Key Findings

West Africa sits at a critical juncture that will determine whether the coming years are spent defending against reversals in media freedom and pluralism, or moving forward toward new and lasting progress. In this context, the Media Foundation for West Africa consulted stakeholders from all 16 countries of the West Africa region on the question of how cross-border coalitions can help to promote a robust and independent press. This report puts forward a vision for such a region-wide strategy, and how it can coordinate the efforts of civil society organizations, media actors, government allies, and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Specifically, the report highlights four concrete actions that could be taken as the foundation for such a coordinated, regional strategy.

1. Formulate a network of media freedom and governance groups and enter into a memorandum of understanding with ECOWAS

2. Initiate a process and strategy for supplemental protocols and a subsequent legislative review to align national legislation

3. Commission comprehensive regional research to provide contextually relevant recommendations on media sustainability interventions

4. Integrate capacity-building efforts into broader governance agendas, including elections and peace-building

About this Report

This report is the product of consultations with a range of civil society actors; public and private media operators; media experts and academics; representatives of national media policy and regulatory bodies; and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the principal regional intergovernmental body. The Media Foundation for West Africa, a regional nongovernmental organization, conducted these consultations with support from the Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) at the National Endowment for Democracy.

This report is the product of consultations with a range of civil society actors; public and private media operators; media experts and academics; representatives of national media policy and regulatory bodies; and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the principal regional intergovernmental body. The Media Foundation for West Africa, a regional nongovernmental organization, conducted these consultations with support from the Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) at the National Endowment for Democracy.

CIMA’s support for the consultative research in West Africa is part of a wider effort. Since 2015, CIMA has been working with DW Akademie and other partners to host regional dialogues motivated by one essential question: What can cross-border coalitions do to save independent journalism from its current crisis? Following gatherings in Latin America (Bogotá, Colombia, 2015) and Southeast Asia (Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016), CIMA hosted a gathering in Durban, South Africa, in July 2017. There, 36 representatives of media organizations, civil societies, state regulators, and multilateral institutions from 15 countries across sub‑Saharan Africa came together to identify key problems, define priorities, and develop strategies to address media development gaps in the region. The results of that discussion were published in a report entitled Pathways to Media Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa.

According to the participants of the Durban meeting, West Africa provides two unique opportunities to begin implementing this agenda. When participants of the Durban consultation were asked to identify “regional institutions that have the potential to support regional cooperation to confront challenges facing media sectors in the region,” no institution was more frequently cited than ECOWAS. Second, civil society organizations and professional associations with an interest in media freedom are already well networked in West Africa, owing in part to the work of MFWA and its partner organizations in 16 countries.

With that background in mind, this report puts forward a vision for a regional approach to media development that draws from further consultations conducted in Accra, Abidjan, and Abuja, and from dialogue with ECOWAS.

Introduction

The prospects for media development in West Africa have been well served by the tide of democratization that has swept across the sub-region since the early 1990s. In nearly every country, the gains made in multiparty democratic governance have buoyed media pluralism and freedom of expression. The media have in turn stimulated public debate and spotlighted issues of governance and rule of law. Still, every tide has its counter currents. In some countries, intolerant governments have sought to breach the democratic firewalls of media’s institutional independence and viability.

The prospects for media development in West Africa have been well served by the tide of democratization that has swept across the sub-region since the early 1990s. In nearly every country, the gains made in multiparty democratic governance have buoyed media pluralism and freedom of expression. The media have in turn stimulated public debate and spotlighted issues of governance and rule of law. Still, every tide has its counter currents. In some countries, intolerant governments have sought to breach the democratic firewalls of media’s institutional independence and viability.

Though these concerns have not gone unrecognized or unanswered, the response has often been fragmented. Advocacy, capacity development, and other efforts meant to safeguard media’s public service function frequently operate at the scale of a local community or single outlet, or in the most ambitious cases, at the country level. This report puts forward the idea that a more concerted regional platform would yield multiplier benefits beyond what individual initiatives could enable. As highlighted by the regional consultation in Durban, South Africa, in July 2017, sub-Saharan Africa’s “most dramatic democratic victories have been achieved when democracy activists and proponents of media pluralism have found themselves working toward a common purpose.”1This report puts forward the idea that a more concerted regional platform would yield multiplier benefits beyond what individual initiatives could enable. As highlighted by the regional consultation in Durban, South Africa, in July 2017, sub-Saharan Africa’s “most dramatic democratic victories have been achieved when democracy activists and proponents of media pluralism have found themselves working toward a common purpose.”1 This report seeks, as such, to offer an empirically informed and contextually relevant framework for concerted and continued media development efforts in West Africa. It argues that such a regional approach to media development could do the following:

- Promote media development more comprehensively, more inclusively, and more evenly across the region

- Build upon and protect the gains already made against the threat of reversals in countries with intolerant regimes or regulatory vulnerabilities

- Unite disparate efforts with shared objectives, understandings, norms, and values to achieve synergies

- Leverage points of influence at national, regional, and global levels to push common advocacy positions on media development concerns

- Orient media development efforts in the region away from a defensive posture toward more proactive and sustainable action plans and strategies

The benefits of coalition building and collaboration are well known: They bring scale to the salience and substance of individual effort, enable the efficient and effective deployment of resources and skills, leverage the comparative advantage of individual stakeholders, and reduce duplicities and redundancies. However, building such a regional consensus agenda and platform can be onerous. It requires that concessions be made and objectives prioritized, which can seem to pit some issues against others and spark vexing discussions about the root causes of problems. These tensions and disagreements inherent in consensus building should be viewed as productive and continuous, bringing dynamism and the opportunity for renewal and change to individual initiatives.

In this spirit, stakeholders consulted through the process described in Annex I identified a number of unique opportunities, building on the will of ECOWAS, the political will of many government allies, and the regional networks of civil society organizations and media actors that have coalesced around the themes of democracy, media, and governance. This report will explore how these deliberations have pointed to four concrete actions that could be taken to foster a regional approach to media development in West Africa:

1. Formulate a network of media freedom and governance groups and enter into a memorandum of understanding with ECOWAS

2. Initiate a process and strategy for supplemental protocols and a subsequent legislative review to align national legislation

3. Commission comprehensive regional research to provide contextually relevant recommendations on media sustainability interventions

4. Integrate capacity-building efforts into broader governance agendas, including elections and peace-building

Distilling months of consultative work across 16 countries into four recommendations for action is, of course, slightly rhetorical. What these bullet points aim to convey is that a collective vision and shared strategy for media development is possible, and that the work toward this vision needs to be carried out earnestly.

The Consultative Process

This report is the product of a consultative process with a range of media stakeholders: civil society actors, public and private media operators, media experts and academics, representatives of national media policy and regulatory bodies, and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The consultations involved three subregional meetings for stakeholder engagement and data collection, and one regional validation meeting. The report puts the ideas and insights from these consultations in conversation with the evidence and experiences of past initiatives and interventions drawn from the available literature and documentation.

A full description of the process, including the methodology for facilitation, can be found in Annex I.

Building Stakeholder Synergies

Common challenges to media development

In much of West Africa, social and political communication is imbued by a particular ethic and etiquette. Among some ethnic groups in Ghana, for instance, the ritual of greeting and addressing elders and other respected persons is punctuated by expressions of decorum (sebi in Akan, taflatse in Ga, and medekuku in Ewe are all frequently used and mean “excuse me” or “I beg your pardon”) and animated abasement gestures (for example, genuflecting, crouching and clapping the hands, and even lying prostrate before the chief).2

In his celebrated classic Things Fall Apart, Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe notes, “Among the Igbo the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm oil with which words are eaten.”3 Proverbs not only enable interlocutors to express themselves with elegance, but also offer a way to employ euphemism and to thus avoid the direct, critical, and even adversarial approach that is frequently presumed (and preferred) in independent journalism reporting. This context would partially explain the relatively low tolerance threshold that political leaders in West Africa have had toward such normative principles as media pluralism, freedom of expression, and editorial autonomy.

And yet the last 25 years have been remarkable for the growth and consolidation of electoral democracies and governance institutions in much of West Africa.4 This transition, tenuous and uneven as it has been, has also been auspicious for improvements in human rights, and in particular for the liberalization of the media landscape in the various countries within West Africa. Democratic constitutional provisions (and subsequent legislation) have broken state control over centralized media systems and enabled an environment with a notional plurality of outlet ownership and greater diversity of content. In that sense, like in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa, West Africa has indeed made the greatest progress when the advocates of democracy and media freedom have worked “toward a common purpose.”5

The increasing use of the internet and the emergence of social media have also presumably democratized and diversified the processes of producing (or co-producing) the news and information available within the public sphere. Beside the professional journalist, bloggers, citizen journalists, and social media activists also produce and disseminate media content. Legacy media outlets no longer have a monopoly over information and public discourse.

