Key Findings

Private foundations and official donors are beginning to recognize their role in a global effort to preserve independent, professional journalism. Amid a series of complex threats to quality news and information, the providers of international assistance are currently deliberating new collaborative efforts.

Shall they join forces to create a new global fund, something to buttress the ailing news industry as The Global Fund for Tuberculosis, Malaria and Aids has done for health systems? Shall they focus their support on knowledge, research, and learning amid all of the uncertainties created by fast-evolving digital communication technologies? Or shall they instead direct their support towards assembling the networks and coalitions that can fight for the fundamental reforms needed to enable professional journalism to thrive?

This report, the last in a series that has explored entry points for strengthening international cooperation in the media sector, sheds some light on these questions. Based on 27 interviews with representatives of both private and official donor agencies, it examines the major obstacles and stumbling blocks that will have to be avoided if global support to the media sector is increased.

The institutional impediments to effective aid, the report finds, are frequently related to limited human capacity and expertise in media at the donor organizations and a misalignment of support and needs. The cross-donor collaborations currently being considered can help to address these shortcomings, though not without risks. The report offers some important points for donors to contemplate as they collaborate to support international media development.

Introduction

At a perilous time for the news media in countries across the world, international donors are asking themselves if they can do more to help. A slew of proposals—from a global fund for public interest media to local initiatives designed to shore faltering news organizations—seek to address what has been called the biggest crisis in independent journalism since the 1930s.

Both private foundations and official donors increasingly see a role for philanthropy in the world’s news media ecosystem. How can this support be structured and delivered in an effective way? What lessons have donors learned from their many years of media development work? What new approaches and donor practices are needed to address the current crisis?

This report is part of a series exploring how to strengthen international cooperation, including through a critical look at its current deficiencies. At times, grant recipients can feel like they are responding more to donor country agendas, internal funding timelines, and bureaucratic decision-making structures than to local needs. Media support suffers from a further handicap because it is so institutionally dispersed, coming from a variety of thematic and regional subunits, each of which imposes a different understanding and set of goals related to media.

These conditions have historically made it challenging to develop robust and coherent cross-donor approaches and provide nimble and strategic support for the long-term health of media ecosystems. Now more than ever, donor reform is needed to confront the complex cocktail of economic, political, and technological disruptions affecting media and threatening freedom of expression.

“It is a challenge for us to focus on our core missions to protect journalists at risk and promote independent media when most donors tie their media development funding to internal electoral priorities,” said Ayman Mhanna, the executive director of the Beirut-based Samir Kassir Foundation. “Donors have been prioritizing short-term projects that aim at countering violent extremism and addressing migration and disinformation at the expense of supporting long-term capacity building for independent, high-quality journalism—the sort of which contributes to building stable, secure, resilient, and well-informed societies.”

Perhaps surprisingly, donors overwhelmingly agree and would like to deliver a raft of changes demanded by grantees; they want to provide support that is “demand-driven, coordinated, contextually tailored, and oriented toward long-term, strategic goals.”1 Donors would also like to ramp up the amount of support provided to media development, recognizing that a failure to marshal a global response to the complex challenges in the media sector imperils the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).2

While such changes are a valuable first step, donor organizations face a variety of institutional challenges—thematic and departmental silos, limited human resources and expertise, and a lack of internal coordination—that can inhibit their abilities to translate such broad goals into sustained action for media support. In addition, the challenges facing independent media worldwide are so monumental, so complex, and so contextual that donors cannot possibly fix these problems alone. Mechanisms for collaboration across donors—including bilateral aid agencies, multilateral bodies, and private philanthropies—must be enhanced to better respond to emerging threats, coordinate national and international responses, and channel the demands of recipient governments, media outlets, and civil society organizations. Moreover, donors need help from one another to solve the shortcomings in media development assistance. They need more opportunities to learn from one another, they need partnerships that can encourage their institutions to change, and they need to delineate their respective roles within a more robust and concerted effort to promote development in the media sector. Additionally, the media development donor community can learn much from other multi-donor efforts such as the Open Government Partnership3 and the awkwardly named “UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity.”4

This report, based on 27 semi-structured interviews with representatives of donor organizations5—public and private, bilateral and multilateral—has dual aims:

- To better explain the organizational dynamics within donors organizations, shedding light on the nuts and bolts of the institutional frameworks and processes that structure internal decision-making, political will, and incentives around media aid

- To provide recommendations for how donors can overcome the institutional challenges that prevent them from coordinating with one another and from providing more effective, long-term assistance

The report begins by looking broadly at the structure of the media development landscape, the diverse range of actors involved, and the varied ways that media assistance is defined, explained, and justified across and within donor organizations. It outlines how the institutional architectures and internal incentives of these organizations inhibit their abilities both to respond strategically to today’s complex media issues and to understand the demand signals coming from individual countries and civil society actors. It then explains how donor organizations can overcome these institutional challenges by making ongoing commitments to 1) increase organizational capacity around media issues via internal learning, coordination, and advocacy; and 2) invest in the development of sustainable media ecosystems at the national and regional levels.

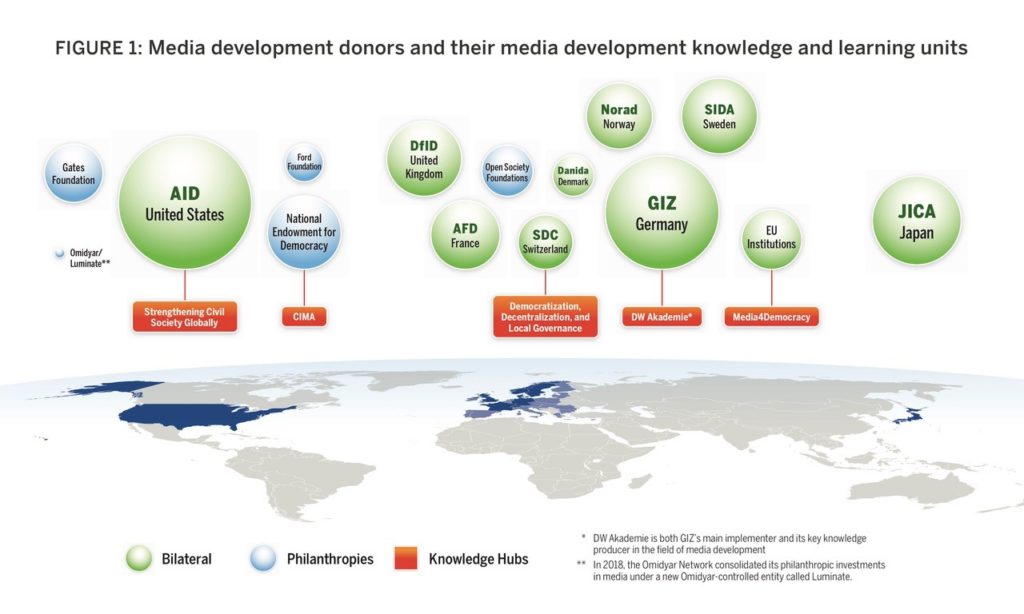

The Complex and Decentralized Nature of the Media Development Field

While support to the media initially began in the late 1950s and 1960s, the sector expanded significantly in the 1990s, as media assistance was largely undertaken within the context of democratization efforts in Africa and Eastern Europe.6Attention to the media sector grew substantially over the next decade, as international aid organizations increasingly prioritized the role of media as a subcomponent of the good governance agenda.7 In a paper prepared for the 2014 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Network on Governance (GovNet) meeting, participating donors acknowledged that “there is a renewed recognition that technical solutions are limited and an understanding of the political context matters. Media, and the enabling environment for its development, is recognized as a critical part of any system of accountability whether it relates to service delivery in a sector or resource mobilization such as budgeting, natural resource management or taxation.”

