Key Findings

Social media platforms are having profound impacts on the practice of journalism, which now involves a complex interplay of technologies, journalistic routines, and media economies. Platforms like Twitter are particularly important for news outlets in developing countries and emerging democracies. Easy access to a wide array of sources enables newsrooms with shoestring budgets and limited human resources to produce journalism that includes the perspectives of experts and citizens who are often excluded from news stories. Despite this potential, the use of Twitter for newsgathering may be replicating the same “echo chambers” that have always existed.

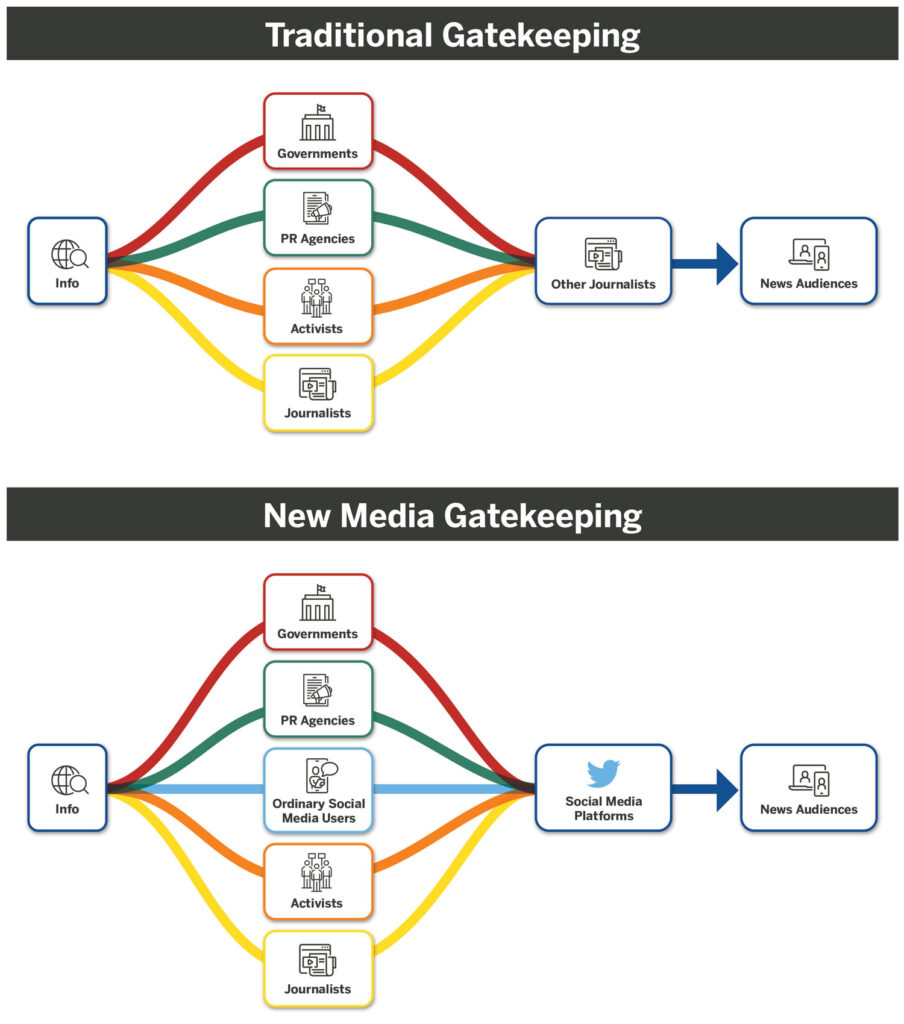

– The use of platforms like Twitter for newsgathering is disrupting traditional gatekeeping processes in news production. Journalists now have access to a wide variety of non-elite sources, story ideas, and content from sources beyond governments, PR firms, and other news organizations.

– Despite the potential of social media platforms, journalistic routines, norms, and practices may limit their ability to radically alter everyday news production. Journalists tend to follow the same sources they have traditionally relied on, and relevance-ranking algorithms direct journalists to content from media colleagues, politicians, and large institutions that have long served as information gatekeepers

– Local and international media support organizations need to work with media outlets in developing countries to determine how best to integrate new technologies into their journalistic routines and standard operating procedures while also helping them mitigate the risk of spreading user generated mis- and disinformation.

Introduction

Twitter holds the potential to enable journalists to diversify their reporting. Worldwide, and especially in developing countries, media outlets face several barriers to expanding coverage to include a diversity of events and perspectives. These include a concentration of media outlets in urban centers, shoestring budgets, and established routines for reporting that rely on elite gatekeepers. Twitter, in theory, may help provide the means to circumvent these barriers if journalists use the platform to generate story ideas, identify sources, and conduct research in ways that seek out new, non-elite voices.

Twitter has itself touted its usefulness to journalists. In 2015, on the social media platform’s ninth anniversary, founder and Chief Executive Officer Jack Dorsey gave special thanks to journalists and argued that they have a symbiotic relationship with Twitter in a series of tweets:

4/After the tech early-adopters, journalists were next to take to Twitter. They used it as a source, to break news, and to link their work.

— jack (@jack) March 21, 2015

5/Journalists were a big part of why we grew so quickly and still a big reason why people use Twitter: news. It's a natural fit.

