Key Findings

Despite the explosion of digital news outlets globally, millions of people in sub-Saharan Africa continue to rely on radio as the most accessible independent news source. However, radio stations across the continent are facing unprecedented threats to their sustainability due to weak media markets, limited advertising revenue and intense competition. A more pragmatic understanding of viability and more flexible donor strategies can help these outlets stay on air and maintain their independence.

– Station managers must continually balance editorial independence, financial sustainability, and their mission to serve the public. Addressing these three challenges is not always compatible, and trade-offs are often inevitable.

– Successful stations are able to harness viable funding modalities without selling out and capitalize on management and operations techniques to expand reach

without compromising quality content.

– Marginal improvements in the flexibility of media donors and the media assistance community can foster greater viability and independence for small outlets in challenging context.

Introduction

When it comes to evading censorship, reaching mass audiences, and overcoming sometimes-costly barriers to entry, digital delivery seemed to offer a panacea to the journalists and news outlets covering local news. But the shift to digital has brought its own substantial challenges, and in much of the global south, online alternatives have yet to overtake the time- tested mass medium: local radio.

This is particularly true outside urban or wealthier communities, where populations lack consistent internet access. Here, radio continues to survive, if not thrive. What’s more, some outlets persevere without finding themselves beholden to either local politicians or international donor funding. The approaches they have taken toward sustainability offer critical insights for both struggling outlets and the organizations who look to support them.

In 2017, nearly 40 media professionals from across sub-Saharan Africa gathered to discuss the challenges facing independent media and propose collaborative solutions. They identified failing business models as the most significant obstacle to media pluralism in the region, exacerbated by limited advertising markets.1 Add to this the intense competition among media outlets, digital disruption, and governmental interference, and surviving as a local or community radio station can be a monumental struggle.

To explore this challenging environment, we decided to take a deeper look at the state of local radio in sub-Saharan Africa. Our eight primary case studies, while not an exhaustive sample, provide lessons from media outlets operating in even the most difficult circumstances.We identified the eight outlets, four each from Uganda and Zambia,as representative local or “proximity” stations with a public service mission. “Proximity radio” is a term borrowed from the French“radio de proximité,” which encompasses all types of community, local, and/or vernacular radio stations, profit or nonprofit, and are set up to serve a particular area and/or language group. Many such outlets focus on public interest content, often in far-flung rural districts or poor urban areas.

The eight case studies in this report include both community and commercial stations, but all have a public service remit. By that we mean their broadcasting sets out to improve people’s lives, be it through independent and/or local news, educational programs, public service announcements, social and behavior change messaging, or participatory program-making, offering a voice for the poor, marginalized, and disempowered. All are self-sustaining, with the exception of one donor- dependent outlet for contrast. Only two are based in capital cities, taking in the four corners of each country.

By investigating strategies on the ground and speaking with station owners and managers, we sought to challenge common assumptions about the nature of media sustainability. Specifically, how can local media houses with a public interest remit move toward financial security without losing their independence to either political pressures or significant donor subsidies?

The COVID-19 crisis that emerged in late 2019 has highlighted the critical role that radio stations like the ones studied here play in keeping communities informed worldwide. As this report was going to press, all the case study radio stations in Uganda and Zambia remained on-air with full programming, though in some cases with scaled-down staff due to curfews. All were broadcasting special shows and public health messages to help combat the virus.

Defining Sustainability: A Viability Perspective

Defining Sustainability: A Viability Perspective

International donors have increasingly recognized the role of news media and the crisis it now faces, and in turn moved to bolster and maintain independent voices around the world. Still, at just 0.3 percent of total official development assistance in recent years,2 these efforts face serious challenges of coordination, implementation, and sheer lack of expertise and resources. Donors’ constant question remains: “Is this project sustainable in the long term?” Absent outside support, would the market provide a sufficient source of income? Such questions are all the more significant for those on the ground working to be heard and, ideally, to be paid.

Beyond financial sustainability, however, is a more integrated approach to media viability. Deutsche Welle Akademie3 recently put forward a model for media viability that “looks beyond the money” at “a supportive legal environment, an equitable advertising market, journalism training institutions, professional associations, distribution networks, a reliable internet infrastructure, the trust of the community,” and more. The Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) similarly stresses the need fora holistic approach to media development, with a framework that encompasses the broader enabling environment.4

Drawing from these approaches, “viable outlets” here refers to those that are financially secure, are serving their audiences, and are editorially independent as an alternative to government media.

These stations are sufficiently professional and well managed such that they are likely to be thriving five years hence. Those that we consider “donor-dependent” would close or severely strip-down within a year if external donors stopped funding the station.5 Such donor support includes financial and other in-kind or training assistance provided by organizations (governmental, religious, charitable, or nongovernmental) based outside of the locality in which the outlet operates.

Methodology

This research is based on a review of current literature and an action-oriented study of eight proximity radio stations in Uganda and Zambia.

This research is based on a review of current literature and an action-oriented study of eight proximity radio stations in Uganda and Zambia.

The stations are Mama FM, Tembo FM, Speak FM, and Voice of Kigezi (VOK) in Uganda; Breeze FM, Phoenix FM, Radio Icengelo, and RadioMano in Zambia.

These are not necessarily representative of all proximity stations in sub-Saharan Africa,but the variety of sizes and business models highlights the range of approaches implementedin their drive for viability. Despite their differences, all eight are:

- Independent from government (privately or community-owned and controlled) and have survived as independent stations for at least five years.

- Not dependent upon grant funding, but instead financed substantially by advertising and/or other private sector support or commercial sponsorship. The only exception to this is Mama FM, which is trying to attract commercial advertising but is at present almost completely dependent upon grants and donor support.

- Operating under a social mission and/or public service remit.

Our teams spent just over two weeks in Uganda and 10 days in Zambia from August to October 2019. We visited each outlet for one to two days, interviewing each station’s owner,manager, financial and/or administrative officers, marketing staff, program managers, and producers. Other interviewees included market researchers, academics, and representatives of media support nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). At each station, we observed the day-to-day operations and analyzed a selection of news and other programs being broadcasted.