Many of the donor representatives interviewed for this report believe that commitment to the sector is growing. Official donors are recognizing media development as a priority, for instance, in the UN post-2015 SDGs, which included a target (16.10) focused on public access to information and protection of fundamental freedoms.

Despite this increased acknowledgement within official development agendas of media’s vital role in good governance, support to media development still scarcely accounts for more than 0.3 percent of official development assistance coming from governments and multilateral agencies, or about $450 million per year.8

Additionally, across this field of donors, the concept of “media support” itself has been difficult to define because it can refer to a wide range of activities that cut across many seemingly disparate governance agendas: from democracy promotion to economic development.9 Donor organizations and recipient governments also pursue media development with a multitude of aims. James Deane, director of policy and learning at BBC Media Action, parses the rationales that guide media-related aid agendas into four main categories: democratic and human rights objectives, accountability objectives, conflict and stability objectives, and communication for development objectives.10 Conversations and collaborations around the media, therefore, often take place in the context of one of the above categories, “prevent[ing] joined up strategic programming across government spheres.”11

Many of those interviewed for this research describe how the complexity of defining and rationalizing media support makes it difficult for media development to receive attention within the field as a distinct area. The diversity of strategic approaches and rationales for media support leads to the kind of aid fragmentation that development experts Stephan Klingebiel, Timo Mahn, and Mario Negre argue affects the “goals, modalities, and instruments” of how aid is delivered and the overall political economy of aid in this space.12

Institutional Impediments to Media Assistance

Many of these definitional and structural issues facing the media development field are replicated within the internal structures of development agencies and several of the large private foundations. Media development is frequently treated as a cross-cutting issue, as a strategic approach, or as a tool toward other governance ends. Seldom is it a distinct programmatic area within a donor institution.

As a result, media and freedom of expression can be deprioritized and understaffed. Media-related activities, strategic planning, and grantmaking are included within a diverse range of departments and programmatic areas focused on civil society, good governance, democracy promotion, accountability, and human rights. Only a few organizations, such as the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), explicitly reference “freedom of expression” as a core field of work within units working on democracy and human rights.13 Media programming is included within departments focused on conflict and post-conflict environments, innovation, and information programs, as well as within specific regional and country portfolios and departments. Alternatively, at both bilateral agencies and private philanthropies, media funding is often included as part of an instrumental, communication-for-development approach, in which media support is considered a tool for accomplishing other development aims such as public health.

The disjointed nature of media development within donor organizations means that the issue is supported in topical and regional silos, through separate budgets, across a range of expertises, and within a variety of measurement indicators. The varied ways in which media is understood across these organizational assemblages contributes to a lack of strategic coordination around how media support is allocated globally and regionally, who sets the agenda and makes spending decisions, which stakeholders are consulted, and which beneficiaries receive aid.

Andreas Reventlow from International Media Support commented on how the distribution of media activity across many diverse departments means it always “falls under a different strategy” and is rarely “media for media’s sake. . . . [Coherence around media activities is generally dependent on] how well-coordinated internally the local agencies are, and most are quite decentralized.”

Limited Human Capacity and Expertise on Media

The disjointed nature of media support within institutions also leads to limited expertise and human capacity to support media-related programs. None of those interviewed reported having more than four staff engaged on media issues in any department, and very few reported having even one specialist working on media issues full time.

In most cases, staff working in media support are part of small teams of generalists, responsible for a wide and diverse range of programming within their departments with limited time to devote specifically to media-related issues. Often, their knowledge and awareness of the media sector is learned on the job. Because these positions are subject to frequent turnover and staffing cuts, expertise in media development varies significantly over time, as do approaches to understanding and supporting the media as a sector. Several organizational representatives interviewed noted the real constraints that this limited capacity has placed on their departments.

Helena Bjuremalm from SIDA described how a lack of specialized staff limits the ability of donors to mobilize support for media throughout the organization. She explained that “very few donors these days . . . have a full-time media advisor that can be the ambassador within the agency or organization to push for [media-related] issues and strive for more coherence or innovation.” Andris Kesteris, the principal civil society and media advisor at the Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations at the European Commission, pointed out how a lack of media expertise limits the ability of his organization to use research and evaluation to understand the role of the media sector. He explained, “to be effective, you need to be precise. To be precise, you need to have expert advice . . . but we are civil servants, not experts.” Challenges like these related to human capacity and expertise exist at various organizational levels.

At the country office level, informants described similar issues related to human capacity and expertise. Because these offices are involved in budgeting as well as forging connections between local civil societies and media stakeholders, a lack of knowledge about media has significant implications for whether related issues are prioritized. Ambroise Pierre at the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) remarked on the lack of media sector expertise among country-level staff:

“Generally, a project is being proposed to our headquarters by the agencies on the ground at the local level. . . . When it comes to the media . . . the mandate is very recent for AFD. So it means that our agencies are not really used yet to identifying projects in that field yet. They don’t have people with experience in media support.”

Similarly, Corinne Huser from the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation described how country office staff “lack awareness of or fail to think more systemically [about media issues]” when setting priorities and allocating funding. Other respondents described how awareness of media issues at the country level is variable and usually based on experiences with specific programs.

Even when country-level staff do include media-related activities in their program budgets, the strategic aims of those activities vary according to the preferences of the country staff as well as perceived local needs. Will Taylor from DFID described how “in countries where they have a large program which is related to the media then, I think, a large proportion of some individual’s time will be media related, but there are often not specific media specialists that are operating there.” As such, country-level staff attempting to successfully carry out media-related projects may struggle to do so.

These findings echo a 2018 survey by the Global Forum for Media Development (GFMD) that found that of its members—media development organizations operating around the world—56 percent of respondents saw “low donor understanding of journalism support and media development” as one of the greatest challenges facing these organizations.14 The GFMD report cited similar capacity-related issues to those discussed above, including “frequent staff turnover, the rarity of specialized staff, and a lack of dedicated strategies” as factors that “complicate the prioritization of journalism support and media assistance.”15

Misalignments of Support and Needs

Many donor organizations acknowledge that previous approaches to media assistance have focused inordinately on trainings for journalists, content production, and short-term initiatives. This has come at the neglect of support for the larger media ecosystems—the technologies, producers, consumers, and social forces16—that are all part of the enabling environment for a free and independent media. Recent research by CIMA found that certain needs identified by media practitioners and advocates in regions around the world, such as support for media literacy programs, are largely unaligned with current donor support.17

This funding misalignment is also depicted by GFMD’s survey results in which 53 percent of all respondents described poor alignment between the sector’s needs and donor priorities as a major challenge in the field.

