinds that are currently buffeting most of the OECD DAC donor governments. Although media support is still barely attaining 0.3 percent of ODA, at least the major donors are not significantly cutting their aid to journalism. Overall, finance to media development as part of official development aid seems to be holding steady.

Annex

Quantitative Analysis

The quantitative data for this report’s analysis come from the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System (CRS) aid activity database. These include data supplied by the 32 DAC members, including the European Union (EU) bodies that are obligated to report, as well as all the main multilateral organizations, which voluntarily report.77 Donors take at least a year, and sometimes longer, to report their commitments, and thus there is a lag between when a commitment is made by the donor and when it is made available via the CRS database. Data was extracted from commitments listed under the “government and civil society” sector (15153 Media and free flow of information) and under the “communications” sector (22010 Communications policy and administrative management; 22020 Telecommunications; 22030 Radio/television/print media; 22040 Information and communication technology). Trained coders analyzed each project based on its title and description. Projects that did not meet CIMA criteria for media development were excluded. All remaining projects were coded based on the description in the database. For reliability, at least two individuals independently coded the entire database, and any disagreements on codes were later arbitrated.

While these data are quite illuminating in many ways, they have several limitations. First, the data compiled represent spending commitments, not necessarily an accounting of how the funds were ultimately spent. Many things can change between the time governments allocate money and when and how the money is actually spent. Therefore, these data are best understood as a government’s intention to support media development, not a definitive accounting of how such funds were spent. Second, the data do not provide insight into the effectiveness of specific development interventions. Understanding the efficacy of individual projects would require much more detail about each specific project, its objectives, and metrics on what it was able to achieve. Instead, findings in this report represent the equivalent of a satellite image—they illustrate very broad trends in the overall funding environment.

And lastly, the figures reported to the OECD are enormously problematic. Previous CIMA studies have sought to explicitly break down funding by OECD DAC budget codes,78 but donors’ self-reported numbers may not necessarily match up. As one donor with USAID said: “We have a data problem. Over the years I’ve given different figures [to the OECD] because I don’t know where to look [in the USG records].”79

To report to the OECD, donor agencies must collect and standardize information that may be spread across several government agencies or bureaucracies, such as the foreign ministry, aid/assistance ministry, defense ministry, and so on. Frequently, the information captured as ODA may leave out significant sources of media development funding, including defense funding, for example, which may be used to support media as part of counterterrorism information campaigns. Some donors may include development communication (using media primarily to accomplish development aims rather than seeking to strengthen the media sector itself) and content production in their media assistance figures, while others may not. Indeed, many of the representatives from donor agencies who participated in this study admitted that neither their agencies nor even their governments could put a reliable or precise figure on what they spend on media assistance.

This problem is widespread and is a substantial roadblock in understanding the trajectory of aid to media development since the field’s inception.

For instance, donors themselves are split on whether support for international public broadcasters should be considered ODA. Some donors—Germany, the United Kingdom, and France—report this support as ODA to the OECD, while others do not. Because there is a lack of consistency in reporting, as well as a lack of consensus among donors, support for international public broadcasters is not included in this analysis except where specifically mentioned.

Qualitative Analysis

Twenty- six representatives of bilateral development donor agencies and implementing INGOs were interviewed between July 2022 and October 2022. The OECD DAC donor countries selected for analysis were Denmark, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.80 Representatives of two intergovernmental bodies were also interviewed—the EU, represented by NGO Media4Democracy, and the OECD, represented by a policy analyst working with the DAC.

The INGOs interviewed were selected to represent the main or largest media development implementers for their countries, such as CFI in France and BBC Media Action in the United Kingdom.81 A global INGO, the Global Forum for Media Development, was also included. The perspectives of these INGO representatives—most of whom are either chief executive officers or hold senior posts—are insightful because these representatives also often act as advisors to their government’s development agency, in many cases possessing much more experience and expertise in media support. This relationship is often critical to effective support, as many agencies lack dedicated media development experts.