The Information Ecosystem in Uganda and Zambia

Recent years have witnessed a closing media space in both Uganda and Zambia, already historically poor performers in media freedom indices. Of the 180 states ranked by Reporters Without Borders in 2019, Uganda sits at 125, down eight points from 2018, and Zambia at 119, a steep drop from 72 just six years previously.6

Regardless, the dizzying changes that have swept media across the globe over the past 30 years have also made their mark for the better. Political and technological developments have brought huge growth in the number and variety of media outlets in both countries. In Uganda, for instance, the media sphere has boomed from little more than the single state broadcaster to 31 free-to-air TV stations, five digital satellite TV stations, more than 30 newspapers (print and online), and 258 operational FM radio stations.7 In 2019, around 44 percent of the population had mobile phone subscriptions, half of which were used to access mobile internet services.8 From near zero in the 1990s, internet access has soared to 46 percent of the population, though actual weekly internet usage is closer to 27 percent.9 As a result, radio has seen its audience share slowly diminish in favor of the internet,10 but not nearly enough to unseat it as the most utilized mass medium in both countries, particularly in rural areas.

Struggling economies, however, bring challenges for both outlets and audiences hoping to capitalize on this recent growth. In 2019, the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in Uganda and Zambia was $724 and $1,41711 respectively, which means that the public has very low purchasing power–even lower in rural areas, where most proximity radios are located.

Both governments wield enormous influence and dominate the advertising markets,12 which are limited to begin with given the two countries’ small economies. Drastic power shortages in both countries further strain the finances of television and radio stations, which incur the high costs of generators and fuel to stay on air.

In the face of financial hardships experienced by both media outlets and practitioners, corruption has become a feature of the media in both countries. The practice of brown envelope journalism, known as “blalizo” in Zambia and “facilitation” in Uganda, is an open secret. Journalists accept payment for news stories, often in the form of “transport” costs or other gifts, and, because the practice is so widespread, it slants reporting and news coverage in favor of those who can pay. These are often politicians and big companies, but it can also involve any individual or organization that wants their story covered, ranging from aid organizations and government ministries to statutory bodies like the police or electoral commissions. This inevitably introduces bias and partiality, especially in such a financially strapped environment, but typically only the better-endowed media outlets can afford to ban the practice altogether.

Official media regulation is in the hands of the Uganda Communications Commission and the Independent Broadcasting Authority in Zambia, neither of which are considered by human rights groups to be genuinely independent.13 Most rules governing indecency, bias, and hate speech are somewhat randomly applied and loosely enforced. Often, the regulations are instead invoked by the state as an excuse to send in police and close down a media outlet if it is seen to be biased in favor of an opposition party or candidate. Criminal defamation laws are used in both countries to stifle dissent. For most media houses, the choice often comes down to either appeasing the authorities by practicing self- censorship or ensuring they have other rich and powerful backers to protect them.

Radio Holds Strong as the Most Accessible Mass Medium

Despite the mobile and digital revolution, radio is still king in Uganda and Zambia. The latest figures (2018) show that in Uganda, 73 percent of the population tuned into radio at least once a week, compared to only 28 percent for television and27 percent online.14 Radio also remains the most accessible mass medium in Zambia, used by 67 percent of the population according to one 2018 estimate.15

In Uganda there are currently 258 FM radio stations, around 12 of which are classed as community stations.16 The government’s Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC) operates 10 radio stations17 and the rest are private. In Zambia there are currently 137 radio stations, 133 of which are private (either commercial or community radio stations), while four are publicly owned.18

Over half of the radio stations in Uganda and Zambia are small FM stations, which are often hybrids: community-type but not always with a community label. Given this, “proximity stations” remains the most accurate label. Breeze FM’s website, for example, claims the station “encompasses three kinds of radio: it is a community-based, commercial station, with public interest programming.”19

Almost all proximity radios face challenges of staff quality, high turnover, difficulties attracting advertising and sponsorship, and difficulties paying their personnel. Compared to other professions, pay is low for radio journalists in both countries.

As the following profiles demonstrate, all eight case study radio stations struggle to make a profit. Only three—Voice of Kigezi, Radio Icengelo, and Phoenix FM— can pay all of their journalists and presenters a regular wage and do not have to rely on volunteers.

Case Studies: Proximity Radio Stations Keep the Lights On

Map of Four Proximity Radio Stations in Uganda

Mama FM: “The voice to listen to,” 101.7 FM

Community radio station in Kampala, Uganda, established in 2001 by the Uganda Media Women’s Association

Community radio station in Kampala, Uganda, established in 2001 by the Uganda Media Women’s Association- 1 kW transmitter, reaching a radius of approximately 75 km, with an audience of 1.5 million listeners20

- 5:30 a.m. to midnight, seven days a week

- Broadcasting in Lugandaand English, the station concentrates on amplifying the voices of women in Uganda

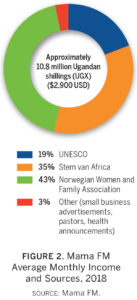

In 2018, the bulk of Mama FM’s revenue came from international donors, despite attempts to attract commercial advertising.All but two staffers are unpaid volunteers. In 2018,its annual income was roughly 130 million Ugandan shillings (UGX), around $35,000.

Tembo FM: “Voice for development,” 103.5 FM

Local/commercial radio station in Kitgum, Uganda, established in 2013

Local/commercial radio station in Kitgum, Uganda, established in 2013- 3 kW transmitter but only 1kW used currently, with a radius of up to 800 km and an audienceof 7–8 million when using 3kW, including listeners in neighboring South Sudan

- Broadcasting 24/7 in Luo, English, Swahili, and Arabic, the station covers a variety of content, with an emphasis on development issues.

Tembo FM’s income is a mix of advertising, paid-for talk shows, and the Lutheran World Federation (LWF). Its income in 2018 was roughly 235 million UGX ($63,941). In 2019, the station was, for the first time since its 2013 launch, able to raise almost all of its own revenue without falling back on its founder and financier, General Paul Lokech.

Speak FM: “Voices Unlimited,” 89.5 FM

Community radio station in Gulu, Uganda, established in 2012 by FOWODE (Forum for Women in Democracy)

Community radio station in Gulu, Uganda, established in 2012 by FOWODE (Forum for Women in Democracy)- 1 kW transmitter, reaching a radius of 80 km and an audience estimated (by the station itself) between 500,000 and 1 million

- Broadcasting in Luo and English, the station concentrates on gender equality and development issues.