As mentioned previously, donors too are aware of the challenge. At the April 2019 OECD meeting of donor representatives, participants emphasized the need to create “agile and locally driven programs” to make media sector support more bottom-up and coordinated. Even with these good intentions, factors internal to aid organizations limit the ability of donors to understand and respond to demand signals from countries and civil society actors.

Informants described how the decision-making processes in donor organizations frequently preclude media-related factors from being considered while building aid programs. Indicators focused on media and freedom of expression issues, when they are included in the diagnostic tools and political economy analyses used in national agenda-setting processes, are relatively limited and do not provide rich data about media and freedom of expression issues or the health of national media ecosystems. Further, the results of these assessments are incorporated into programming only at the discretion of country office staff.

Will Taylor (DFID) explained how “DFID has a primarily country-led funding model where projects are designed and selected on the basis of local analysis. Those analytical processes have elements of media analysis within it. But some countries choose to focus on it. Some countries choose not to.” As a result, the responsiveness of donors to country-level demands fluctuates considerably depending on who staffs the office and how they conduct this local analysis.

CIMA’s report also outlines a goal set by donors to both “move away from donor-driven solutions and toward ownership at all levels of the process, which local practitioners enabled to experiment, learn, and lead the way toward more impactful solutions” and “foster opportunities for coordination at the country level.”18 However, donors themselves rarely have a relationship with local media stakeholders. Due to the low capacity and expertise of organizational staff, specialized knowledge about media issues is often held by outside consultants or intermediary organizations. These individuals and organizations often play a bridging role between the donor organization and local actors, developing an understanding of local needs, as well as building relationships and liaising with local media stakeholders within countries. The intermediary organizations are also highly professionalized and have the capacity to administer large multimillion dollar grants.

Respondents noted the important role these intermediary media organizations play within the field by providing aid organizations with expertise in the sector, local and trusted relationships on the ground, and professionalized program delivery. They are often actively engaged in advancing media development research and advocating for attention to these issues internationally and within their home governments. However, some respondents also noted that in some cases this intermediary structure may dampen the ability of local organizations to build professional capacity.

Indeed, the GFMD study of beneficiary organizations, discussed above, outlined how the dynamic between large international intermediary organizations and smaller regional and national organizations “can create the impression of a small inner circle (often characterized by preferences for large organizations of the same nationality as their donors), which further shrinks the ability of smaller, local organizations to directly access funding and build their own relationships with decision-makers.”19 Further, the GFMD survey revealed that beneficiary organizations “reported difficulties in covering a wide variety of organizational needs through donor support, particularly fundraising (52%), human resources (46%), and unplanned emergency needs (36%).”20 Ninety-four percent of respondents “expressed the desire for more institutional/core funding.”21

Case Study: The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation

Cross Departmental Thematic Unit on Democratization, Decentralization, and Local Governance

In 2008, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) launched its cross-departmental thematic unit Democratization, Decentralization, and Local Governance aimed at developing knowledge, exchange, and peer learning programs across the SDC on a variety of issues related to democratization and governance. Its three-person team of generalists produces knowledge, provides advisory services, and develops new programs in collaboration with external actors, distributing information via both field offices as well as SDC’s network of organizational stakeholders located in each of its geographic divisions. These activities aim to enhance and make more visible the peer expertise that exists within SDC and its wider thematic network of implementing partners and affiliates—such as experts within universities and media advocacy organizations—working on local governance, decentralization, and democratization around the world.

In 2016, the unit began to build greater understanding and coordination around media throughout the organization, commissioning both a study to better understand SDC’s media-related activities as well as a literature review on the state of international aid to media and donors’ approaches to media support. According to Corinne Huser from the unit, these efforts were meant to increase understanding not only of “what” SDC was doing around media, but also of “how” the organization actually operated in areas related to media assistance. Staff use their network and this research to build awareness, knowledge, and communication around media issues within other units and country offices. They also help those units and offices integrate media into programs, such as those focused on local governance and accountability, and create connections with media actors. The unit is also continuing to develop mechanisms to promote research, in-house expertise, and learning outcomes; sustain interest in the media; and ensure that awareness-raising and learning are continuous and operating at a variety of levels within the larger organization.

Will Private Media Development Donors Fracture or Unify the Field?

Support for media development has remained a small segment of international assistance, but that may be about to change. As donor support for the media sector grows, will it unify into a more coherent field of international cooperation, or splinter further? The answer to this question will depend significantly on the relationship between official and private donors, as private philanthropies engaged in development and human rights work increasingly acknowledge the vital role of the media, both institutionally and instrumentally, in supporting political, social, and economic development.

The foundations involved in the media development field do not fall neatly into one category or type, as individual foundations define media support through a variety of topical lenses, organizational justifications, and approaches. Some foundations—such as Open Society, Knight, and Ford—have been exploring and promoting the relationship between media and democratization for decades, while others are just beginning to incorporate media into their portfolios. Another large group of organizations in the space are guided by a theory of change that focuses on media production and content as an instrument for other human development goals. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is perhaps the most important example of a foundation currently supporting the media sector under this logic. A final subset of private philanthropic organizations is distinguished not by the organizations’ rationales for funding media, but rather for their approach: direct investment in media enterprises. The two organizations leading in the media investment space are the Media Development Investment Fund (MDIF) and Luminate (of the Omidyar Group).

According to figures collected online by the Foundation Center and Media Impact Funders, private philanthropic contributions to international media development are on the rise. Because of the imprecision of donor reporting, those contributions are best expressed as a range. In 2010, private philanthropic support to international media development was likely between $28 and $87 million. By 2016, that figure was probably between $86 and $136 million.22 On average, between 2010 and 2016, private funders contributed approximately $110 million every year to international media development.

Though private philanthropic actors have much smaller financial footprints compared with those of governmental donors, private donors in this space devote a larger portion of their budgets to media support. US private donors dedicate about 6 percent of their funding to supporting international media, compared with 0.3 percent of official development aid that goes to the media sector.23 In addition, these organizations play a variety of important roles within the field due to their relative political independence, capacities for innovation, smaller and more nimble operating structures, regional networking and convening capacities, and expertise and knowledge production activities.

Smaller, Nimble, Independent, and Responsive

As most of these organizations operate at a smaller scale and with less bureaucratic decision-making processes than their public counterparts, foundations are often able to act more nimbly and swiftly in response to emerging threats, priority issues, and new actors. Several respondents noted the dexterousness that comes from having a smaller budget and a less political and complex agenda-setting process. In addition, bilateral organizations often face political constraints with regard to media support in countries where the government is hostile to independent media. Private foundations, on the other hand, are less tethered to foreign policy objectives than their public counterparts and have more latitude to operate in opposition to repressive government policies. That said, private foundations and their beneficiaries face unique risks while operating in these environments, particularly when the foundations themselves are branded as partisan by illiberal regimes. A few of those interviewed noted the importance of addressing these challenges collectively as a way to minimize risk of exposure of individual funders and to work together to identify emerging threats.