While the new liberal democratic context has thus been positive for nominal growth and development in the media systems of countries across the region, there are deficits in the media’s performance and potential to contribute to accountable governance, democratic consolidation, and sustainable development.

The participants of the consultations abstracted three broad areas of focus for strategic media development interventions: media freedom; media sustainability; and media and governance. These areas can also form the foundational pillars of a policy architecture of media development in the region. Furthermore, these focal areas have implications for the actors that need to be engaged within the ECOWAS system in the implementation process.

Media freedom

The constitutions of all the countries in West Africa provide basic guarantees for free, independent, and pluralistic media, but in too many cases, with flimsy protections. When journalists express views critical of government or the political establishment, they find their rights quickly curtailed. Private media outlets in some countries are shut down on grounds of breach of ethics, while opposition voices are systematically excluded from state media in countries like Niger, Benin, and Mali.

Continuing constitutional and legislative reforms in countries like Guinea (since 2010), Liberia (especially since 2017), Burkina Faso (following the popular uprising that ousted the pernicious regime of Blaise Compaoré), and Côte d’Ivoire (since the swearing into office of President Alassane Ouattara) have been positive for media freedom and pluralism. Côte d’Ivoire in particular has been well served by the enactment of a raft of progressive legislative and institutional reforms, especially since the independent High Authority for Audiovisual Communication was established in 2011.

However, independent journalists still face the strong headwinds of criminal libel suits and imprisonment, physical reprisal, and the revocation of licenses.6 The media operate under an exacting tax regime and heavy fines for publishing “false news” or insulting the president. Similarly, Senegal presents a case of regrettable reversals since adopting the June 2012 Press Code, widely criticized for its illiberal outlook—most notably for provisions imposing crippling sanctions, including punitive fines and even custodial sentences, for the crime of libel (Articles 224 and 225 of Law 14/2017) and “threat[s] to the national security” (Article 192).7 In Nigeria, a Cybercrime (Prohibition & Prevention) Act passed in May 2015 has also been invoked to harass, intimidate, and even arrest bloggers and online journalists on the charge of “cyberstalking” (Section 24).

The tide of democratization that has swept across the region since the early 1990s and the consequent burgeoning of media outlets are also offset by worrying cases of impunity in violence against and harassment of journalists.8 This is especially pronounced during feisty electoral contests or amid threats to state security. In Mali and Niger, recent insurgencies by the Tuareg and other extremist sectarian groups have put media and journalists at risk of attack and reprisal—either for suspicion of being sympathetic to insurgents or for dishonoring doctrinal edicts.

The tide of democratization that has swept across the region since the early 1990s and the consequent burgeoning of media outlets are also offset by worrying cases of impunity in violence against and harassment of journalists.8 This is especially pronounced during feisty electoral contests or amid threats to state security. In Mali and Niger, recent insurgencies by the Tuareg and other extremist sectarian groups have put media and journalists at risk of attack and reprisal—either for suspicion of being sympathetic to insurgents or for dishonoring doctrinal edicts.

With the notable exceptions of Liberia, Nigeria, Mali, and Sierra Leone, there are no national right-to-information laws. Yet even in countries that have a national freedom of information law, concerns remain about the many systems of closure, exemption clauses, and tedious procedures for appeal. As an example, the publisher of Premium Times of Nigeria, Dapo Olorunyomi, informed those at the stakeholders meeting in Accra that in 2018 his news organization filed nearly 700 requests for information; only three responses have been received.