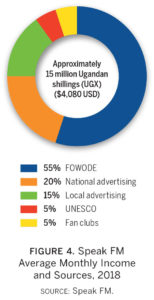

In 2018, just over half of its revenue came from its founding NGO, FOWODE. It also relies to some extent on volunteers. Its annual income is roughly 180 million UGX ($48,960).

Voice of Kigezi: “The Trumpet,” 89.5 FM

Local/commercial radio station in Kabale, Uganda, established in 1999 by independent businessman Ivan Mbabazi Butuma.

Local/commercial radio station in Kabale, Uganda, established in 1999 by independent businessman Ivan Mbabazi Butuma.- 3 kW transmitter with a 1 kW booster in the neighboring city of Mbarara, reaching a radius of 150–200 km and an audience of up to 3 million

- Broadcasting 24/7 in Ruchiga, Swahili, Ankole, and English, with a concentration on the Ruchiga-speaking community in the Kigezi region

In 2018, about half of its revenue came from advertising. Its total revenue in 2018 was approximately 400 million UGX ($108,700). It is the only one of the four Ugandan stations examined here to make a profit in 2018, which was about 20 percent.

Map of Four Proximity Radio Stations in Zambia

Breeze FM: “Lifting the spirit of the people,” 89.3 FM

- Local/commercial radio station in Chipata, Zambia, established in 2002 by private investor Mike Daka

- 1 kW repeaters at four relay sites in Eastern Province, reaching a radius of 300 km and an audience estimated at 1 million listeners

- 6:00 a.m. to midnight, seven days a week, followed by BBC live programs from midnight to 6:00 a.m.

- Broadcasting in Chinyanja and English, the station isa commercial radio with a community-based approach.

Financial details for Breeze FM were unfortunately unavailable, as at the time of our fieldwork and as this report was going to press, discussions were under way for the sale or transfer of the station to new owners.

Radio Icengelo: “The light of the Copperbelt,” 88.9 FM

Community radio station in Kitwe, Zambia, established in 1996 by the Catholic Diocese of Ndola

Community radio station in Kitwe, Zambia, established in 1996 by the Catholic Diocese of Ndola- 5 kW transmitter with repeaters in Ndola and Chingola, reaching a radius of approximately130 km and an estimated2 million listeners

- Broadcasting 24/7 in Bemba, Lemba, and English, the station aims to “evangelize, inform, educate, and entertain.”

In 2018, the bulk of its revenue came from advertising and paid-for programs. The radio station covers its costs but barely makes any profit. In 2018, its monthly income

was approximately 335,000 Zambian kwacha (ZMW) per month, and annual income roughly 4,200,000 ZMW, around $287,110.

Currencies converted at September 2019 rates.

Radio Mano: “Pride of the North,” 89.3 FM

Community radio in Kasama, Zambia, established in 2004 with support from Irish Aid

Community radio in Kasama, Zambia, established in 2004 with support from Irish Aid- 2 kW transmitter, reaching a radius of 200 to 250 km and an estimated audience of 900,000

- Broadcasting in Bemba and English from 5:00 a.m. to midnight, the station is a mix of music and talk shows on health, agriculture, politics, and religion.

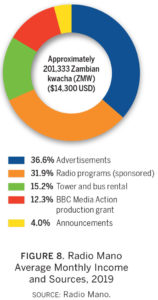

In the third quarter of 2019, the bulk of its revenue came from sponsored programs and advertising, with a sizeable proportion in a grant from BBC Media Action and from renting its tower. It also relies to some extent on volunteers. For July–September 2019,its budget was roughly 604,000 ZMW ($42,900).

Phoenix FM: “Only the best is good enough,” 89.5 FM

Commercial radio station in Lusaka, Zambia, established in 1996 by Errol Hickey, founder and major shareholder until 2015

Commercial radio station in Lusaka, Zambia, established in 1996 by Errol Hickey, founder and major shareholder until 2015- 100 kW transmitter, reaching a radius of 640 km and covering part of the Southern Province through Lusaka, Central and the Copperbelt Provinces and an estimated audience of 1.2–2 million per week

- Broadcasting 24/7 in English, the station presents a mix of news, education, information, and entertainment.

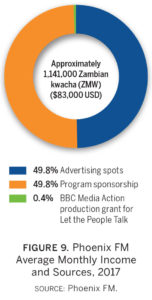

The bulk of its revenue comes from advertising and sponsorship. Its annual turnover for 2017was 13.7 million ZMW (approximately $1 million). Profit was about 10 percent of turnover.

Approaches to Supporting Sustainability

Proximity radio stations employ a wide range of strategies to survive, mapping out a diversified and pragmatic path toward viability. We grouped these strategies into three general approaches: fostering an enabling environment, harnessing viable funding modalities, and capitalizing on management and operations to expand reach.

Fostering an Enabling Environment

Fostering an Enabling Environment

Navigating Domestic Politics

Navigating national and local politics is an essential strategy for radio stations for two reasons: the government’s ability to close operations, and the government and politicians as a vital source of revenue. There are therefore constant and inevitable trade-offs, courting politicians on the one hand and maintaining editorial integrity on the other.

Almost all of our case study stations had stories of temporary closure or threats of closure by local or national authorities in the recent past as a result of landing on the wrong side of their governments. For example, at Radio Mano in 2016, nearly the entire newsroom was arrested and taken to court for allegedly insulting ruling party officials.21 Also in 2016, at Breeze FM, “We were barely 10 minutes into the program when the cadres started throwing stones at the station and making their way to the studio,” recalled Sam Zimba, station manager. “We had no choice but to sneak the opposition party leader out through a back door.”

Most of the station managers we spoke to were conscious of being watched and monitored by government. In Uganda, the station manager at the Voice of Kigezi (VOK) said, “State House listens to us all the time.” In Zambia, Phoenix FM staff reported that the Ministry of Information officials keep a close ear on their broadcasts: “Our biggest fear is that we might be closed due to a story falling foul of someone influential,” said News Editor Leah Ngoma.