Innovative Approaches, Financing, and Appetite for Risk

With this relative flexibility and independence, foundations have also contributed to the wider media development field by experimenting with financing modalities and by making numerous smaller investments that encourage innovation. Foundation representatives noted that they often have a unique ability to provide seed funding: smaller grants with longer time horizons suited to incubate projects and organizations. Several of the representatives interviewed for this research also described a gradual movement away from project-oriented funding and toward core support to organizations, especially for small independent media houses. Foundations have supported media accelerators such as the Open Society Foundations–funded JamLab in South Africa and New Ventures Lab for women journalists in Brazil, the MDIF-funded Media Factory news accelerator in Argentina, and the Omidyar/MDIF-funded South Africa Media Innovation Program.24 As suggested by the OECD-DAC, “given the right conditions, foundations can provide an incubator for new development ideas. They can also provide a testing ground that enables those ideas to be proven in practice before being more widely implemented through government programmes.”25

The Media Development Investment Fund, now a major actor in the media assistance space, was originally initiated through grants from the Open Society Foundations (formerly the Open Society Institute) as the Media Development Loan Fund in 1993. Since then, MDIF has been at the forefront of efforts to bring capital to the media sector and build management and revenue-raising capacity, especially within fragile or transitioning contexts. While investment-oriented philanthropy is still only a fraction of total media assistance,26 this could be an area for potential growth, including through partnerships with philanthropies, official donors, and private equity. Interviewees describe more of an “appetite for risk” to support media institutions in places where independent media are threatened as well as media ventures with innovative approaches to revenue generation. Government donors are increasingly interested in building partnerships with organizations with expertise in media investment to build new vehicles for media development aid. These alternative strategies and perspectives can provide means for new capital to enter the sector, new development actors to get engaged in the field, and for a variety of public and private actors to diversify their approaches to independent media assistance in contexts where traditional aid strategies have proven more difficult.

Specialized Expertise, Research Capacities, and Notions of Impact

As described above, staff working on media-related portfolios within government agencies are often generalists, largely operating within small departments with staff working on a variety of governance issues. In contrast, many of those interviewed from philanthropic organizations described staff as being recruited from within journalism or the human rights field and often having strong specialized academic backgrounds. These staff not only bring their knowledge of the media field and subject matter but also their trusted relationships with actors within local and international media communities to the organization.

In addition, many of those interviewed from philanthropies, especially from foundations such as Gates and Omidyar that emphasize technology, innovation, and R&D within their core values, described a particular advantage related to measuring and evaluating impact using new methodologies, tools, and technologies. These organizations have developed sophisticated ways to track the impact of media-related investments and understand the impact on the economic and political health of media ecosystems. Such methodologies could be used to support better diagnostics in coordinated, multi-donor efforts in media development.

Regional Expertise, Coordination, and Network Building

In addition to sectoral expertise, many foundations hire local staff across regional and national portfolios to ensure that foundation agendas are determined by contextualized expertise and local needs. Nishant Lalwani from Luminate described a process in which they “mainly invest in countries where we have people on the ground” and “rely on local expertise to maintain networks and conduct research.” Several of the largest foundations working on media issues, such as the Open Society Foundation (OSF) and Ford Foundation, operate out of regional or national offices (Ford with 10 regional offices and the OSF as a constellation of national offices and foundations in seven regions) with local leadership generally operating relatively autonomously.

These regional program officers are also aware of the activities of other donors in the region and often serve as conveners for regional dialogues and information sharing. As described by Paul Nwulu (Ford), “We try to find out what our peer foundations in the region are doing . . . and try not to replicate what has been done already.” Most of those interviewed described this regional dialogue as existing largely between private philanthropies, with engagement between public and private donors occurring far less frequently.

However, in a similar pattern as with the largely decentralized government agencies, the federalized structure of these larger foundations can also result in regional discrepancies in the attention given to media issues, depending on the region, country, and staff backgrounds. These kinds of discrepancies can lead to uneven growth with regard to issue and expert networks in particular regions. Several interviewees described highly interconnected and collaborative foundation networks in Latin America and Europe, but less so in Africa, Asia, and especially the Middle East.

Building Institutional Support for Media

The above section outlined many of the institutional challenges facing donor organizations as they attempt to adapt their practices to the complex, structural issues facing independent media around the world. While the cross-cutting nature of media aid does present challenges related to coordination, it also can provide opportunities for “mutual learning and innovation” across and within organizations and building support for and knowledge about the media among diverse stakeholder groups.27

The subsequent sections provide insights, illustrated by examples, into how organizations can mitigate these internal challenges by increasing organizational capacity around media issues via internal learning, coordination, and advocacy, and incentivizing a demand-driven systems approach to sustainable media development at the national and regional levels.

Internal Learning, Coordination, and Advocacy

This report has described how the cross-cutting nature of media assistance across uncoordinated organizational silos can create obstacles to greater and more strategic media assistance by limiting the availability of human resources and expertise specific to media development. Despite these common concerns, interviews with representatives of donor organizations revealed ways in which organizations can mitigate these issues by crafting creative mechanisms for developing internal expertise around expression issues, creating networks of media-assistance champions across the organization, and engaging knowledgeable allies in a variety of departments and country offices.

Cross-unit capacity-building and knowledge-sharing initiatives

One model that has been successful within organizations with constrained capacity and expertise has been the creation of thematic units that can build a media agenda across departments through knowledge sharing and capacity building. These units are frequently tasked to build internal knowledge, sustain and grow networks, and share expertise around the importance of media assistance. These advocates push for strategies that focus on the media, commission research, and develop coordinating mechanisms to connect decentralized actors across the organization.

Examples of successful cross-organizational coordinating efforts that have prioritized media include the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation’s cross-departmental thematic unit on democratization, decentralization, and local governance (which is described in greater detail earlier in this report); the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) Strengthening Civil Society Globally (SCS Global) Program; and the European Union’s (EU’s) Media4Democracy program.

Donors named a number of benefits seen from such initiatives. These efforts have been successful in improving networking and learning around freedom of expression issues, integrating existing media-related guidelines or mandates across the institution, fostering understanding of the connections between the media and other sustainable development goals, and connecting these nodes across departments and field offices. These units are able to better connect with media experts outside the organization and engage in global dialogues around media issues. These units have also created opportunities to recruit experts in media assistance. Over time, these activities build internal champions who can support aid to the media sector at a variety of levels.

Programs like these can also increase knowledge and coordination within regional and country offices. Many of these programs, such as USAID’s SCS Global Program, provide awards for media-related interventions and technical assistance for country missions and operating units. Implementation at the field level requires the extra step of making media issues relevant to the current on-the-ground realities of country-level staff and local partners. The EU’s Media4Democracy program provides country delegations with resources and expert guidance on how to include media and freedom of expression issues in EU Democracy Action Plans, in Human Rights and Democracy Country Strategies, and as part of EU democracy support.28 Adel Anna Sasvari, a program manager in the Gender Equality, Human Rights, and Democratic Governance unit at the European Commission, described how the Media4Democracy program was created in response to the lack of both “systematic tools for each delegation on how they do freedom of expression and media landscape assessments” and human capacity and expertise around media issues.

Strategically engaging leadership on media-related issues

Developing and sustaining new intra-organizational programs around media requires buy-in from institutional actors at a variety of levels, most importantly from organizational leaders with power over agenda setting and budgeting. Yet sustaining attention from leadership represents a serious challenge. Interviewees within these organizations noted the importance of having external actors, such as international advocacy organizations, research institutions, and knowledge-sharing networks, push for continued attention at these high levels through lobbying.