— jack (@jack) March 21, 2015

7/Journalists make Twitter better by providing context, research, and a balanced perspective drawn from what the people experience.

— jack (@jack) March 21, 2015

Six years later, journalists around the world use Twitter daily for newsgathering.1 Yet the question remains whether journalists truly use the platform to expand the diversity of people and perspectives they cover in their reporting or whether they rely on a small, skewed subset of the population. There are several factors that may be reinforcing, rather than breaking, news echo chambers and journalists’ dependency on elite gatekeepers.

First, institutional routines, norms, and practices may limit the potential for platforms like Twitter to radically alter everyday news production. Journalists may “normalize” Twitter by simply using it as a faster and more efficient tool to access the same kinds of sources they have always relied on.

Second, the vast spread of user-generated misinformation and disinformation creates an additional burden on journalists to verify user-generated content or risk inadvertently spreading fake news. Journalists may stick to sourcing information from a familiar cast of gatekeepers in part to avoid such missteps.

Finally, the algorithmic nature of Twitter, where the platform recommends whom to follow based on users’ interests, means that it can replicate “pack journalism,” in which multiple news organizations follow the same stories using the same sources. Relevance-ranking algorithms direct journalists to content from media colleagues, politicians, and large institutions that have long served as information gatekeepers.2

Finally, the algorithmic nature of Twitter, where the platform recommends whom to follow based on users’ interests, means that it can replicate “pack journalism,” in which multiple news organizations follow the same stories using the same sources. Relevance-ranking algorithms direct journalists to content from media colleagues, politicians, and large institutions that have long served as information gatekeepers.2

So which story does the evidence from developing countries and emerging democracies support? Are journalists using Twitter to expand their access beyond their traditional professional networks and incorporate more diverse perspectives? Or is a reliance on Twitter planting journalists ever more firmly in their own echo chambers?

Both stories appear to be playing out simultaneously. Studies from Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East, as well as original research at news organizations in Mexico and Venezuela, illuminate the ways journalists in developing countries use Twitter as a newsgathering tool and gauge the extent to which they contend with—or are even aware of—problems with elite gatekeeping, the limitations of Twitter’s user base, and online misinformation.

Gatekeeping and Twitter

The central idea of the “gatekeeping theory” of media production is that before information reaches a wide audience as news, it must pass through a series of “gates” at which gatekeepers filter out some and amplify other information. Before a piece of information even reaches professional journalists, who are key gatekeepers in this process, it often first passes through the hands of publicists and government spokespeople who alert journalists to potentially newsworthy events and sources.3 Much of journalists’ awareness of events and trends in the world is thus second hand, filtered through other gatekeeping institutions and individuals.4 Generations of media scholars have argued that journalists’ reliance on elite gatekeepers has the anti-democratic consequence of limiting the range of voices in mainstream media and enabling powerful elites to control news narratives.5

In the first decade of the new millennium, some journalists and media experts expressed newfound optimism that social media could help upend the status quo of elite gatekeeping and make more perspectives publicly visible.6 Not only could ordinary people use social media to reach a wider audience, professional journalists could also use social media to circumvent the institutions and other gatekeepers on which they previously relied to set the news agenda and source information. They thought that Twitter in particular could be useful to journalists because of the platform’s predominantly public nature: By default, tweets are globally visible and no permission is needed to follow an account. A new generation of “networked journalists” could use Twitter to monitor events and create news with input from non-elite users in a more collaborative and inclusive process than traditional gatekeeping.7 This optimism peaked during the Arab Spring of 2010–12, when Twitter and Facebook became forums for mobilization and tools for fact finding about revolutions in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Syria.8

Over the past decade, social media companies have faced growing criticism. Rather than simply providing an open and neutral platform for a global conversation in which all can participate on equal terms, Twitter, Facebook, and others may be reinforcing unequal access to public attention and creating virtual echo chambers of like-minded users through opaque algorithms and moderation policies that amplify some content while hiding others. These often-automated processes can further marginalize communities that already struggle for public visibility and acknowledgement of their concerns while amplifying the voices of those with the resources and savvy to game the new system using engagement and search optimization techniques.9 Furthermore, social media platforms have enabled misinformation, conspiracy theories, and disinformation campaigns to reach the mainstream more easily and quickly than ever before.10

Case Study: Noticias.Mx

Down a side street from Mexico City’s bustling Avenida de los Insurgentes, the office of the independent news website Noticias.Mx—a pseudonym—is in operation 24/7. Noticias.Mx features both daily news and in-depth investigations. Nearly all of Noticias.Mx’s 18 journalists always have at least one Twitter tab open on their web browsers.