Despite the state scrutiny, all of our case study stations saw it as their mission to hold leaders to account and ensure opposition voices had the opportunity to be heard. Still, they knew they couldn’t go too far. For example, VOK Station Manager Andrew Agaba said, “We try to call out corruption, and we’re the only radio station that hosts the opposition in the area, as well as the president and ruling party. We’re lucky to be owned by a businessman. We’re not [politically] affiliated.” Yet, he added, during the last general elections in 2016 an opposition party had booked time to explain its campaign. “Fifteen minutes into the program, the police came and asked us to shut down, so we did.” As a result, self-censorship has become the norm.

Government departments and individual politicians also wield power as a vital source of income for radio stations, particularly during election campaigns for local and other offices. As Phoenix FM Programs Manager Luciano Haambote remarked, “During elections, money talks—we want to find a balance but there is a tension between sales and programs. Those [politicians and political parties] that will pay go on-air, those that can’t won’t get on air.”

This paid airtime is typically either straightforward advertising or more subtly framed as a talk show. Talk shows are usually live variety-format broadcasts, with music, interviews, call-ins, news bites, games, and spot advertisements paid for by one or more entities. In instances where the guests have paid to appear on the show, the presenter could be given an agreed upon list of questions in advance. Formats vary and can include call-ins from listeners, but normally the discussion is almost completely controlled by the guest.

A significant proportion of the income reported by our case studies is generated by such talk shows. They make up 20 percent of revenue at VOK, for instance, and paid-for programming constitutes almost a third of income at Radio Icengelo.

Although the inclusion of such content might be seen as compromised journalism, several of the stations argue that they are able to balance the paid-for talk shows with their own editorially independent shows,for which no payments are involved. These, they say, are much more impartial. For example, at Phoenix FM, a flagship program Let the People Talk is aired twice weekly with one edition per week supported by BBC Media Action. It is a live, two and a half-hour talk show with invited (nonpaying) guests, including government representatives, who answer questions from listeners.

Stations that have sufficient staff also strive to protect journalistic integrity through strict separation of business operations and production. The accountant at Tembo FM, Monday Okello, said: “Journalists can easily be compromised by the politicians, so we try to ensure that Charles [the marketer] or I sell airtime, rather than the journalists.” Financial realities, however, make such clear delineations within the newsroom difficult for stations often already reliant upon volunteers.

National and local government are also important advertisers, as are parastatals.22 For instance, at Radio Icengelo, among the largest clients are the Zambia Revenue Authority, Kitwe City Council, the National Pension Scheme Authority and Zamtel, a government-owned telecommunications company. However, government advertising can be awarded or withheld at whim. As PEN Zambia Center President Nicholas Kawinga observed, “Government can influence private companies to take away advertising from media houses that are out of favor.”

In a cash-strapped environment, then, having well-placed political friends is important for both political protection and as a financial cushion. We found a closeness to government, ruling party, or a powerful opposition politician behind almost all of the radio stations we studied. At Tembo FM, the owner is a former general in the Ugandan army, though he stressed that he remains completely apolitical. Speak FM is backed by an NGO headed by the wife of the main opposition leader, Kizza Besigye. The managing director of Phoenix FM claims not to be politically connected but has “friends.” Similarly, the businessman at the head of VOK is not overtly politically affiliated, but his business partner is the executive director of the Uganda Communications Commission, thereby wielding a great deal of influence and protection for the station.

Utilizing Donor Support—Within Reason

Utilizing Donor Support—Within Reason

Financial support from donor grants, while offering an alternative to navigating domestic politics, inevitably comes with its own trade-offs. Just as we focused on politically independent radio stations, we also intentionally chose stations that were not heavily dependent upon donor support. Mama FM is the one exception to this, presenting a contrasting case as it remains almost entirely financed by donor funds, despite its efforts to attract advertising.

Nonetheless, we found that donors played a role in the finances of all our case study stations to some degree. Bigger grants normally come in a package, including training, equipment, and other support for the station. For example, UNESCO supported Speak FM with a package of information and communications technology (ICT) equipment and training; the Lutheran World Federation launched a large sponsorship for Tembo FM of up to four hours of airtime per day, specifically targeting a nearby refugee camp; and Phoenix FM, Breeze FM, Radio Mano, and Radio Icengelo all receive training, business management advice, and/or grant support for a specific production.

Again, there are trade-offs involved with accepting donor funding. One issue is the danger of surrendering content control to the donor. As paid programming from local actors can sway coverage, so too can program-specific grant-making, particularly if it makes content demands on an already limited staff. Beyond content control, the station must also weigh the opportunity cost. Regularly applying for grant funding requires time and personnel in both preparations and in building and maintaining a relationship with the donor, in addition to writing reports and accounting.

Still, the greatest risk is donor dependency. Monica Chibita, dean and professor of Mass Communication at Uganda Christian University, explained: “Quite often stations become dependent, and without good governance, people [at the radio station] can lose the will to plan—so some are closed down, some are limping.”

Harnessing Viable Funding Modalities

Harnessing Viable Funding Modalities

Commercial Advertising

As the economic profiles above show, radio stations do not necessarily make distinctions between the private sector, the public sector,and nonprofit organizations. From a radio marketer’s perspective, advertisers can just as well be a political party, a parastatal, an aid agency, or a commercial entity. In practice, the definition of advertising is very blurred.

All the station managers and owners in our study were interested in finding advertising revenue from commercial companies, though some more than others. For VOK, for instance, all of the staff are expected to act as marketers, a marked difference from Tembo FM’s clear separation of journalists from business operations.

Companies advertising on our case study stations include the big telecommunications companies such as Zamtel, Airtel, and MTN, multinationals like Unilever and Pepsi, banks like the Bank of Zambia and Stanbic, as well as smaller, local enterprises including water/ sewerage companies, hotels, schools, and agricultural firms.

While advertising revenue is needed and highly sought after, it is not without its disadvantages. Undue corporate influence is potentially an issue for all would-be independent radio stations. At religious radio stations like Radio Icengelo, station policy often prevents running ads that promote condoms, gambling, cigarettes, and alcohol.