Efforts should also be made to include those at higher institutional levels within coordinating bodies and information-sharing activities in a sustained way, providing resources to continue to make clear the relationship between the media and other development aims as well as the sector’s vital role in democratic functioning. GFMD’s study of member perceptions suggests that SDG 16:10 can be used as a vehicle to “demonstrate that media and information are not just rights in and unto themselves, but they can also be enabling rights for other SDGs—such as gender equality and those related to the environment—and thus important and relevant for the whole SDG agenda.”29 Indeed, a few respondents noted that the adoption of SDG 16:10 encouraged organizational leadership to engage more explicitly within debates around media and governance and, in some cases, to prioritize media within programming, particularly in those organizations with existing or developing internal guidelines focused on media and freedom of expression. The broad aims outlined in 16:10 can thus be made actionable and relevant across departments through specific organization-wide objectives, best practices, and indicators to track outcomes and impacts.

Tailoring media for diverse needs and demands

While the decentralization of media assistance activity within donor organizations presents numerous challenges, the blurring of approaches and rationales for media support also offers opportunities for outreach to and collaboration among diverse internal departments across governance, human rights, and development spaces. Caroline Giraud (Media4Democracy) explained how they work to “give some concrete ideas and examples and best practices on how freedom of expression or access to information can be embedded into other types of sectors and priorities,” such as climate change and economic development. Many interviewees also acknowledged that more actors within the development community are recognizing the importance of a stable and trusted media sector as a prerequisite for functional democratic governance. Media support advocates have been able to capitalize on increased demand from tangential departments and units to build opportunities for knowledge building, networking, and increased political attention. According to Kristin Olson (SIDA), such scenarios—in which organizational actors not working on media raise the need for media expertise—generate increased credibility for media programs within organizations.

As with organizational leadership, there is also the potential to leverage the SDGs to connect actors across departments and thematic organizational silos. However, while the SDGs and other high-level strategic priorities and organizational guidelines provide a vision for leadership and goal setting at the international level or at headquarters, there is a need to figure out how to operationalize these broader goals and make them locally applicable. Informants stressed the importance of translating top-level guides and mandates into tools and resources that are usable by staff working at the country level and relevant to their day-to-day operational challenges. Caroline Giraud (Media4Democracy) described how they seek to engage delegations with less knowledge about media and journalism by creating social media kits and practical guides to raise awareness about access to information issues or to support the safety of journalists. Similarly, Paul Nwulu (Ford Foundation) explained that while Ford’s mission and program objectives related to the media have changed over time, he has still been able to interpret these objectives in ways that fit for the specific regional needs of the West African office.

A Media Ecosystems Approach to Agenda Setting: Recognizing and Responding to Demand Signals at Regional and National Levels

While increased internal coordination around media issues has the potential to create efficiencies, increase awareness, and improve communication across donor organizations, providing demand-driven support aimed at sustainable structural change will require an approach that involves comprehensively understanding and strategically supporting the unique media systems that exist in specific geographies. Key informants from across bilateral, multilateral, and intermediary organizations and private foundations expressed renewed interest in thinking about media support in this holistic and sustainable way. Actions that were identified that can be taken toward those ends include the following:

- Improving diagnostic tools and establishing processes of co-creation in country-level agenda setting

- Building relationships and developing local multi-stakeholder networks

- Incentivizing coordination at the regional and country levels

- Crafting innovative and responsive approaches to media support

Improved diagnostic tools and processes of co-creation in country-level agenda setting

As discussed above, the country-level agenda-setting processes through which aid organizations evaluate individual countries and regions reveals very little about freedom of expression issues or the health of national media ecosystems, with significant implications for how media is included in strategic priorities and program budgets. Informants described ideal systems in which donors holistically analyze the media landscape and anticipate potential areas of need. Kristin Olson (SIDA) described a process through which donors would anticipate potential areas of need by thinking through a wide variety of questions similar to those considered for other areas of governance and development. According to Keiichi Hashimoto, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), as part of its work supporting public service broadcasters, sends a team to countries for several weeks to engage in comprehensive research aimed at understanding “the landscape as a whole . . . and more deeply into the target organization.” JICA also evaluates the local audiences that exist in individual media systems, particularly around media literacy and trust in media institutions.

Some donors are working toward a process of co-creation, in which consultation with local actors and organizations ensures that programming is contextually relevant and demand driven. For example, USAID’s recently published Acquisition and Assistance Strategy notes a shift toward engaging with “partners and beneficiaries much earlier in the planning process as co-designers, co-implementers, and co-owners of their own development objectives.”30 The report goes on to note that “missions will apply country context in their plans and strengthen and measure the capacity of local actors to achieve and sustain inclusive results. This will include providing platforms and services that make it easier for Missions to harness open innovation and partnering approaches.”

In addition to their own field assessments, representatives from USAID noted that they support IREX’s Media Sustainability Index, “which uses focus groups of key stakeholders in media communities that assess the state of local media and highlights gaps in the sector that can be addressed by donor activity.” These kinds of approaches and tools can be enhanced within organizations and shared across donors to pool knowledge and more strategically and efficiently understand the needs, opportunities, and challenges of specific media ecosystems. However, for holistic assessments and consultative agenda-setting processes to truly reflect country-level demands, they must draw on a wide range of local stakeholders.

Building relationships and developing local multi-stakeholder networks

For this and other reasons, donor organizations describe the need to build and sustain networks of local stakeholders and expand these networks to include new actors that have previously been less engaged in media development activities. Improved national- and regional-level engagement and network building can help develop local capacities for responding to new threats to media freedom and democracy, provide linkages and communication channels between practitioners and policymakers, and enable national stakeholders to connect to regional and international advocacy organizations and networks.

Several informants from bilateral and implementing intermediary organizations stressed the need to use an approach to preparing for and engaging in network building that prioritizes long-term, mutual relationships of trust, listening, learning, and open communication. They noted the importance of first having a clear understanding of the civil society and media sector organizations working in a particular country or region, and ensuring that those working in the field (within country offices or through implementing partners) both hire local staff knowledgeable about the media sector and speak to a variety of people engaged in related activities. Andreas Reventlow from International Media Support described the importance of “tap[ping] into . . . networks of knowledge through a local employee who speaks the language and who understands the culture and the context,” taking care not to adversely impact “whatever nascent structure is already there if you’re not doing it in a way that creates some legitimacy for yourself.” Several donors also reiterated the importance of coordination and communication between the media specialists at headquarters, who can provide media-related expertise and resources, and those in the field with expertise on the specifics of the country’s political realities and the ability to connect with local groups.

In addition, donor organizations are thinking through how they can provide increased institutional support and involve a larger range of actors to promote the long-term, structural change necessary for a vibrant and sustainable media sector. Informants frequently mentioned a need to think about these network-building activities as a means of maximizing local capacities by engaging with both traditional media development partners as well as with new stakeholders within the larger media ecosystem. As described by Helena Bjuremalm from SIDA, “the standard formula for support to media is to train individual journalists. At the same time, most journalists and donors are very tired of that model because there’s little sustainability and little mobilization, and there’s basically no structural change. It’s like approaching the health sector by training individual nurses, only.” Kristin Olson (SIDA) noted that there is also a need to move beyond capacity building for journalists to include training for specialized skills and knowledge that have been largely underemphasized but are vital in protecting and supporting independent media, saying “what we don’t have today, for example, are civil society actors that are specialized in different financing models for journalism, specializing in legal issues and media law, specializing in tax law for media registration issues, licensing, auctioning at the national level.”