Twitter is central to the outlet’s reporting routines, though there is a good deal of variation in how different editors and reporters use the platform. Daily news editors are divided between units focused on soft news—entertainment, science, celebrity gossip, sport—and those on hard news—crime, politics, the economy. They must produce news articles at a fast pace, often several each per day. Twitter provides them an efficient means of monitoring other journalists covering the same topics and hundreds or thousands of figures and institutions related to their individual beats. Many of their stories aggregate this information and embed tweets from such accounts. As one editor put his newsmaking process, “I don’t produce information so much as organize it.”11

While daily news editors churn out stories by the hour, members of Noticias.Mx’s investigative reporting unit take days or weeks to research and write each of their features. Even these investigative reporters rely heavily on Twitter to monitor the outside world. Their ability to conduct field reporting is limited by scarce resources and the threats posed by Mexico’s numerous criminal organizations. On their Twitter homepages, investigative reporters find tweets on topics such as missing persons, testimonials of government corruption, or political organizing, which alert them to potential story ideas. They then use both Facebook and targeted Twitter searches to follow up with research, find sources, and request interviews. One investigative reporter described the process of covering a recent university protest movement: “I first contacted [activists] on Twitter, then visited them in person. Social media gave me an idea of what to ask and what they had already said.”12

Twitter as a Newsgathering Tool

A Noticias.Mx editor writes a story, while TV news displays a tweet above her. Photo Credit: Noah Amir Arjomand.

These observations of Noticias.Mx echo studies of newsmaking around the world. Twitter helps journalists identify newsworthy events, provides them direct sources of information in the form of tweets that they quote in news pieces, and serves as a platform to find and contact sources to interview. Studies of journalism in the Americas and Europe have found that journalists use Twitter in their daily newsgathering routines more than any other social media platform.13 There is, however, some variation across national and regional media ecosystems.14 Facebook is more central to journalists’ daily routines in sub-Saharan Africa than in Latin America, for example.15

In the case study outlined above, Noticias.Mx journalists’ usage of Facebook as a newsgathering tool is limited, despite the platform’s broad user base, in part because more of the content on the platform is by default private—visible only to a poster’s friends. On the other hand, tweets are publicly visible. Journalists are free to follow whomever they choose, rather than relying on “friending” requests that potential sources must approve. Government officials, companies, and institutions like the central bank have all adopted the platform as the primary medium for their official public communications. Celebrities, sports stars, and cultural and educational institutions also use Twitter as their channel for public announcements.

Notwithstanding the increasing prominence of Twitter in the newsroom, Noticias.Mx journalists still use news wire agencies like the Associated Press and Agencia EFE. They also still monitor competing news outlets when deciding what events and issues to cover. Twitter does not entirely set Noticias.Mx’s agenda, but it is an important tool used to complement those longer-standing methods of deciding what is newsworthy.

Case Study: Informaciones.Ve

Informaciones.Ve—a pseudonym—is a small, online-only, independent news outlet based in a half-empty shopping center in Caracas’s struggling business district. The outlet employs around two dozen staff journalists, most of them in their twenties or early thirties. Twitter plays a central role in Informaciones.Ve’s newsgathering activities. Journalists shuttle between Twitter and other web browser tabs on their laptops throughout the day, frequently refreshing their homepage feeds for the latest updates.

Despite Informaciones.Ve’s small size and limited resources, Twitter helps it avoid undue dependence on larger, more established news outlets and agencies as agenda-setters and gatekeepers. Informaciones.Ve journalists do not routinely visit other Venezuelan news websites during their shifts at the newsroom, preferring to primarily consult Twitter. The country’s political context shapes this disregard for mainstream media. Most of Venezuela’s major television stations and newspapers opposed President Hugo Chávez in the early 2000s. But, in more recent years, they have been effectively captured through intense economic and political pressure by both Chavez and the current government under President Nicolás Maduro.16 Informaciones.Ve journalists are critical of the government and view national news organizations as part of the state propaganda machine.

Informaciones.Ve journalists do, however, use Twitter to follow individual colleagues working for other news outlets, including prominent pro-Maduro journalists. On Twitter, they can find both pro-government and opposition voices. Journalists’ reliance on Twitter is unsurprising given that approximately a quarter of Venezuela’s population uses Twitter, the highest rate in Latin America.17 Informaciones.Ve reporters and editors follow accounts of state agencies, political parties, church officials, and other organizations and their leaders, as well as intermediaries and aggregators of information like the Twitter-native news service @ReporteYa.

Twitter and Sourcing Diversity

Social media extends the reach of journalists, particularly those without the time, money, and security to travel widely to conduct field reporting. Journalists who might otherwise be forced to rely exclusively on institutionalized channels for reporting the news, such as attending official press conferences or gathering information second hand from other publications, can find and communicate with sources beyond the familiar cast of elite gatekeepers. Journalists at both independent news outlets in developing countries and emerging democracies and international publications can take advantage of Twitter to diversify their sourcing. Studies of NPR and BBC coverage of revolutions and political movements in the Middle East show that Twitter-savvy foreign correspondents have developed novel techniques to find and vet information from non-elite sources.18 The platform is also relatively free from state regulation. A South African journalist interviewed for one 2014 study argued, “Twitter gets information out so quickly, it is much harder to control. This means that facts get into the public domain before any gatekeeper, whether an editor or otherwise, can stop it.”19

In Mexico at Noticias.Mx, the investigative unit actively seeks out information from non-elite sources that are not present in mainstream news. Reporters follow nongovernmental organizations and colectivos, organized groups of citizens affected by an issue that play an important role in Mexican civil society. It is common for ordinary citizens to write testimonials on Facebook and Twitter about their personal experiences with corruption or violence, which often come to the attention of Noticias.Mx reporters when quoted or retweeted by a  colectivo account. Such tweets are often the first breadcrumb leading a reporter down the path of an investigation, followed by targeted searches and phone interviews. “You can put a word into [Twitter’s] search bar and . . . find sources that nobody else has,”20 said a reporter who was in the process of investigating an economic development project in the southwest Mexican state.

colectivo account. Such tweets are often the first breadcrumb leading a reporter down the path of an investigation, followed by targeted searches and phone interviews. “You can put a word into [Twitter’s] search bar and . . . find sources that nobody else has,”20 said a reporter who was in the process of investigating an economic development project in the southwest Mexican state.