Some stations secure sponsorship for their websites and/or sponsorship of a regular show, such as the news or a daily program like a sports round-up or the weather forecast. At Breeze FM, even some of the news bulletins are sponsored, which again raises impartiality issues, though the station manager insisted, “This does not make the sponsor immune to coverage, good or bad, and we make that very clear in our contract.”

In the drive for advertising revenue, our case study stations had the following in common:

- The majority of advertising revenue comes from the capital city,not the station’s immediate locality. For example, at Radio Mano, only 5 percent of advertising comes from the local town, Kasama, whereas 80 percent is from Lusaka and the remaining 15 percent comes from outside of Zambia through agencies. Similarly, in Uganda, 80 percent of overall ad-spend is centered on Kampala and the Central Region, despite the fact that 75 percent of radio stations are outside Kampala and 76 percent of the population reside outside Uganda’s Central Region.23

- Government departments running public awareness campaigns make up a large proportion of the advertisers, especially for proximity radio. At VOK, for example, government takes the lion’s share, followed by NGOs and international agencies, then telecommunications companies and consumer goods.

- Having at least one, if not several, marketers on staff helps generate income. Phoenix FM’s sales department has four full-time staff and one marketer targeting local small and medium enterprises. Radio Icengelo has nine full-time marketing staff and four sales representatives. All but Mama FM have at least two dedicated marketers.

- Each station has creative and diverse ways of featuring advertising and sponsorship. For example, DJs are often paid to mention a product or service a set number of times during their show, or stations run a product placement in dramas and skits.224

- All radio stations have difficulties getting advertisers to pay on time, and some even employ debt collectors. “The big boys don’t pay on time,” said the station manager at VOK, meaning the telecommunications and drinks companies, whereas government ministries like the Ministry of Health more frequently paid on time and through electronic transfer. At Phoenix FM, advertising agencies can take more than 60 days to pay and debt collectors take a commission on debts collected, as do sales staff.

- Stations are often forced to abandon their standard prices for spots, messages, and sponsorship because of competition from other media. “Our rate card is unfortunately very flexible,” said Andrew Agaba, station manager at VOK. To counter this, stations can appealto advertising agencies or individual agents to bring in business—but they almost always have to pay kickbacks to agents or give discounts to advertisers. Stations in Zambia appear particularly dependent upon advertising agencies, which help bring in business (in most cases for commercials already produced and ready to air) but offer rates much lower than the standard.

Market Research

Market Research

Large audience numbers are vital to selling advertisements. The Paris- headquartered IPSOS is the pre-eminent market-research companyin both Uganda and Zambia, and almost all the stations we spoke to depend on IPSOS ratings to demonstrate their reach. Additionally, IPSOS provides a service to media outlets which monitors the ads they play. This allows stations to prove to advertisers that their commercials are broadcast as contracted. Though they all referred to those surveys and ratings, only two of the eight case study stations, VOK and Phoenix FM, could afford to pay IPSOS25 for its monitoring services. Other Zambian stations benefited from research commissioned by BBC Media Actionor IPSOS reports being made available to them for free (though not always immediately).

Some concerns were expressed about sampling biases: for example,a Phoenix FM representative said that IPSOS’s methodology, using daytime household-based face-to-face interviews, does not pick upcore segments of the station’s audience who are male, middle class, and employed. There were hints of corrupt practices: at one station in Uganda, the station manager (who did not wish to be named) cited calls from IPSOS agents who sought out bribes in return for higher ratings. On the other hand, some within IPSOS alleged that sometimes media owners try to bribe field researchers to skew the audience numbers in their favor, although an IPSOS representative in Uganda told us that safeguards are put in place so that media owners rarely succeed.26

In addition to attracting advertisers by sheer numbers, audience research also allows for more strategic placements. Segmenting a station’s audience, for instance, can identify key groupings, such as farmers or young mothers, and attract specific, niche advertising.

Syndicated Advertising Revenue

In both Uganda and Zambia, we came across efforts by internationally funded agencies to help public-interest radio stations work together and take better advantage of the available advertising. In Uganda, the East Africa Radio Advertising Service (EARS) is helping proximity stations to bargain collectively for a bigger share of the advertising market and for better service and rates. Requesting a 20 percent commission, EARS is acting as a social enterprise with seed funding from a German nonprofit organization, Media in Cooperation and Transition (MICT).27 In Zambia, BBC Media Action has attempted to help proximity stations bargain collectively with advertising agencies through a loose association called the Zambia Radio Marketing Network. The idea was to appoint an agent to represent a group of 19 affiliated stations who would take 16 percent of sales (ad agencies typically take a much higher rate of 45 percent).28 EARS began in October 2019 so will be one to watch with interest. The BBC Media Action effort, however, has suspended activities for the time being after the Competition Commission in Zambia, a competitor of Zambia Radio Marketing Network, deemed the latter a cartel.29

Community Announcements

Announcements by listeners are often the backbone of proximity radio, from song requests to announcements of births, christenings, marriages, and deaths. All the stations we spoke with broadcast interactive programs and some paid announcements, but VOK is especially effective: listeners’ messages each earn the station 10,000 UGX ($2.70) and make up 25 percent of the annual revenue of the station, earning a total of about 100 million UGX (approximately $27,000). These announcements fill up to two hours of airtime per day. This relatively high contribution to income is likely to be a product of the station’s large reach and strong community identity.

Talk Shows

The term “talk show” refers to live or pre-recorded programs in which guests pay to appear. Sometimes they feature political candidates (as outlined above) but the more regular clients are government ministries, parastatals, and NGOs, who buy airtime ostensibly for the purposes of raising audience awareness about issues of public interest, from tax evasion to education. These are often 30-minute or one-hour programs, during which the client will answer an agreed upon set of questions before listeners can call in with further questions or comments. However, the content can easily be skewed to the particular agenda or product that the sponsor is promoting. Companies can also pay for a 30-minute talk show as they would for a spot commercial (per minute and per time of day). For instance, a Chinese company buying cassava in Zambia and an herbal doctor selling natural medicines in Uganda both paid for such shows.The local radio station provided a moderator while the interviewees “explained”—or “sold”—their services or products. The extent to which these shows are properly signposted varies greatly. Sometimes the audience will be alerted ahead of time that a talk show has been paid for by the client, but sometimes not.