Network builders should seek active participation not only from journalists and civil society actors, but from those in the private sector, judiciary, technology sector, youth groups, academia, and organizations focused on related human rights and development issues. According to Kristin Olson from SIDA, there is a need to expand support to activate passive supporters and media stakeholders, saying “we need mobilized media owners, media actors, media lawyers, politicians, and democracy researchers to proactively create a vision of a media reform in countries where there are no reforms made.” Representatives from USAID noted that there should be increased efforts to “focus on budding, young entrepreneurs rather than reverting to the usual players.” Peter Bøgh Jensen from the Department for Humanitarian Action, Migration and Civil Society at the Danish International Development Agency pointed out the need to also reach beyond urban centers to engage with actors and organizations in rural areas.

With large networks of diverse stakeholders, there will be the potential for developing robust multi-stakeholder local coalitions that can push governments for improved programmatic and policy outcomes. Such diverse coalitions can better think through and handle both political and economic threats to independent and plural media systems due to the diversity of approaches and opportunities to engage with decision-makers throughout media and political systems. Informants from bilateral organizations also noted that they are uniquely placed to help civil society organizations and journalists build linkages with government officials and policymakers.

Building incentives for coordination at the regional and country levels

Informants suggested that communication and harmonization of donor diagnostics, objectives, and activities could lead to efficiencies in, and increased impact of, media assistance across individual regions and the sector as a whole. Current local engagement strategies for media support are frequently driven by the activities of intermediary implementing organizations operating in a specific country or region. Representatives from both intermediary and bilateral organizations discussed how these organizations’ local networks and specializations have at times allowed these organizations to serve as de facto nodes for the sector, coordinating activities across donors, civil society groups, lawyers, policymakers, and journalists within countries or regions.

While this type of coordination has emerged at both the national and regional levels in certain circumstances, with the exception of ad hoc organization or coordination around critical events (such as elections or crises), neither meaningful participation by donor organizations nor efforts to sustain national networks regularly occurs. Though the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness did highlight the need for harmonization of aid programming and donor processes, subsequent discussions on the subject have focused only on streamlining donor processes and coordinating donor activity at the international level. However, many of those interviewed described a need for more effective donor coordination at the national level, as well as better attempts to specifically mobilize media support efforts within individual countries.

Several informants offered potential solutions to develop more coherent and strategic program coordination between donors in the field. Pierre Ambroise (AFD) described how regional coordinating initiatives can offer opportunities for donors to better and more strategically collaborate and understand specific regional issues. Considering the role that private foundations play as coordinating bodies in specific regions, efforts can and should be made to bring together private and public donor capacities to convene, share knowledge, and set multi-donor agendas at the regional level.

Further efforts to improve donor coordination around media development could follow the strategies outlined by economists Wolfgang Fengler and Homi Kharas for improving national-level aid coordination, including the designation of a government agency or working group to oversee the coordination process, the design of transparent information and data systems that allow donors to clearly identify what work is already being done by other actors, and assignment of certain donors to key sectors they are particularly active in as a means of improving aid effectiveness.31 Caroline Vuillemin from Fondation Hirondelle also noted that donors could more explicitly incentivize coordination by specifically providing funding opportunities for actors to serve as these coordinating bodies at the national or regional level.

Crafting innovative and responsive approaches to media support

In addition to building mechanisms for coordination and co-collaboration at the national and regional levels, there are opportunities for donors to think through innovative forms of media support beyond traditional approaches. While most media assistance is distributed via large grants through bilateral and multilateral institutions, many donors are exploring new funding tactics and partnerships that could expand revenue sources for media, offer the potential for more strategic funding, and incentivize localized strategies and experimentation.

- Beyond grants: Investment vehicles and partnerships

Beyond programmatic coordination, there are other ways in which donors can partner to address the financial challenges of media outlets and the sustainability of their business models. Interviewees from aid organizations mentioned emerging modes of support beyond traditional grantmaking, including partnerships to support media through impact investment and directed activity associated with development banks. Several respondents mentioned SIDA’s partnership with the Media Development Investment Fund. While SIDA had long partnered with MDIF on a grant basis, in 2016 SIDA engaged MDIF to create a blended-value loan fund to provide loan guarantees to fund small and medium-sized independent media enterprises in emerging markets with riskier political contexts. These loan guarantees incentivize other investors by mitigating risk and could potentially build support for increased private investment in media in countries where the press is most threatened. Other donors, such as the Swiss Development Cooperation, have engaged in these kinds of public-private partnerships and loan guarantees for independent media development, and have served as models for other donors seeking to engage more with private actors to mobilize support for the media across a range of approaches and with the buy-in of a variety of stakeholders. Andris Kesteris from the European Commission described how these organizations are helping to get larger, more bureaucratic public institutions to try to think about how to support the media from the “point of view of a sector of industry” and not exclusively from a human rights perspective, increasing the potential for investments in small and medium-sized enterprises in the media sector. Kesteris (European Commission) and Nishant Lilwani (Luminate) both noted the importance of considering new strategies such as investment as one part of a diversified, holistic approach to media support.

- Leveraging competitive advantages across funders

Many respondents described how the levels of funding provided by bilateral and multilateral governmental organizations are often too large to support individual outlets or strategic activities during specific moments of crisis or instability. Mira Milosevic (GFMD) described how GFMD’s research indicates that most government donors “don’t have the capacity to give a lot of smaller grants,” making funding less “accessible to local outlets” and making it harder for them to address issues of local media sustainability in a systemic way. Private foundations, on the other hand, can move more swiftly and nimbly to provide smaller grants and mobilize rapid response programming. Foundation representatives noted their ability to provide smaller seed funding grants given over longer time horizons to incubate projects and organizations. As described by Harlan Mandel (MDIF), “it’s been effective to . . . concentrate resources of funding and training and advising with a small number of high potential actors over a long period of time.”

Alberto Cerda Silva (Ford) described how Ford’s regional office program officers have engaged in more “contextual” and “intersectional” grantmaking related to the media and technology. Better coordination between these large private grantmaking organizations and other large, small, private, and public donors could encourage increased innovation across the field as private donors can make small investments in more risky or inventive programs. As previous research by OECD-DAC has suggested, such programs provide a testing ground that enables those ideas to be proven in practice before being more widely implemented through government programs.