In spite of the provisions for freedom of expression—and even the right to information in some countries—there is also a creeping sense of a surveillance state in countries like Nigeria, Benin, Niger, and Mali, where state security operatives and party apparatchiks are used to intimidate and perpetrate violence against critical journalists. The 1993 Constitution of Guinea-Bissau provides for media pluralism and freedom of expression, but the exercise of these freedoms is hampered by a climate of fear of reprisals from security forces, political party thugs, and goons operating under the auspices of drug barons.9,10 Similarly, Niger’s democratic progress has stagnated since the adoption in 1992 of a new constitution, with the notable provisions of Article 24 (on freedoms of thought and expression) and Article 112 (on the establishment of the High Communication Council, the independent media regulatory body).11 The operationalization of these provisions has been systematically curtailed by a combination of political violence, economic stringencies, and professional weaknesses. In Sierra Leone, there has been brittle stability that is periodically tested by electoral campaign violence perpetrated by political party fanatics.

Amid these ebbs and flows, independent media in West Africa face an uncertain future, and yet industry operators, self-regulatory bodies, professional associations, and advocacy groups are not aligned in their efforts to safeguard that future. To be sure, West African media operate under a diverse array of constitutional instruments and regulatory institutions, but this diversity is an opportunity to invite introspection into the nature of existing constitutional and legislative provisions, policies, and practices.

Media sustainability

Perhaps the greatest threat to media pluralism, editorial autonomy, and the practice of professional journalism is the frail financial health of most media organizations in every country. A small advertising base and shrinking readership/circulation make the media vulnerable to capture by political and corporate interests, with the effect that most media outlets are subject to indirect control by economic and political elites that instrumentalize the media to serve their interests. These strings of control are all the more difficult to see given the lack of transparency in (especially broadcast) licensing processes and lack of access to ownership information in many countries in the region.12

Perhaps the greatest threat to media pluralism, editorial autonomy, and the practice of professional journalism is the frail financial health of most media organizations in every country. A small advertising base and shrinking readership/circulation make the media vulnerable to capture by political and corporate interests, with the effect that most media outlets are subject to indirect control by economic and political elites that instrumentalize the media to serve their interests. These strings of control are all the more difficult to see given the lack of transparency in (especially broadcast) licensing processes and lack of access to ownership information in many countries in the region.12

Even where legal protections for media freedom are strong, sustainability issues can dampen the media’s independence. For instance, while Cape Verde’s constitution directly provides for freedom of the press, as well as confidentiality of sources, access to information, and freedom from arbitrary arrest, the country’s recent string of economic recessions has left independent media struggling to survive on dwindling advertising incomes and state subsidies.13 In Sierra Leone, while the 2010 constitution guarantees media pluralism and free expression, the plethora of media outlets does not have a commensurate audience or the advertising market.14

Media’s financial sustainability in West Africa remains plagued by large operating costs, including the high price of printing stationery and other equipment costs. Media sustainability in the region is also hurt by an erratic electric power supply system and limited internet access. In addition to the poor quality of internet access, the cost of data is still prohibitive. In Benin, a recent tax on social media use increased the cost of access by up to 10 times.

The example of Nigeria is a particularly telling conundrum because the country’s large population size (approximately 130 million) invites the expectation that readership and advertising revenues would be appreciably high. And yet even the most prominent newspapers and broadcast media are not proud to faithfully declare their incomes. Amid a weak economic base, punitive fines for defamation, such as those found in Burkina Faso, have an especially potent chilling effect.

These sustainability challenges are closely intertwined with weak professional capacity. Young journalists and publishers are frequently ill-prepared for their work by institutes of higher education, and are failed again by weak or nonexistent in-house training. Along with the shrinking stream of advertising revenues, low salaries, and generally poor and unsafe working conditions, media outlets face a high rate of turnover, especially of the best-skilled practitioners, and particularly in countries like Ghana, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea-Bissau, and Cape Verde. Associations, media councils, and other key institutions promoting excellence, professionalism, and ethics face a daunting challenge in this environment. Unfortunately, the combination of poor professional practice and low wages too often results in a tendency toward mediocrity, and even mendacity.15 As one participant noted, “there is great media, but not great journalism.”

There is also a cumulative and far-reaching influence of digital technology on audience numbers and on the revenue streams of traditional media. This situation is currently aggravated by the poor quality work frequently published in the name of citizen journalism, according to participants. Media and information literacy efforts would be required to ensure that traditional media outlets that operate as online platforms do not suffer collateral damage owing to declining trust in digital media sources.