Other Income-Generating Initiatives

Several stations have sought to lessen their dependence on advertising by diversifying their revenue streams. For example, Radio Mano sells peanuts, hires out a bus, and manages a pine tree planting project. However, these kinds of income-generating activities rarely, if ever, are big moneymakers: in the case of Radio Mano, peanut sales generate just 0.02 percent of its annual income. Fundraising among the community is also sometimes cited as a good strategy for proximity stations, but of the stations examined here, only Radio Mano, whose listening clubs have occasional fundraisers, drew on the local community as a source of donations.30

Bailouts from Benefactors or Founders

In a worst-case scenario, proximity stations also frequently rely onan individual or an organization to bail them out. For VOK, it wastheir founder who shifted money from other parts of his business; for Speak FM, it has been the founding Ugandan women’s NGO, FOWODE, a dependable benefactor since the outset. Phoenix FM’s founderErrol Hickey had other businesses that cross-subsidized costs in the early days. With significant aid support from Norway, the station literally rose from the ashes twice after fires destroyed most of its assets in the 1990s.31

Part of being sustainable as a station is being able to weather storms, and almost all of our case study stations have passed through difficulties at some time or another. Unless they have a reliable cushion of some kind, most proximity radio stations are often just one unexpected bill away from financial ruin.

Capitalizing on Management and Operations

Capitalizing on Management and Operations

This final section looks at the third challenge for local radio stations: maintaining and expanding reach without compromising quality content. Serving the audience and promoting development are the core missions of proximity radio, as was emphasized repeatedly by the station managers and owners we interviewed. All had positive stories to tell. News Editor Patrick Kabwe at Radio Mano, for instance, confirmed, “We have helped speed up development,” citing an in-depth report on challenges for a local school that prompted the relevant authorities to take action.

For all of our case study stations, keeping and expanding the audience was recognized as a vital and ongoing task, both for their mission and for their longevity. If you’re popular, you are beating the competition, and if you have a large reach, your airtime has more monetary value.

Investing in Good Business and Financial Management

Investing in Good Business and Financial Management

Whether for commercial or nonprofit stations, investing in good business and financial management provides a clear advantage for station longevity. In the case of Phoenix FM, the station is now profitable for its current owners after early years of greater donor dependence.

Investing time in staff training for marketing and business management was mentioned by all four of our Zambia case studies, less so in Uganda. At least five of our cases had previously participated in similar courses offered by NGOs.32 Where the sales and marketing operations were already quite efficient, like at VOK, the stations did not express a desire for further support. By contrast, those struggling to attract advertising, such as Mama FM and newer outlets such as Speak FM, indicated they would like training in marketing.

For some station managers, having a supportive governing board was also crucial, with those identifying as community stations, like Mama FM and Radio Mano, very proud of their community-elected boards and horizontal structures. One media expert suggested, “When it comes to political pressures, a board will defend content if well constituted— weak boards can be influenced and content diluted.”33 By contrast,a more top-down structure seems to have worked for larger stations like Phoenix FM and Radio Icengelo, which both have active boards constituted like corporate entities with highly professional members. The owner of VOK offered yet another view, saying he felt a board “would slow me down.”Keeping and expanding the audience was recognized as a vital and ongoing task, both for their mission and for their longevity. If you’re popular, you are beating the competition, and if you have a large reach, your airtime has more monetary value.

Relying on Volunteers

Almost all of our case study radio stations had unpaid volunteers among their staff. In the case of Mama FM, all but the station manager are volunteers; at Speak FM there are 18 staff, 14 paid and four volunteers. From a radio manager’s point of view, volunteers help significantly in cutting salary costs and are an important way of involving the community and providing substantive experience to would-be journalists. However, while volunteers can help a radio station survive in the short term, relying on volunteers is not a long-term sustainability strategy—and in fact, it can undermine the professionalism and appeal of a station. Volunteers tend to be young, inexperienced, untrained, and impermanent. Volunteer reporters may also be more tempted to accept “brown envelopes” for the sake of financial expediency, which potentially harms the reputation of the radio station they work for. Bigger, richer stations such as Phoenix FM, Radio Icengelo, and VOK are able to pay almost all their staff a regular and decent salary, allowing them to retain quality personnel and build up a loyal listenership.

Sweating the Assets

Several of our case study stations are lucky enough to own their own premises and so do not have to pay rent, and such assets may even generate income. Donors endowed Mama FM, Radio Mano, and Radio Icengelo with their own premises at the outset. Some stations have other assets, such as a tower or grounds, which also allows them to draw rental income. Radio Icengelo, for instance, shares its tower with mobile phone companies and the station’s gardens are hired out and advertised on their website.

Others set up barter arrangements, so at Speak FM, for example, a local generator-servicing company benefits from free advertising in exchange for servicing the radio station’s generator on a regular basis.

Longevity and Powerful Transmitters

Stations need time to build up loyal audiences. The longest-running radio stations among our case studies were also the ones with the largest audience numbers, and it helps to have got in early, built up your audience gradually, and beaten the competition. VOK launched in 1999 and has since built an audience of up to 3 million, partly by starting with a powerful transmitter (3kW) before restrictions on transmitter strength were introduced (1kW is the current limit for new FM radio stations). VOK is now rated number one in the Kigezi region by IPSOS.34

Likewise, in Zambia, Radio Icengelo and Phoenix FM (both foundedin 1996) have built a strong audience over 24 years of operations. A recent survey showed that Radio Icengelo is the number one stationin the Copperbelt with an 85 percent market share; Phoenix FM was the first independent commercial FM station in Zambia and has since acquired five extra frequencies on an expansion program to the north.35

Integrity and Reputation

Integrity and Reputation

Radio station owners and staff want to be trusted by their listeners and to be seen as reliable sources of quality journalism. “My greatest fearis our news being rendered irrelevant by the communities we serve. Therefore, even when things are tough, we always remind each otherto be impartial and professional in our news coverage,” said Patrick Kabwe, Radio Mano’s news editor. Audiences also listen because they identify with a particular station and develop loyalty to that station’s brand. “Our brand is that we are a mature radio station with unique programs,” said Bertha Mabeti, a marketer at Radio Icengelo.