- Collaborative funding mechanisms

Considering the fragmented nature of media support across and within aid organizations, donors also have a shared interest in leveraging resources and establishing shared objectives collectively. Several informants noted the possibility of building a collaborative fund for donors to pool resources. Some respondents noted that a global fund could solve the current problems related to decentralized expertise and agenda setting for the field. The GFMD’s report on beneficiary organizations revealed that “proponents of a global fund or similar model believe that such an approach could help reduce donor administrative costs, streamline proposal and reporting processes, shield funding from the political considerations of individual donors, and secure a steady stream of support.” The report goes on to cautiously note that other interviewees, “however, express concerns that a centralized process would face difficulty in accommodating different agendas and strategies, pose barriers in access and transparency, and undermine the importance of building relationships and trust.” While this level of synchronization at the international level might pose challenges with the wide range of organizations involved, piloting this kind of joint program at a national or regional level could offer valuable learning outcomes and the opportunity to later replicate the program in other contexts. Multi-donor funds have been considered successful by donors and experts alike in the past and provide an opportunity to coordinate funds more successfully and involve funding from small and large donors alike. The Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund, for example, was established by the World Bank and allows other donors to channel their aid through it.

Implications for International Cooperation on Media Development

At present, the structures of international cooperation are not prepared to meet the complex and urgent challenges facing independent media. With the international community gradually recognizing the gravity of the crisis and its impact on development and stability, that may change. Yet, as this report has highlighted, even with greater political will, donor organizations will need to resolve a number of institutional challenges—thematic and departmental silos, limited human resources and expertise, and a lack of internal coordination—to provide effective support for the development of healthy media ecosystems.

This report has described some of the reforms individual donor organizations can implement to prioritize, streamline, and operationalize media support goals within institutions. They include providing increased resources to enhance human capacity and expertise related to media issues within departments and field offices, building cross-department institutional structures tasked to coordinate and generate demand for media-oriented work, and offering opportunities for actors across the organization to become more knowledgeable media “champions” to advocate for increased attention to media issues within the agenda-setting process.

Obstacles to effective support in this field, however, also need to be addressed in the broader architecture of international cooperation. Media development assistance will require greater coordination among donors and key implementers and better mechanisms for generating demand for media support, including from recipient country governments. Addressing these broader weaknesses will require involving organizational stakeholders who have not been fully engaged on the topic of media development. In other words, donor organizations cannot fix the weaknesses in media sector support without working together and with others.

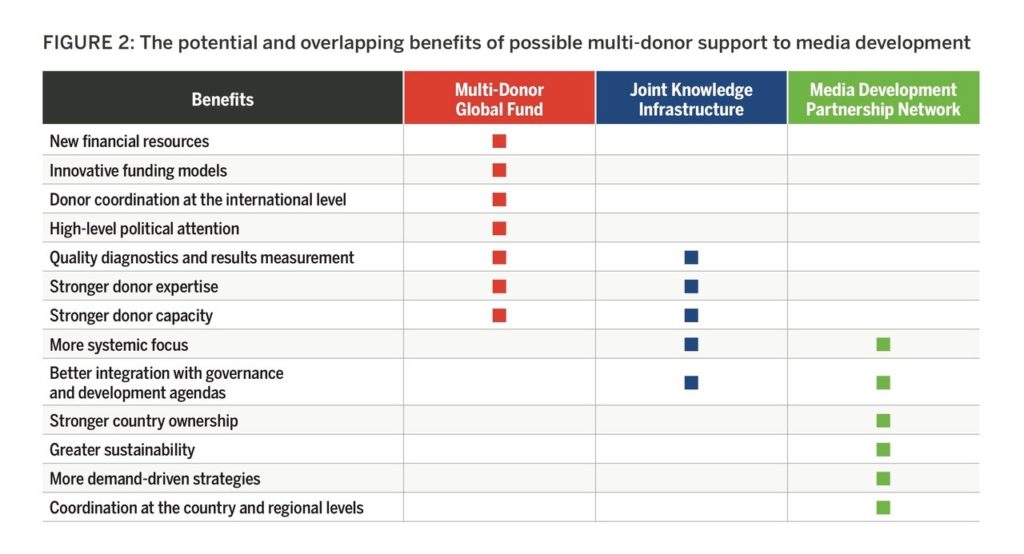

Fortunately, donors have begun to map out forms of collaboration with the potential to transform media sector support. Three types of collaborative initiatives were highlighted at the discussion in Paris and in subsequent conversations:

- A multi-donor global fund

- A joint knowledge infrastructure

- A media development partnership network

The findings from this report suggest that these collaborative efforts could solve many of the problems in media development assistance, but that none of these initiatives alone is likely to solve all of the challenges. In the case of the global fund, it could exacerbate existing problems under some conditions. These concluding points should be considered as donors discuss these three initiatives.

A global fund would help address five key challenges—but may exacerbate two problems.

Luminate has funded a feasibility study for the creation of a multi-donor fund with the mission of supporting independent public interest media in fragile and resource-poor settings. Other donors have expressed general interest in the idea, though the precise objectives, modalities, and governance of such a fund remain to be determined. Those contemplating creating a new fund have looked at the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the Global Innovation Fund, among others, as models for its institutional design. Evaluations and research of multi-donor funds have demonstrated the strengths and weaknesses of global multi-donor funds.32 Findings from this report illustrate how these strengths and weaknesses are likely to affect media development assistance in seven ways: five largely positive, and two potentially negative.

1. Additional resources: Global multi-donor trust funds have not succeeded in garnering additional resources when funds have been diverted from existing streams, but have been able to draw new resources to underfunded subsectors.33 Given the absence of a clear “media development” stream of funding at most donors, a global fund seems likely to attract new resources, which the current proposal indicates should be an essential condition for its creation.

2. Donor coordination: Multi-donor funds have succeeded in improving donor coordination at the global level, but have had mixed or poor results fostering coordination at the country level (more on this below). In the field of media development, global coordination leading to more coherent approaches and strategies would be a big step forward.

3. Improved expertise: This report has highlighted a lack of expertise on the media sector within donor organizations. Past experiences suggest that a global fund would likely help foster such expertise, including within the donor institutions contributing to the fund.

4. Innovation in funding models: Multi-donor funds have a strong track record fostering innovative funding modalities, including through partnerships with the private sector. Any eventual global fund for the media sector should look to maximize this benefit.

5. Quality diagnostics and results measurement: Global funds have also been associated with high-quality diagnostics and rigorous approaches to measuring results and impacts. In a field where independent evidence of impact has been lacking, a global fund could make a major contribution.

While a global fund could make positive contributions in the above five areas, two demonstrated weaknesses of global funds should be of major concern to those contemplating such an instrument for media development assistance.

1. Donor-driven with weak recipient ownership: Multi-donor funds have been criticized for exacerbating donor-driven approaches and weakening ownership by the people the funds are trying to help. International media development already suffers from this weakness. A donor fund that aggravates the problem would likely mire the fund in considerable controversy and undermine the effectiveness of assistance in the sector.

2. A narrow focus when broader systemic change is needed: Another major weakness of global funds has been an emphasis on narrow goals rather than on broader changes in the media ecosystem. In the literature, this is referred to as “verticality”: a laser-like emphasis on one aspect of development from top to bottom. Critics of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, for instance, have charged that it has focused too heavily on particular diseases at the expense of giving needed attention to health systems (indeed, this was one of the issues that undermined country ownership).34 Given what we know about the importance of the enabling environment for independent media, a narrow, or “vertical,” approach to media development would not likely succeed—at least not in the absence of a countervailing approach that emphasizes the media ecosystem.