Media and governance

The media’s major contribution to democratic politics is frequently expressed with the watchdog metaphor. In this regard, the media in West Africa have been instrumental in spotlighting issues of impunity and the rule of law, exposing incidences of graft and financial malfeasance, and holding government and public officeholders to account. They have also provided the public sphere in which communicative power is distributed—in which the state is put in touch with the views and needs of citizens.

Given this important role, stakeholders suggested the need to mainstream media development initiatives into existing ECOWAS regional protocols and programs, particularly those that relate to elections, peace-building, human rights, and other related governance work. While this would assure a more coherent and comprehensive attention to media capacity-building work, it would also have the consequence of enabling the effective delivery of the democratic-governance and economic-development mandates of ECOWAS. This expectation is plausible within the frameworks of several ECOWAS conventions and provisions, including the Democracy and Good Governance Protocol, the Conflict Prevention Framework, and the Free Movement and Trade Protocols. But the imperative of the media as both instrument and index of regional political and economic development is even more demonstrably pivotal to the realization of the ECOWAS Vision 2020 of moving from the current “ECOWAS of States” to an “ECOWAS of People.”

Given this important role, stakeholders suggested the need to mainstream media development initiatives into existing ECOWAS regional protocols and programs, particularly those that relate to elections, peace-building, human rights, and other related governance work. While this would assure a more coherent and comprehensive attention to media capacity-building work, it would also have the consequence of enabling the effective delivery of the democratic-governance and economic-development mandates of ECOWAS. This expectation is plausible within the frameworks of several ECOWAS conventions and provisions, including the Democracy and Good Governance Protocol, the Conflict Prevention Framework, and the Free Movement and Trade Protocols. But the imperative of the media as both instrument and index of regional political and economic development is even more demonstrably pivotal to the realization of the ECOWAS Vision 2020 of moving from the current “ECOWAS of States” to an “ECOWAS of People.”

By contrast with the media’s theoretical place in governance, in practice the challenges described above related to media freedom and media sustainability impede the media’s potential to contribute to democracy and development in the region.

While, for instance, the media and freedom of expression have begun to flourish in The Gambia under the leadership of Adama Barrow, the specter of repressive laws left behind by Yahya Jammeh’s dictatorial regime still stalk the independent media and journalists in the country.16 The long years of civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone have resulted in systematic weakening of media institutional structures. In countries with relatively stable and freer media environments, such as Ghana, Senegal, and Benin, deficits in professional standards are revealed by ethical breaches and poor-quality output. In Togo, while there is nominally a pluralistic and vibrant media system, the potential contribution to democratic efficacy is undercut by the overbearing hand of government on the state media.17 Journalists in Niger and Mali have, for fear of recrimination, tended to exercise self-censorship on such subjects as state security and corruption, and in stories about powerful political and business elites and religious leaders.18 In Guinea-Bissau, the crisis of leadership in the last five years together with the activities of narcotic drug dealers has disabled the media system and put the work of journalists at risk.19

There is also an observed lack of appreciation for the media’s role by society and practitioners. Some journalists fail to recognize and assert the public interest role of the media as the so-called fourth estate. Consequently, the disposition and conduct of many journalists tend to erode public goodwill and support in the event that a journalist’s rights are violated. This is reinforced by the compromises that some journalists make with the politicians who pay them (and who frequently prey on those who refuse). On the other hand, the public is often unable to differentiate between good and bad journalism. Thus, within the neo-patrimonial social and cultural milieu, where, as indicated earlier, it seems ill-mannered to publicly assume an adversarial posture, journalists tend to receive public flak—not sympathy or approbation—when they fall victim to reprisals from politicians or their agents.

In many demonstrable ways, these three issues— media freedom, media sustainability, and media and governance—are mutually dependent; the realization of each is conditioned by, or consequent upon, the state and fate of the other two. For instance, a close reading of the constitutive vision of ECOWAS, as a people-oriented agency of good governance and economic development, would underline the imperative of media freedom to the realization of nearly all of its normative principles and operational mandates, most notably the protocols on democracy, human rights, and peace and security.

At the same time, one of the highlights of the stakeholder engagement processes was the revelation that a decline in the quality of journalism in many countries has the concomitant consequence of a decline in public support for media freedom, and as such, a recession in the sustainability of media institutions. In turn, the decline in public goodwill and support for media and journalism tends to detract from the competence and capacity of the media to exact the accountability of government to the public.