In Venezuela, Informaciones.Ve uses Twitter not only to find non-elite sources for conventional news stories and investigations, but also to crowdsource large-scale data of public interest. The unreliability of official institutions as sources for social and economic statistics has driven Informaciones.Ve to take such measures, and social media have made it possible. For example, suspicious that official figures on blackouts or gasoline shortages are unrealistic, Informaciones.Ve will announce on Twitter that it is seeking information. Followers then write to a provided WhatsApp number with the number and duration of recent power outages in their area or to tell how many hours they waited at the station to fill their gas tank.

The benefit of WhatsApp’s encrypted messaging is privacy: People can provide such information to Informaciones.Ve with less fear of reprisal than when using publicly visible media like Twitter. Twitter users and journalists have been arbitrarily arrested for public online speech, especially since the 2017 enactment of a vague but broad anti-hate speech law.21 Thus, WhatsApp provides an essential complement for Twitter that is better suited to sensitive communications.22 For example, one reporter focused on the Caracas crime beat participates in the discussion thread of a private WhatsApp group in which police officers leak information about ongoing investigations and crime reports to him and other journalists.

Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó speaks to reporters as police block him from entering Federal Legislative Palace in January 2020. Photo Credit: Noah Amir Arjomand.

In other cases, Informaciones.Ve journalists use official sources’ tweets against the grain of government control. For instance, one reporter investigated shutdowns of the Caracas metro system due to both blackouts and intentional shutdowns used to hinder anti-government protesters. She found that although government-published statistics inaccurately claimed that the system had a nearly perfect record of uninterrupted service, the Metro de Caracas official Twitter account had tweeted each time there was a shutdown. She then used these tweets to tally the interruptions and produce her count, which was much higher than the government’s.

Twitter thus helps journalists collect information from official sources without having to exchange positive coverage for access. As one Informaciones.Ve political reporter reflected, “Twitter is important for journalists from the independent media because we can’t go to official sources anymore. They won’t talk to us. They have blocked our access.”23

In each of these examples, Twitter was a tool to diversify sourcing and helped journalists collect information overlooked by, or inconvenient to, elite gatekeepers and official communication channels. Yet, paradoxically, Twitter may also be driving these same journalists into elite echo chambers in subtle ways.

Unequal Visibility on Twitter

The potential for Twitter to diversify news sourcing is undercut by forces that filter out many voices while amplifying a few for journalists. Platform usership skews elite. Even among information sources potentially available on Twitter, journalists under time pressure and concerned about online misinformation gravitate toward those accounts that appear to offer verified information—in many cases, a familiar cast of elite media gatekeepers. Conformity to long-standing sourcing and gatekeeping patterns is further reinforced by Twitter’s relevance-ranking algorithms.

An Exclusive Club

Access to the internet and electricity are requirements to use Twitter, which effectively excludes many people around the world. Internet access varies widely by region, country, and rural-urban divides. According to the latest estimates available from the International Telecommunication Union, less than half the world’s population uses the internet.24 About two-thirds of the populations of Latin America and the Middle East and North Africa are online, but less than one in five in sub-Saharan Africa. In Mexico, internet adoption was estimated in 2017 to be more than 70 percent in urban areas but under 40 percent in rural areas.25

Internet connectivity in Venezuela is nominally on a par with the regional average, but data speeds are often impractically slow, particularly from the affordable state-run service provider, CANTV (Compañía Anónima Nacional Teléfonos de Venezuela), and in rural areas. Power outages are also frequent impediments to digital communications. Blackouts are usually short-lived in Caracas, but often last for days on end in provincial cities and rural areas.26 Informaciones.Ve journalists are very aware of this problem and have given it significant news coverage.

Internet connectivity in Venezuela is nominally on a par with the regional average, but data speeds are often impractically slow, particularly from the affordable state-run service provider, CANTV (Compañía Anónima Nacional Teléfonos de Venezuela), and in rural areas. Power outages are also frequent impediments to digital communications. Blackouts are usually short-lived in Caracas, but often last for days on end in provincial cities and rural areas.26 Informaciones.Ve journalists are very aware of this problem and have given it significant news coverage.

Even among those able to log on to social media, Twitter hosts a small, self-selected minority. Studies of digital journalism across the sub-Saharan African countries of Mozambique, Kenya, Uganda, and Zimbabwe have found Twitter to constitute an “elite public sphere” that reflects the perspectives of an internationally oriented technocratic and cultural elite.27 Even in countries with widespread internet access, Twitter garners a more elite usership than Facebook.28

The selectivity of the entire network of Twitter users, then, limits the diversity of sourcing before even factoring in journalists’ particular ways of using Twitter or the platform’s interface and algorithms.