Knowledge building should promote capacity development for donors and for partners.

A number of overlapping proposals have been put forward for shared knowledge services. Proposals have included creating an independent body that can assess the impact and effectiveness of different approaches, a help desk that can consolidate and share existing knowledge and lessons, and joint investments in research and diagnostics, such as the DFID-supported Protecting Independent Media for Effective Development project.35

The findings from this report suggest that knowledge-building initiatives would be beneficial to the sector. Such initiatives, however, need to be approached as a capacity-development endeavor, both for donors and for implementing partners, including many partners whose knowledge needs are neglected, such as government reformers, media councils, and regional bodies. Two components of joint knowledge-building efforts will be essential for strengthening assistance in the media sector:

1. Integration with thematic media units: Any jointly supported knowledge-building initiative should connect to the cross-organizational learning units described in this report, such as the EU’s Media4Democracy program. Any donor organizations planning to contribute to a global fund should be expected to create such a thematic unit. This would ensure that the donors remain capable of building broader complimentary agendas to the work of the fund, promote a more sustainable agenda, and can continue to meaningfully supervise the work of the fund.

2. Involvement of southern actors: Knowledge building that focuses exclusively on donor knowledge will do little to address the supply-driven nature of media development assistance. It should be designed to address the knowledge needs of southern actors and—just as importantly—to bolster the ability of southern actors themselves to produce forms of evidence and knowledge that can shape national strategies and the global effort to promote media development. This suggests that research and knowledge creation should be embedded in some kind of media development partnership network or within a joint effort to support coalition building.

A media development partnership network would solve several problems, but face limitations.

Donors have also expressed openness to the possibility of jointly investing in networks and coalitions that can support media development. An increase in collaborative support for media development coalitions and networks will also be an important way of addressing the shortcomings in the media development sector identified in this report. Cross-border coalitions and regional groups—particularly when working in conjunction with states and regional mechanisms—can integrate media into broader governance agendas, build political will, strengthen capacity, and exert influence in countries with less conducive environments for media development.

In particular, support for coalition building at the national, regional, and global levels could provide an important corrective on the supply-driven nature of assistance in the sector. It could also help build and sustain demand for more systematic approaches to media development, building the vital ownership that is needed in the sector. If a multi-donor fund risks skewing the sector toward top-down vertical approaches to media development, investments in coalition building would provide a counterbalance. Still, the issues highlighted in this report suggest that investments in media development partnerships would maximize their impact if accompanied by two other efforts from the donor community:

1. A more coherently organized donor community: Multi-stakeholder, cross-country networks and coalitions can translate national and regional media practitioner priorities for the donor community, but will donors be able to respond? Without donors formulating a more coordinated agenda-setting process at the regional and national levels, the demands expressed by the coalitions may not have a donor counterpart with the ability to respond. The creation of a global fund, or modalities for joint funding of coalitions, would likely incentivize joint agenda-setting processes.

2. Greater international pressure on governments: Coalitions and networks can take advantage of opportunities, such as the coming to power of reform-minded governments, and help create opportunities by cultivating allies within governments and regional blocs. But experience shows that such coalitions need the international community to champion norms and standards for media freedom and to hold governments to account and provide backing for reform agendas. Absent a strategy by the international community to back coalitions in these ways, coalitions are likely to see many of their victories stalled or reversed.36

This report has sought to describe the institutional landscape of the international media support community and the diverse range of goals and incentives that structure the possibilities for better coordinated, strategic, and demand-driven aid. The findings are intended to benefit donor organizations that recognize the vital role the media plays in promoting governance outcomes and the complex systemic challenges currently facing free and independent media worldwide. Through this report, we argue that the donor community must be ready not only to confront these challenges, but also to critically examine current approaches to media development and provide institutional infrastructures and resources to incentivize more strategic coordination and agenda-setting within and across donor organizations.

This report should give hope to those working on the frontlines of the battle to protect independent media—a wide variety of donors and important media development stakeholders emphatically support increased attention to the media sector and recognize that changes need to occur to make aid work better. However, recognition is only the first step. What must come next is a serious and collaborative effort to build new structures, processes, and information-sharing practices.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to the donor representatives and individuals who generously offered their time and perspectives for this report. Additionally, many thanks to Nick Benequista, Paul Rothman, and Mark Nelson at CIMA who provided valuable guidance, feedback, and editorial assistance throughout this process. CIMA intern Tyler Mestan meticulously compiled statistics on private foundation support for media development for this report.

Footnotes

- Nicholas Benequista, Confronting the Crisis in Independent Media: A Role for International Assistance, (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2019).

- Bill Orme, Strengthening the United Nations’ Role in Media Development (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2019).

- Paul Rothman, Media Development and the Open Government Partnership: Can Improved Policy Dialogue Spur Reforms? (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2019).

- Orme, Strengthening the United Nations’ Role in Media Development.

-

The methods used to compile the data used in this report are primarily derived from phone interviews with donor representatives from a selection of major national bilateral development aid agencies, private foundations with media-related grantmaking, and several multilateral organizations. These organizations were initially selected from a list of the top media support donors, derived from CIMA’s research on media assistance from 2010 to 2015. Additional interviews were added via snowball sampling recruitment. Due to organizational preferences and approval processes, one organization responded to interview questions in written format. Several interviews included more than one organizational representative to provide multiple perspectives from across institutional departments and agencies. These interviews sought to solicit insight about how these organizations conceptualize and operationalize media assistance, how media is institutionally situated, practices and processes that structure agenda-setting around aid to the media, challenges these donor organizations face with regard to media support, and the opportunities that exist for expanding attention and coordination within the field. Additional interviews were conducted with individuals at intermediary implementing organizations engaged in media development as well as experts working for organizations meant to coordinate the wider media development field. These interviews were conducted due to the instrumental role that these organizations play in determining agendas for media assistance, in coordinating with media stakeholders within countries, and in collaborating with donors and others in the field. Additionally, due to the close relationships between certain media development implementing organizations and their corresponding national donors, insights from these organizations were included to further illustrate processes and procedures within these funding agencies.In total, 27 one-hour interviews were conducted with 32 organizational representatives from 19 donor organizations (9 private organizations, 8 bilateral donors, and 2 multilateral bodies) and four media development ‘intermediary’ institutions. These interviews were each transcribed and subsequently coded within software used to collect and analyze qualitative data. Through this process, patterns and trends were identified across the interviews. Additional information was obtained from a supplemental survey distributed to interviewed donor representatives. This survey provided interviewees with the opportunity to provide links and additional information on official guidelines and strategic documents, research produced, and specific information on departmental approaches and policies. From this information, documents were reviewed, analyzed, and integrated into the findings. Additional desk research was conducted to supplement this review and to complement and contextualize insights from primary research with findings and analysis from previous research reports produced on media assistance and donor approaches within the field. This review of literature is integrated throughout this report to better synthesize findings, view trends across sources, and aggregate conclusions.

- Amelia Arsenault and Shawn Powers, “The Media Map Project: Review of Literature,” (Internews and the World Bank Institute, 2010).

- Mary Myers, Nicola Harford, and Katie Bartholomew, Media Assistance: Review of the Recent Literature and Other Donors’ Approaches, (iMedia Associates, 2017).