Interviewing INGO representatives as well as donors helped fill the data gaps that exist in the OECD DAC database. However, it is important to note that representatives of INGOs are biased in some ways. For example, they may exaggerate their influence on bilateral donors and may see media development exclusively through the prism of their own specialization, such as media in conflict zones or the human rights of media workers.

Additionally, it was difficult to identify officials within bilateral aid agencies with knowledge of aid flows to media projects. This is mainly because support to independent media does not usually have a single home within an agency but will appear in various policy areas such as “governance,” “communications,” and “human rights” as well as “digital” or “infrastructure.” It is rare to find a “media desk” within a bilateral agency, and even rarer to find individuals with sufficient institutional memory to look back over 10 or more years.

Another caveat must be made about officials interviewed who represent donor government ministries. These people, too, invariably have an inbuilt bias in favor of media assistance, and media’s importance to democratic governance. Sometimes this means these individuals are at odds with their own hierarchy and do not necessarily share the political outlook of their ruling party or foreign minister. Often, they are trying to guess the future policy directions of their own ministry and can therefore find it difficult to predict funding levels.

Acknowledgments

This report came together through the support of several contributors. Coral Milburn-Curtis conducted in-depth quantitative analysis of the data. Don Podesta provided invaluable editorial support. Samuel Brazys and Alex Dukalskis at University College Dublin led the data collection and coding process with support from Daniel O’Maley. Sasha Schroeder helped facilitate interviews.

Footnotes

- Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2022 (Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2022), https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/FIW_2022_PDF_Booklet_Digital_Final_Web.pdf.

- Anya Schiffrin, “Media Capture in the Digital Age,” Center for International Media Assistance, June 17, 2021, https://www.cima.ned.org/blog/media-capture-in-the-digital-age/.

- “Official Development Assistance,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), n.d., https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/official-development-assistance.htm, accessed December 6, 2023.

- Shuhei Nomura, Haruka Sakamoto, Aya Ishizuka, Kazuki Shimizu, and Kenji Shibuyab, “Tracking Sectoral Allocation of Official Development Assistance: A Comparative Study of the 29 Development Assistance Committee Countries, 2011-2018,” Global Health Action 14, no. 1 (2021), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8032342/.

- “Summit for Democracy Summary of Proceedings,” The White House, December 23, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/12/23/summit-for-democracy-summary-of-proceedings/; “Summit for Democracy 2023,” US Department of State, n.d., https://www.state.gov/summit-for-democracy-2023/#OfficialEvents, accessed December 6, 2023.

- “Member Countries,” Media Freedom Coalition, n.d., https://mediafreedomcoalition.org/who-is-involved/member-countries/#, accessed December 6, 2023.

- Changes to CIMA’s Methodology: A few changes have been made to the methodology since CIMA’s first analysis of data from 2010 to 2015 was released in 2018. To maintain a longitudinal analysis that included all years of the currently collected data, these changes were also applied to all the data going back to 2010 so that further analyses could be conducted across the entire dataset. The following modifications resulted in relatively minor overall changes:

– The analysis in this report is confined to data reported directly to the OECD’s CRS database. CIMA’s previous report also included data provided by AidData on ODA-like expenditures using its Tracking Underreported Financial Flows methodology.

– The current coding now includes only information technology (IT) infrastructure investment that is directly tied to news media. Generic investments in IT are no longer included in total media development figures. For example, investments in digital television networks to help countries adapt from the transition from analog to digital transmission are now included in the figures.

– Projects that governments labelled as “Media and free flow of information” in their reporting to the OECD, but for which no title or short description was provided to the OECD, are now included in total media development figures. Previously, CIMA excluded these projects as our analysis was based on the title and short descriptions of projects. While it is difficult to ascertain much about projects with such limited information, because governments labelled these projects as being related to “Media and free flow of information,” they are now being included.

- Martin Scott, Media and Development (London and New York: Zed Books, 2014), 75.

- Our analysis builds on prior research by CIMA. See previous report from 2018: Myers and Angaya Juma, Defending Independent Media.