Newsgathering Routines

There is no one fixed way to interact with Twitter. A journalist may try to find novel ways to discover news sources and perspectives. Or they may “normalize” the platform by using it as a new interface for established sourcing routines.

At Noticias.Mx, the daily news editors are the ones most systematic about following the most relevant accounts to their beats, and they optimize their Twitter networks for efficiency and not diversity. “I use Twitter most for public figures,” acknowledged one editor, pointing out that many days he writes one story per hour, making it essential that he keep track of what the most prominent people are saying.29

These daily news editors also closely monitor Twitter’s trending lists, which are found on the right side of Twitter’s homepage and under a page labelled #Explore/#Explorar. Depending on a user’s settings and the tab selected, these trending sections may display a personalized list of popular keywords and hashtags or a general list of terms trending throughout Mexico as identified by Twitter’s algorithms. Editors will often click on these trending terms to display related tweets, and the top results generally come from accounts of public figures already followed by those editors, or accounts with large followings.

For daily news editors, they define a topic as newsworthy if it is trending according to Twitter, or if other news outlets or famous people are paying attention to it. One Noticias.Mx editor summarizes his process for judging newsworthiness as follows: “If I see other news media sharing and confirming something, then I will cover it.”30 Although trending lists might potentially be sources for more diverse information, the way these editors engage with the lists as well as the criteria they follow for deciding what to cover both tend to reinforce conformity with mainstream news interests. These practices and the constant pressure to quickly produce news stories make influential gatekeepers—not new and diverse voices—most visible to these journalists.

For daily news editors, they define a topic as newsworthy if it is trending according to Twitter, or if other news outlets or famous people are paying attention to it. One Noticias.Mx editor summarizes his process for judging newsworthiness as follows: “If I see other news media sharing and confirming something, then I will cover it.”30 Although trending lists might potentially be sources for more diverse information, the way these editors engage with the lists as well as the criteria they follow for deciding what to cover both tend to reinforce conformity with mainstream news interests. These practices and the constant pressure to quickly produce news stories make influential gatekeepers—not new and diverse voices—most visible to these journalists.

Not only fast-moving daily news editors, but also the investigative reporters and senior editors at both Noticias.Mx and Informaciones.Ve follow a disproportionate number of other journalists on Twitter. Approximately 30 percent of the accounts followed by Noticias.Mx employees and 38 percent of those followed by Informaciones.Ve employees belonged to individual journalists or news organizations.31 That means that when journalists at either outlet are scanning their homepages or personalized trending lists, much of the content they see has already cycled through the professional news media.

Studies of journalists’ Twitter following networks in other countries have also found that they tend to connect with other journalists and other kinds of elite gatekeepers who have traditionally guided the news agenda.32 Journalists may be over-relying on fellow media insiders for information rather than finding outsiders with fresh perspectives.

Misinformation Worries

Journalistic routines that limit sourcing diversity can stem from justifiable concerns over online misinformation. Everyone at Noticias.Mx and Informaciones.Ve is aware that much of what they read on Twitter is false or unproven, and that uncritically using such information could have negative professional consequences. “I know other journalists at other publications who have gotten in trouble for publishing rumors or fake news,” said one Noticias.Mx daily news editor.33

To avoid falling for “fake news,” journalists at both Noticias.Mx and Informaciones.Ve favor information from, and prefer to follow, accounts verified by Twitter’s blue check badge. The blue check simply indicates that the platform has verified that the account is controlled by a “prominently recognized individual or brand,” and not that the information they provide is accurate.34 Nonetheless, journalists at both outlets view blue checks as an indicator of trustworthiness.

The practice of following colleagues is also a response to the threat of misinformation: Journalists trust other journalists more than they do other sources. Though the pattern of relying on known and verified sources is understandable, it also undermines the potential for the platform to enlarge journalists’ spheres to include news sources overlooked by other news outlets.

Informaciones.Ve journalists tend to distrust not only individual unknown sources but also Twitter’s trending lists. They assume that the general Venezuelan trends list is politically manipulated using government-controlled bot and troll armies to promote pro-government hashtags and catchphrases. Analysts have indeed found evidence that both pro- and anti-government factions attempt to manipulate Twitter’s trending list through both the use of bots and coordinated campaigns.35 One communications manager at Informaciones.Ve noted that she does come up with news story ideas based on the trends displayed on Twitter, but these tend to be international stories, not news about Venezuela, which is Informaciones.Ve’s main focus.

Informaciones.Ve journalists tend to distrust not only individual unknown sources but also Twitter’s trending lists. They assume that the general Venezuelan trends list is politically manipulated using government-controlled bot and troll armies to promote pro-government hashtags and catchphrases. Analysts have indeed found evidence that both pro- and anti-government factions attempt to manipulate Twitter’s trending list through both the use of bots and coordinated campaigns.35 One communications manager at Informaciones.Ve noted that she does come up with news story ideas based on the trends displayed on Twitter, but these tend to be international stories, not news about Venezuela, which is Informaciones.Ve’s main focus.