In this sense, good governance is both a product and guarantor of media freedom and institutional viability. Thus, a pathway to assuring the contribution of media to democratic development as an outcome of good governance is to support both the sustainability and quality of journalism, which in turn helps build and sustain public support for media freedom. Appreciating the interdependence of these three factors, and pursuing them together, may offer a possibility to reverse this vicious cycle.

Leveraging the ECOWAS System

The idea and inspiration for a regional architecture for media development flows from a number of protocols and conventions to which ECOWAS and its member states are signatories. These protocols suggest a shared vision for pluralistic, professional, and sustainable media systems in West Africa. At the international and Africa regional levels, these may be found in declarations such as these:

- The Joint Declaration on the Protection of Freedom of Expression and Diversity in the Digital Terrestrial Transition, adopted in San José, Costa Rica, May 3, 2013

- The Joint Declaration on Media Independence and Diversity in the Digital Age, adopted in Accra, Ghana, May 2, 2018

- The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (or the Banjul Charter)—a mechanism for promoting and protecting fundamental human rights and freedoms in Africa—which came into force on October 21, 1986

- The African Charter on Broadcasting, adopted at the UNESCO conference of May 3–5, 2001, held in Windhoek, Namibia

A good starting point, therefore, would be to advocate for the ratification of these declarations and conventions by member countries that have yet to do so. Secondly, a close reading of the provisions in these declarations, alongside the shared vision for a common media development policy, would offer a useful philosophical basis around which to build regional coalitions and foster reciprocities across regional bodies. As remarked upon by a participant in the Ghana meeting,passages such as these in the Joint Declaration on the Protection of Freedom of Expression and Diversity in the Digital Terrestrial Transition may be relevant:

- “the airwaves are a public and freedom of expression resource, and that States are under an obligation to manage this resource, including the ‘digital dividend,’ carefully so as best to give effect to the wider public interest”

- “States have an obligation to promote and protect the right to freedom of expression, and equality and media diversity, and to provide effective remedies for violations of these rights, including in the digital transition process”

- “if not carefully planned and managed, the digital transition can exacerbate the risk of undue concentration of ownership and control of the broadcast media”

- “the risk that a poorly managed digital transition process may result in diminished access to broadcasting services by less advantaged segments of the population (a form of digital divide) and/or in the inability of less well-resourced broadcasters, in particular local and community services, to continue to operate, undermining media pluralism and diversity”

These values become even more pressing in light of technological convergences that members of the consultative meetings acknowledged, and are having far-reaching, yet inadequately analyzed, impacts and implications on the meaning and pursuit of media freedom, media sustainability, and media and governance in West Africa.

ECOWAS itself has enacted a raft of protocols to underpin and operationalize the vision for regional integration and development, including the protocols on Free Movement, Trade, Peace and Security, Democracy and Good Governance, the Fight against Corruption, and Conflict Prevention. Each of these provisions either acknowledges or alludes to the imperative of the media, and communications generally, for the realization of their mandate.

Even more clearly illustrative is the renewed resolution and adoption in June 2007 of an ECOWAS Vision 2020 document under the tagline “ECOWAS of People.” The document asks the question “What is ECOWAS Vision 2020?” and provides an elegantly articulated answer:

In moving to adopt a common people-oriented regional vision, ECOWAS leaders recognize that past and unsuccessful Development efforts have been dominated by government and its agents. Believing strongly that West Africa’s development can best be achieved by working together within an ECOWAS of people framework, the ECOWAS Heads of State have expressed a common regional will by adopting a vision that replaces the current ‘ECOWAS of States’ with an ‘ECOWAS of People’.

Participants at the two consultative meetings in Accra and Abidjan endorsed the need to engage with ECOWAS. Participants affirmed that a worthwhile objective to pursue is for ECOWAS (as the principal intergovernmental body responsible for initiating and implementing conventions, principles, and protocols among member states) to identify with and adopt the outcomes of the consultative processes as a guide or framework toward a regional media policy. At any rate, a working relationship and indication of institutional support for the current project would be beneficial for the success of any future regional media development initiatives. Citing the need for a common right to- information legislation as an example, participants in the Abidjan meeting noted that if and when national constitutions failed to directly and comprehensively guarantee such rights, the articles of a regional instrument could be invoked to hold national governments to account.