Station managers know that maintaining their station’s integrity is vital but also involves difficult choices. Responding to a question about financial pressures and journalistic ideals, Jane Angom, the station manager at Speak FM, said, “We do not want to trash our identity.We do not want to trade our editorial independence in our quest for looking for cash. We want to stay who we are and do what we need to do, and be able to get money to sustain the whole process.”

Knowing Your Audience

For radio stations to deliver relevant content, it is important to know who is listening. “Our typical listener is a married woman, 24 yearsold with two kids in a village 5 kilometers away from Kabale. She isa farmer and she is a religious person,” said Andrew Agaba, station manager at VOK in Kabale, Uganda. While keeping the typical listener in mind is useful, serving a whole geographical zone or language group also means having mixed content and ensuring that all segments of society that tune in are served. For example, Breeze FM sees its target audience as “10- to 70-year-old males and females, including young learners, students, peasant farmers, small-scale traders, workers, businessmen, and members of the general public.”

All our case study stations prioritize space for local language, news, and culture, and strive to keep programming live and interactive, funny, fresh, and entertaining. Featuring the voices of their community is vital and call-ins are a mainstay, as are listening clubs.

By and large, we found that the broader the appeal, the bigger the audience and the larger the revenue base. Smaller stations have to offer something different from the competition or find ways to appeal to a certain subsection of the population. For Mama FM, this means developing programs of special interest to women.

Another way to appeal to listeners can be by rebroadcasting news from international channels such as the BBC and Voice of America via specially installed satellite dishes. VOK does this and consequently attracts more advertising by topping the IPSOS ratings.

Going Digital

Going Digital

All eight case study radio stations have recognized the need to havean online presence, though some more than others. All of them have Facebook pages and use the platform to post written and sometimes video content, but only Phoenix FM and Breeze FM livestream their audio content. Phoenix FM, Breeze FM, and Radio Icengelo have their own websites and use them not only to reach new audiences but also to attract advertising.

We were struck by how few of the station managers we interviewed expressed anxiety about the internet as a competitor. Instead, they tended to be more concerned about the immediate competition from other local radio and TV stations. While online access is growing in Uganda and Zambia, especially via smartphones, it does not seem to be disrupting radio as much as might be expected. This is partly because internet access is concentrated in large urban areas and among the better-off, and proximity stations are generally in provincial areas witha higher proportion of less-affluent listeners. So the competition from the internet is not a burning issue, yet. Even then, it cannot deliver the localized content brought by familiar presenters and talk show hosts that radio provides.

Building on Success without Losing Sight of the Mission

It is a continuous and pragmatic balancing act. As our case studies show, proximity radio stations employ a wide range of strategies to survive. They must survive politically and financially, and keep and expand their audience while staying true to their social mission.

It is a continuous and pragmatic balancing act. As our case studies show, proximity radio stations employ a wide range of strategies to survive. They must survive politically and financially, and keep and expand their audience while staying true to their social mission.

While the case studies varied in many ways, two key lessons can be extracted from them all:

- Deploy a range of survival strategies. The mushrooming of radio stations in both countries has increased competition and driven down airtime rates. Even the biggest proximity stations cannot rely solely on longevity, reputation, and advertising. Our case study stations show a variety of survival strategies and it is not guaranteed that deploying them will result in long-term viability–but it is a necessary start.

- Retain a close sense of community but build a large audience. Radio stations must do all they can to expand their audience and tap into the national advertising market while remaining close to their community. The bigger radio stations we studied (Radio Icengelo, VOK, and Phoenix FM) show that it is possible to achieve financial sustainability through commercial revenue, and there is money to be found at the “bottom of the pyramid,” among the relatively poor. What matters, as far as selling advertising and airtime, is reaching as many consumers at the bottom of that pyramid as possible.

What does this imply for the media assistance community? Above all:

- “Perfect” may be the enemy of “good.” As our case studies demonstrate, financial survival often means allowing for less-than-ideal program design and implementation. In other words, it may be unfairto hold these struggling stations to an absolute gold standard, scarcely attainable in even the best circumstances. Overwhelming commercial and political pressures can sometimes mean that quality suffers or that programs may be compromised or less than perfect. Nevertheless, it should be celebrated that proximity radio stations are able to survive at all, made possible by journalists who remain committed despite enormous constraints. Perhaps it is time that the media assistance community accepts the “good” instead of the “perfect” for the sake of expediency, and opts for pragmatic viability instead of sustainability.

- There is a role for support and advice on paid-for content. In particular, such support should aim to improve signposting and clearly trail the programs and talk shows that are paid for by politicians and sponsors, differentiating them from content that is editorially free. This signaling often does not take place so, if done properly, would help make the distinction clearer for audiences and safeguard the reputations of the outlets involved.

- Outside funding is not necessarily the answer. As observers, we were impressed by the way the proximity radio stations we studied worked to uphold their editorial independence, make ends meet, and resist political pressure, in spite of a difficult economic environment where freedom of expression and information are still battles to be won. It is often assumed that outside or donor funding will protect proximity radio—and, indeed, public interest media in general. But our case studies show that donor partnerships and grant-funding do not necessarily allow a radio station to better serve the public interest and to stay above politics. This challenges some donor assumptions about how to foster good media content. On the contrary, donor fundingcan put proximity radios in a position of continuous donor-chasing, always cutting corners to save money and dependent on volunteers. Dependency on volunteers, in turn, lowers the professionalism of stations, makes them more vulnerable to the temptations of “brown- envelope journalism” and makes them more liable to put listeners off. And if you lose your audience, you gradually lose your station.

This research is published in collaboration with Media Support Partnership.

Acknowledgements

We thank our dedicated research team—Emily Arayo, Louis Davison, Mwendalubi Maumbi, and Martin Ssemakula—with special mention of Dr. Martin Scott of the University of East Anglia (UK), who made important inputs both to the research design and to the shape of this report. We greatly appreciate our many key informants—at Mama FM, Speak FM, Tembo FM, and Voice of Kigezi in Uganda, and at Breeze FM, Radio Icengelo, Radio Mano, and Phoenix FM in Zambia—who welcomed us to their radio stations. Thanks also go to all of our other interviewees who gave us their time and insights and to Paul Kavuma, Simon Davison, and Sam Muyonga.