Noticias.Mx and Informaciones.Ve are far from unique in weighing openness to new sources against trust in familiar gatekeepers. Studies of journalists’ use of social media in Belgium, Brazil, France, Kenya, and Mexico have all found that journalists trust information that colleagues or official accounts of known institutions post to Twitter more than content from ordinary, non-elite users.36

Even when journalists at Noticias.Mx and Informaciones.Ve find information from new, non-elite sources, they hesitate to use it. As a senior editor at Informaciones.Ve explains, “Twitter is dangerous . . . It is easy in real time to get something wrong, and then you get in trouble for spreading fake news.” The editor goes on to describe a verification process that depends upon their existing network of contacts: “We have a group of sources we trust, and they verify their information.”37 Noticias.Mx’s editor in chief similarly says, “We don’t publish anything until confirmed by an official news source. We will sometimes prepare a story but then wait for official confirmation from the government, a relative, or national newspapers.”38 In this context, an “official” account is one that is already within the publication’s trusted, and largely elite, network of sources and colleagues. Noticias.Mx will sometimes have a breaking news story based on information and images sourced from social media ready for publication, but if they cannot confirm the original provenance or accuracy of the information, they will delay posting the story to the website until an international news agency or one of the main national newspapers has covered it.

Noticias.Mx editors assume that those larger, better-resourced organizations have verified the authenticity of that content if they publish it. Such policies may help minimize the chance that a small news organization unwittingly spreads misinformation, but they also contribute to conformism with the dominant news media.

Algorithms and Content Moderation Policies

Twitter algorithms may reinforce journalists’ proclivity to seek information from elite gatekeepers. Relevance-ranking algorithms are designed to maximize users’ engagement and direct their attention to content and accounts based on the principle of homophily: the “birds of a feather flock together” logic that people prefer to communicate with those most similar to themselves.39 Twitter’s default ranking of content in homepage timeline feeds, trending lists, and search results are all determined by such algorithms. The logic of homophily runs directly counter to the value of information diversity. The more strongly algorithms channel journalists on Twitter toward content based on their established following networks and preexisting interests, the less likely they are to provide journalists with novel information or perspectives.

Journalists do, however, have some power to customize their Twitter interfaces to minimize the influence of these algorithms. The ranking of follow recommendations is not customizable, but that of timeline tweets and trending topics is. A user can choose to display all tweets of their followers in their timeline according to strict reverse chronology, rather than with algorithmic curation that place “top” tweets first. They can also opt to view trending topics that are not personalized but rather general for a selected country.

A Noticias.Mx editor uses the application Tweetdeck to monitor Twitter activity related to the uncovering of mass graves of victims of drug cartel violence. Photo Credit: Noah Amir Arjomand.

Few Informaciones.Ve and Noticias.Mx journalists systematically work to diversify their Twitter experiences in these ways. Some of the journalists at each outlet do use more sophisticated tools to monitor posts and trends on Twitter and Facebook, including the applications TweetDeck, CrowdTangle, and Hoaxy. Others routinely use advanced search features that allow them to narrow down results to find new sources and information that have eluded the attention of their immediate Twitter networks. Algorithmically determined timeline feeds nonetheless play an important role in shaping these journalists’ awareness of what is happening in the world on a day-to-day basis.

A thoughtful minority of journalists at both outlets are aware of and uncomfortable with the limitations of their Twitter networks in providing access to diverse and dissenting voices. As one Noticias.Mx investigative reporter specializing in women’s issues complains, “I feel like I am in a perspective bubble on Twitter. For example, on abortions I only see people who support abortion rights. I only see the other side when they trend—then I see their perspective. It is the same with LGBT and feminism issues.”40

Some journalists at both outlets have enjoyed success in using Twitter to seek out a diversity of perspectives. One Informaciones.Ve reporter factored the value of information from non-elite sources into her choices of whom to follow on Twitter: “I follow some of my own followers, not just public figures. Sometimes normal people say things that are interesting to [Informaciones.Ve] . . . Sometimes I follow anonymous people who have posted about an interesting topic I don’t know much about.”41 Both outlets have also adopted offline measures to access information from and engage with communities that are less visible to them on Twitter. Informaciones.Ve holds informal “coffee time” events, for example with Indigenous women’s collectives, at universities, and in provincial cities like Maracaibo outside of the “Caracas bubble.” Noticias.Mx has forged partnerships with independent news outlets in other cities to share content and leverage the local connections of those partners.

Conclusion

Social media platforms are having profound impacts on the practice of journalism, which now involves a complex interplay of technologies, journalistic routines, and media economies. Yet, these impacts are neither static nor uniform across news organizations. The ever-changing economic realities, political contexts, and digital infrastructures that journalists navigate all shape how they use social media as newsgathering tools. The differences between the experiences at Noticias.Mx and Informaciones.Ve illustrate how the impact of social media on journalism practice can vary greatly in different contexts.

The wealth of user-generated content available through social media potentially provides an opportunity to incorporate non-elite voices and perspectives in news coverage. But further research is needed to determine the extent to which this is truly happening, and the implications of access to a wider diversity of sources. Research is also needed to better understand whether journalists’ use of social media as a reporting tool improves the quality and plurality of news content.