- “Estonia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA),” OECD, n.d., https://www.oecd.org/dac/dac-global-relations/estonias-official-development-assistance.htm, accessed November 21, 2023.

- Aleksandra Galus, “What Is Media Assistance and (Why) Does It Matter? The Case of Polish Foreign Aid to the Media in Belarus and Ukraine,” Central European Journal of Communication 3, no. 27 (2020), https://journals.ptks.pl/cejc/article/view/210/143.

- Free Press Unlimited representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 20, 2022.

- Converged Statistical Reporting Directives for the Creditor Reporting System (CRS) and the Annual DAC Questionnaire (OECD, April 2021), https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/STAT(2020)44/FINAL/en/pdf.

- Euan Ritchie, Charles Kenny, Ranil Dissanayake, and Justin Sandefur, “How Much Foreign Aid Reaches Foreign Governments?” Center for Global Development, May 24, 2022, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/how-much-foreign-aid-reaches-foreign-governments.

- Ibid.

- Yasmin Ahmad, Emily Bosch, Eleanor Carey, and Ida Mc Donnell, “Six Decades of ODA: Insights and Outlook in the COVID-19 Crisis,” in Development Co-operation Profiles, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/5e331623-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/5e331623-en.

- A Changing Landscape: Trends in Official Financial Flows and the Aid Architecture (World Bank Group, November 2021), https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/9eb18daf0e574a0f106a6c74d7a1439e-0060012021/original/A-Changing-Landscape-Trends-in-Official-Financial-Flows-and-the-Aid-Architecture-November-2021.pdf.

- OECD representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 11, 2022.

- BBC Media Action representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 11, 2022.

- Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 7, 2022.

- Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 16, 2022.

- Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 29, 2022.

- French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs representative in an interview with Mary Myers, September 8, 2022.

- French Development Agency 1 representative in an interview with Mary Myers, October 12, 2022.

- United States Agency for International Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 13, 2022.

- French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs representative in an interview with Mary Myers, September 8, 2022.

- These are countries supported under the Japan International Cooperation Agency’s media support program since 2010 (not all of these countries are current, and the list is not exhaustive).

- Japan International Cooperation Agency representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 28, 2022.

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 19, 2022.

- US State Department representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 25, 2022.

- Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs representative in an interview with Mary Myers, September 16, 2022.

- French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs representative in an interview with Mary Myers, September 8, 2022.

- Ibid.

- Global Forum for Media Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, August 11, 2022.

- US State Department representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 25, 2022.

- French Development Agency 1 representative in an interview with Mary Myers, October 12, 2022.

- See the project’s home page here: https://techfordemocracy.dk/, accessed November 21, 2023.

- International Media Support representative in an interview with Mary Myers, August 11, 2022.

- United States Agency for International Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 13, 2022.

- See, for instance, BBC Media Action’s project in Asia to counter the COVID-19 “info-demic,” supported by the UK government: “Rumors, mis- and dis-information about the new coronavirus COVID-19, including false cures and how the disease is spread, have been described as an ‘info-demic’ by the WHO Director-General. They can be as harmful as the virus itself.” See “Communication to Counter the COVID-19 ‘Info-demic,’” BBC Media Action, n.d., https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/where-we-work/asia/bangladesh/h2h-covid-19/, accessed November 21, 2023.

- German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 19, 2022.

- Canal France International representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 7, 2022.

- Global Forum for Media Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, August 11, 2022.

- Canal France International representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 7, 2022.

- Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 29, 2022.

- German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 19, 2022.

- BBC Media Action representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 11, 2022.

- ORTM: Office du Radio et Television du Mali, Mali’s national public broadcaster.

- We believe the “new regime” referred to in this interview is that of 2020, but Mali has seen two coups in quick succession—one in 2020 and one in 2021, after suffering political turmoil and insecurity since 2012.

- French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs representative in an interview with Mary Myers, September 8, 2022.