Finally, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to the trustees of Media Support Partnership, sister organization of iMedia Associates, and especially Gavin Anderson, and Gordon Adam whose work on media markets was the original inspiration for this work and who made available a significant grant to support our research costs.

Footnotes

- Benequista, Nicholas and Herman Wasserman, 2017,Pathways to Media Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: Reflections from a Regional Consultation (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance), https://www. cima.ned.org/publication/pathways-to-media-reform-in- sub-saharan-africa/.

- Myers, Mary and Linet Angaya Juma, 2018, Defending Independent Media: A Comprehensive Analysis of Aid Flows (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/ comprehensive-analysis-media-aid-flows/.

- Deselaers, Peter, Kyle James, Roula Mikhael, and Laura Schneider, 2019, “More than Money: Rethinking Media Viability in the Digital Age,” Deutsche Welle Akademie, https://www.dw.com/en/more-than-money-rethinking- media-viability-in-the-digital-age/a-47825791.

- Center for International Media Assistance, “Media Development: Sustainability,” https://www.cima.ned.org/ what-is-media-development/sustainability/.

- We recognize that this is an imprecise statement: much depends on the stations’ own judgement of their viability. By “donor,” we exclude local sources of finance from our meaning, for example philanthropic donations by local business people, which we classify as community funding.

- Reporters Without Borders, 2019, “Ranking 2019,” https:// rsf.org/en/ranking.

- CIA, “The World Factbook: Uganda,” https://www.cia.gov/ library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html; Onlinenewspapers.com, “Ugandan Newspapers,” http:// www.onlinenewspapers.com/uganda.htm.

- GSMA, 2019, Uganda: Driving Inclusive Socio-Economic Progress through Mobile-Enabled Digital Transformation (London: GSMA), https://www.gsma.com/ mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ GSMA_Connected_Society_Uganda_Overview.pdf.

- IPSOS 2018 figures show 27 percent of the population access the internet at least once a week. See Godwin Asiimwe, Ipsos research director, personal communication, Kampala, September 2019.

- For example,in Uganda, listening to radio has declined from 95 percent of the population in 2014 to 73 percent in 2018. See Godwin Asiimwe, Ipsos research director, Kampala, personal communication, September 2019. By contrast, internet usage is the only media on the rise in terms of daily usage—up from 16.9 percent usage in 2014 to 23.7 percent usage in 2017. See World Bank Data Bank, https://databank.worldbank.org/reports. aspx?source=2&series=IT.NET.USER.ZS&country=.

- International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019,” https://www.imf.org/external/ pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/index.aspx.

- MISA,2017,African Media Barometer:Zambia2017 (Windhoek, Namibia: Media Institute for Southern Africa and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung), https://library.fes.de/pdf- files/bueros/africa-media/14071.pdf.

- Article19,2017,“Uganda:BanonLiveCoverageLimits Access to Information,” October 3, 2017, https://www. article19.org/resources/uganda-ban-on-live-coverage- limits-access-to-information/; Reporters WithoutBorders, 2019, “Zambia: Outspoken Zambian TV Channel Suspended for 30 Days,” March 12, 2019, https://rsf. org/en/news/zambia-outspoken-zambian-tv-channel- suspended-30-days.

- IPSOS, figures for 2018. See Godwin Asiimwe, Ipsos research director, personal communication, Kampala, September 2019.

- BBCMediaAction,2018,How Support to Local Radio Can Empower Social Change: A Case Study from Zambia (London: BBC Media Action), http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/ mediaaction/pdf/research-summaries/zambia-research- summary-web-final.pdf.

- UNESCO,“Empowering Local Radios with ICTS:Uganda,” https://en.unesco.org/radioict/countries/uganda.

- The Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC) runsBuruli FM, Butebo FM, Magic100 FM, Mega FM, Ngeya FM, Star FM, UBC Radio, UBC West, Voice of Bundibugo, and West Nile FM.

- CIA,“The World Fact Book: Zambia,”https://www.cia.gov/ library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/za.html.

- Breeze FM Chipata ,http://breezefmchipata.com/.

- The four Ugandan radio stations based their estimates on research conducted by IPSOS (in some cases on behalf of BBC Media Action) unless otherwise noted.

- Committee to Protect Journalists, 2016, “Zambian Police Arrest Five Radio Journalists,” December 5, 2016, https://cpj.org/2016/12/zambian-police-arrest-five-radio- journalists.php.

- A parastatal is “a company or organization which is owned by a country’s government and often have some political power.” See Cambridge Dictionary, “Parastatal,” https:// dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/parastatal.

- Douglas Mutumba, EARS (East African Radio Advertising Service), personal communication, Kampala, 2019.

- Godwin Asiimwe, research director, IPSOS, personal communication, Kampala, 2019.

- IPSOS monitoring fee is up to 8million UGX (approximately $2,137) set up fee then 1 million UGX (approximately $267) every month. Godwin Asiimwe, research director, IPSOS, personal communication, Kampala, 2019.

- Godwin Asiimwe, Ipsos research director, personal communication, Kampala, September 2019.

- Douglas Mutumba, EARS (East African Radio Advertising Service), personal communication, Kampala, 2019; MICT, https://mict-international.org.

- Interview conducted with BBC Media Action personnel, September 11, 2019.

- Soren Johannsen, country director, and Boyd Chibale, project manager, BBC Media Action, personal communication, Lusaka, 2019.

- Jallov, Birgitte, 2012, Empowerment Radio: Voice Building a Community (Gudhjem, Denmark: Empowerhouse); Fairbairn, Jean, 2009, Community Media Sustainability Guide: The Business of Changing Lives. Internews, https:// internews.org/resource/community-media-sustainability- guide-business-changing-lives.

- Errol Hickey died in February 2017, his daughter Joanna sits on the board of Phoenix FM.

- Errol Hickey died in February 2017, his daughter Joanna sits on the board of Phoenix FM.

- Author interview with Chibamba Kanyama, journalist/ economist, Zambia.

- Godwin Asiimwe, research director, IPSOS, personal communication, Kampala, 2019.

- This figure was cited by the station based on the research commissioned by BBC Media Action