The wealth of user-generated content available through social media potentially provides an opportunity to incorporate non-elite voices and perspectives in news coverage. But further research is needed to determine the extent to which this is truly happening, and the implications of access to a wider diversity of sources. Research is also needed to better understand whether journalists’ use of social media as a reporting tool improves the quality and plurality of news content.

The practice of journalism is fundamentally changing with the integration of social media technologies into the routines and practices of independent media outlets. Local and international media support organizations need to work with media outlets in developing countries to determine how best to integrate new technologies into their journalistic routines and standard operating procedures to improve efficiency, diversify sources, and publish on a greater diversity of topics. However, given the well-documented challenges of using social media for reporting, such as the sheer volume of information and the potential to publish misinformation, media support organizations also need to work with journalists and editors to develop strategies for mitigating these risks. Finally, tech companies need to better understand the implications of their design features and algorithms, not only for news audiences, but also for news producers.

The profession of journalism is fundamentally changing. Understanding how and to what effect is imperative to ensuring that evolutions in news production lead to higher-quality news and information rather than greater information disorder.

Cover Photo Credit: Esther Vargas, CC BY-SA 2.0

Footnotes

- Alejandra Hernández-Fuentes and Angeliki Monnier, “Twitter as a Source of Information? Practices of Journalists Working for the French National Press,” Journalism Practice (2020); Rachel R. Mourao and Weiyue Chen, “Covering Protests on Twitter: The Influences on Journalists’ Social Media Portrayals of Left- and Right-Leaning Demonstrations in Brazil,” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25, no. 2 (2020): 260–80; Rachel R. Mourão and Summer Harlow, “Awareness, Reporting, and Branding: Exploring Influences on Brazilian Journalists’ Social Media Use across Platforms,” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 64, no. 2 (2020): 215–35; Florence Namasinga Selnes and Kristin Skare Orgeret, “Social Media in Uganda: Revitalising News Journalism?” Media, Culture & Society 42, no. 3 (2020): 380–97.

- David R. Brake, “The Invisible Hand of the Unaccountable Algorithm: How Google, Facebook and Other Tech Companies Are Changing Journalism,” in Digital Technology and Journalism: An International Comparative Perspective, edited by Jingrong Tong and Shih-Hung Lo (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017), 25–46.

- Pamela J. Shoemaker and Timothy Vos, Gatekeeping Theory (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009).

- Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1998 (1922)).

- Herbert J. Gans, Deciding What’s News: A Study of CBS Evening News, NBC Nightly News, Newsweek, and Time (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2004 (1979)); Mark Fishman, Manufacturing the News (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980); Nick Davies, Flat Earth News: An Award-Winning Reporter Exposes Falsehood, Distortion and Propaganda in the Global Media (London: Vintage Books, 2009).

- Yochai Benkler, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006); Clay Shirky, Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations (New York: The Penguin Press, 2009); Alfred Hermida, “Twittering the News: The Emergence of Ambient Journalism,” Journalism Practice 4, no 3. (2010): 297–308.

- Ansgard Heinrich, “Foreign Reporting in the Sphere of Network Journalism,” Journalism Practice 6, no. 5–6 (2012): 766–75; Alfred Hermida, “Tweets and Truth: Journalism as a Discipline of Collaborative Verification,” Journalism Practice 6, no. 5-6 (2012): 659–68.

- Gilad Lotan, Erhardt Graeff, Mike Ananny, Devin Gaffney, Ian Pearce, and Danah Boyd, “The Revolutions Were Tweeted: Information Flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions,” International Journal of Communication 5 (2011): 1375–1405; Alfred Hermida, Seth C. Lewis, and Rodrigo Zamith, “Sourcing the Arab Spring: A Case Study of Andy Carvin’s Sources on Twitter during the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19, no. 3 (2014): 479–99.

- Tarleton Gillespie, “The Relevance of Algorithms,” in Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, edited by Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo J. Boczkowski, and Kirsten A. Foot (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014): 167–95; Tarleton Gillespie, Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018).

- Peter Dizikes, “Study: On Twitter, False News Travels Faster than True Stories,” MIT News, March 8, 2018, https://news.mit.edu/2018/study-twitter-false-news-travels-faster-true-stories-0308.

- Interview with Arjomand, December 2019.

- Interview with Arjomand, December 2019.

- Gerret von Nordheim, Karin Boczek, and Lars Koppers, “Sourcing the Sources: An Analysis of the Use of Twitter and Facebook as a Journalistic Source over 10 Years in the New York Times, the Guardian, and Süddeutsche Zeitung,” Digital Journalism 6, no. 7 (2018): 807–28; Magdalena Saldaña, Vanessa de Macedo Higgins Joyce, Amy Schmitz Weiss, and Rosental Calmon Alves, “Sharing the Stage: Analysis of Social Media Adoption by Latin American Journalists,” Journalism Practice 11, no. 4 (2017): 396–416; Mourão and Harlow, “Awareness, Reporting, and Branding.”

- Hernández-Fuentes and Monnier, “Twitter as a Source of Information?”

- Admire Mare, “New Media Technologies and Internal Newsroom Creativity in Mozambique: The Case of @verdade,” Digital Journalism 2, no. 1 (2014): 12–28; Selnes and Orgeret, “Social Media in Uganda.”