- INGO representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 30, 2022.

- BBC Media Action representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 11, 2022.

- Ibid.

- Deutsche Welle Akademie representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 5, 2022.

- Japan International Cooperation Agency representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 28, 2022.

- United States Agency for International Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 13, 2022.

- Global Forum for Media Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, August 11, 2022.

- French Development Agency 2 representative in an interview with Mary Myers, October 17, 2022.

- International Media Support representative in an interview with Mary Myers, August 11, 2022.

- Canal France International representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 7, 2022.

- “Fact Sheet: Summit for Democracy: Progress in the Year of Action,” The White House, November 29, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/11/29/fact-sheet-summit-for-democracy-progress-in-the-year-of-action/.

- This is a public/private partnership between USAID and Microsoft: “USAID, Internews, and Microsoft Announce Public-Private Partnership to Develop Media Viability Accelerator,” USAID, March 27, 2023, https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/mar-27-2023-usaid-internews-and-microsoft-announce-public-private-partnership-develop-media-viability-accelerator. For the projected funding, see USAID’s June 2023 business forecast, row 84, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-06/usaid-business-forecast-2023-06-14.xls, accessed November 21, 2023.

- “RFI – Empowering the Truth Tellers to Counter Corruption,” Government Contracts and Bids, n.d., https://www.govcb.com/government-bids/RFI-EMPOWERING-THE-TRUTH-TELLERS-AND-NBD00159029191837448.htm, accessed November 21, 2023.

- “FY2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act H.R. 2471,” GovInfo, March 2022, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-117hr2471enr/pdf/BILLS-117hr2471enr.pdf; “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021: H.R. 133,” GovInfo, August 2020, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-116hr133enr/pdf/BILLS-116hr133enr.pdf; “FY2020 Further Consolidated Appropriations Act (LHHSED, AG, Energy Water, Interior, Leg. Branch, MCVA, State-For. Ops, T-HUD) H.R. 1865,” Congressional Research Service, n.d., https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1865/text, accessed November 21, 2023.

- United States Agency for International Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 13, 2022.

- Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs representative in an interview with Mary Myers, September 16, 2022.

- Free Press Unlimited representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 20, 2022.

- Media4Democracy representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 8, 2022.

- French Development Agency 1 representative in an interview with Mary Myers, October 12, 2022.

- Canal France International representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 7, 2022.

- German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 19, 2022.

- International Media Support representative in an interview with Mary Myers, August 11, 2022.

- See, for example, Kaamil Ahmed, “UK Foreign Office Rushed £4.2Bn of Aid Cuts, Official Audit Finds,” The Guardian, March 31, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/mar/31/uk-foreign-office-rushed-42bn-of-aid-cuts-official-audit-finds.

- Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 16, 2022.

- BBC Media Action Representative in an interview with Mary Myers, July 11, 2022.

- Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 29, 2022.

- Aid in 2021: Key Facts about Official Development Assistance (Development Initiatives, February 2023), https://devinit-prod-static.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/media/documents/Aid_in_2021_Key_facts_about_official_development_assistance.pdf.

- Shanthi Kalathil, A Slowly Shifting Field: Understanding Donor Priorities in Media Development (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, April 2017), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/slowly-shifting-field/; Mary Myers and Linet Angaya Juma, Defending Independent Media: A Comprehensive Analysis of Aid Flows (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, June 2018), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/comprehensive-analysis-media-aid-flows/.

- United States Agency for International Development representative in an interview with Mary Myers, June 13, 2022.

- We attempted to secure interviews with the Canadian government, but no one was available. We were able to interview the following government agencies: France – the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs and the French Development Agency (AFD); Germany – the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ); Japan – Japan International Cooperation Agency (JIKA); Netherlands – Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Sweden – Embassy of Sweden, Pretoria, South Africa, and Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); Switzerland – Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC); United Kingdom – Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO); United States – United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and United States Department of State.

- There are other NGOs and INGOs that are implementing media projects, of similar size and standing, in our target countries.