- Kara Elser, “Paper Shortage Undermines Print Media in Venezuela,” Center for International Media Assistance, November 30, 2015, https://www.cima.ned.org/blog/paper-shortage-undermines-print-media-in-venezuela/.

- “Venezuela,” Media Landscapes, n.d., https://medialandscapes.org/country/venezuela, accessed August 13, 2021.

- Maximillian T. Hänka-Ahy and Roxanna Shapour, “Who’s Reporting the Protests? Converging Practices of Citizen Journalists and Two BBC World Service Newsrooms, from Iran’s Election Protests to the Arab Uprisings,” Journalism Studies 14, no. 1 (2013): 29–45; Hermida et al., “Sourcing the Arab Spring.”

- Peter Verweij and Elvira van Noort, “Journalists’ Twitter Networks, Public Debates and Relationships in South Africa,” Digital Journalism 2, no. 1 (2014): 98–114.

- Interview with Arjomand, December 2019.

- “Freedom on the Net 2020 – Venezuela,” Freedom House, 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/country/venezuela/freedom-net/2020.

- Kate Musgrave, In Repressive Countries, Citizens Go ‘Dark’ to Share Independent News (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, December 2017), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/repressive-countries-citizens-go-dark-share-independent-news/.

- Interview with Arjomand, January 2020.

- “Individuals Using the Internet (% of Population),” World Bank, n.d., https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS, accessed August 13, 2021.

- “Freedom on the Net 2021—Venezuela,” Freedom House, 2021, https://freedomhouse.org/country/venezuela/freedom-net/2021; Interviews with Arjomand, January 2020.

- Marlen Martínez-Domínguez and Jorge Mora-Rivera, “Internet Adoption and Usage Patterns in Rural Mexico,” Technology in Society 60 (2020).

- Mare, “New Media Technologies and Internal Newsroom Creativity in Mozambique”; Benjamin Muindi, “Negotiating the Balance between Speed and Credibility in Deploying Twitter as Journalistic Tool at the Daily Nation Newspaper in Kenya,” African Journalism Studies 39, no. 1 (2018): 111–28; Hayes Mawindi Mabweazara, “Normative Dilemmas and Issues for Zimbabwean Print Journalism in the ‘Information Society’ Era,” in Online Journalism in Africa: Trends, Practices and Emerging Cultures, edited by Hayes M. Mabweazara, Okoth F. Mudhai, and Jason Whittaker (Oxfordshire, England: Routledge, 2013): 65–85; Selnes and Orgeret, “Social Media in Uganda,” 389–91.

- Nordheim et al., “Sourcing the Sources,” 821.

- Interview with Arjomand, December 2019.

- Interview with Arjomand, December 2019.

- This estimate is based on manual inspection of a random 1 percent sample of all Twitter accounts followed by employees of both outlets (N = 379).

- Folker Hanusch and Daniel Nölleke, “Journalistic Homophily on Social Media: Exploring Journalists’ Interactions with Each Other on Twitter,” Digital Journalism 7, no. 1 (2019): 22–44; Hernández-Fuentes and Monnier, “Twitter as a Source of Information?” 8–10.

- Interview with Arjomand, December 2019.

- “About Verified Accounts,” Twitter, n.d., https://help.twitter.com/en/managing-your-account/about-twitter-verified-accounts, accessed August 13, 2021.

- Michelle Forelle, Philip N. Howard, Andres Monroy-Hernandez, and Saiph Savage, “Political Bots and the Manipulation of Public Opinion in Venezuela,” Oxford Internet Institute, 2015; Erin Gallagher, “Social Media Automation & Infowars by the Venezuelan Opposition,” Noteworthy – The Journal Blog (January 30, 2019); José Luis Peñarredonda and Kanishk Karan, “#InfluenceForSale: Venezuela’s Twitter Propaganda Mill,” @DFRLab, February 3, 2019.

- Muindi, “Negotiating the Balance between Speed and Credibility in Deploying Twitter as Journalistic Tool at the Daily Nation Newspaper in Kenya,” 118–19; Steve Paulussen and Raymond A. Harder, “Social Media References in Newspapers: Facebook, Twitter and YouTube as Sources in Newspaper Journalism,” Journalism Practice 8, no. 5 (2014): 542–51. Celeste González de Bustamante and Jeannine E. Relly, “Journalism in Times of Violence: Social Media Use by US and Mexican Journalists Working in Northern Mexico,” Digital Journalism 2 no. 4 (2014): 507–23; Hernández-Fuentes and Monnier, “Twitter as a Source of Information?”; Mourão and Harlow, “Awareness, Reporting, and Branding.”

- Interview with Arjomand, January 2020.

- Interview with Arjomand, December 2019.

- Miller McPherson, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and James M. Cook, “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks,” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (2001): 415–44; Pankaj Gupta, Ashish Goel, Jimmy Lin, Aneesh Sharma, Dong Wang, and Reza Zadeh, “WTF: The Who to Follow Service at Twitter,” WWW 2013 – Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web (2013): 505–14.

- Interview with Arjomand, December 2019.

- Interview with Arjomand, January 2020.