ECOWAS engagement and entry points20

Officially, ECOWAS does not have a policy on media or freedom of expression. Officials, however, indicated general support for the CIMA-MFWA initiative with stakeholders, noting that any processes that could lead to an informed policy proposition for media development at the regional level would yield value beyond what individual endeavors could produce.

The lack of a regional media development policy was attributed principally to the structure of the ECOWAS bureaucracy, rather than a lack of conviction, in principle, about the merits of such a provision. Under the prevailing culture, protocols and conventions have tended to originate from heads of state. However, the existing reporting structure may offer an opportunity for initial buy-in at the levels of directorates and projects.21

One route would be for the communications director to draft a memorandum outlining a media development policy, which could be sent to the president of the ECOWAS Commission. The Administration and Finance Committee, which is made up of experts from ministries of finance and foreign affairs of member states, could then receive the president’s decision regarding the policy and make recommendations for the onward attention of the Council of Ministers, which is made up of nationally appointed ministers for ECOWAS affairs. After approval by the Council of Ministers, the policy would go to the heads of state, who may then adopt or reject the proposal. The implication of this approach would be the need for continued engagement and lobbying with the relevant institutional structures to begin to advocate and mainstream such an agenda into the ECOWAS institutional infrastructure.

On the opportunities for using the levels of directorates and projects as entry points of engagement, the team from the Drug Unit22 affirmed the need for ECOWAS to better engage with the media. There should be an engagement strategy that allows ECOWAS to interact with a wide network of journalists across the region, and a strategy that encourages cooperation between ECOWAS and civil society to advance the cause of media freedom. Another opportunity would be for a collection of ECOWAS news desks to disseminate information on the activities of the body, recognizing the interest of citizens to know, own, and participate in its activities. Participants suggested that the report of the consultations be shared with the commission’s vice president. This could be the basis of and opportunity for fostering a more formal and lasting relationship with ECOWAS.

According to the director of ECOWAS’s Political Affairs directorate, a revised protocol on democracy is in development, which makes a number of positive provisions on freedom of expression, elections and social media, and rule of law. The provisions acknowledge the opportunities and challenges offered by digital media and social media platforms and seek to ensure that ECOWAS citizens participate actively within the public sphere. At the global level, it will also enable ECOWAS members to participate in the production of digital cultures, and to share in the benefits of new media goods and services.

According to the director of ECOWAS’s Political Affairs directorate, a revised protocol on democracy is in development, which makes a number of positive provisions on freedom of expression, elections and social media, and rule of law. The provisions acknowledge the opportunities and challenges offered by digital media and social media platforms and seek to ensure that ECOWAS citizens participate actively within the public sphere. At the global level, it will also enable ECOWAS members to participate in the production of digital cultures, and to share in the benefits of new media goods and services.

There is a general recognition of the opportunities and benefits to member citizens, and to the business competitiveness of the region as a whole, of a digital single market that, for instance, enables transborder access to media content and information online. This could not only open opportunities for peer monitoring on good governance and public participation, but also promote the cultural and economic values of West African arts, heritage, tourism, education, and literary creations. Advocacy efforts for media policy should take advantage of these potentials.

Finally, ECOWAS has a role to play in relation to the impact of digital communication technologies on access to information and the sustainability of journalism. What policies can make internet and digital media software and tools affordable and accessible to regional media organizations? How can ECOWAS help ensure that quality content is accessible and affordable through digital platforms to underserved audiences, like rural residents, the youth, and women? Answers to these complex questions are yet to come, but encouragingly ECOWAS has begun to take a more proactive role in safeguarding the internet as a democratic and commercial resource. It is partially on account of this that ECOWAS is currently collaborating with information and communication technology (ICT) ministries of member states to equip them with the newest ICT tools and knowledge. Under this scheme, member states are able to request and receive equipment and training for select groups in especially deprived communities. Benin and Cape Verde are examples of countries that have benefited from this project. ECOWAS should continue to build upon these efforts.

Validation and Recommendations

As indicated at the beginning of this report, the intractable challenges to media development and sustainability in West Africa are partly rooted in a checkered political history and neo-patrimonial cultural milieu. The tenor of the validation meeting generally reflected this realization. Participants echoed the need for concerted and continued collaboration among stakeholders in engendering a social, political, and economic environment that supports and sustains media development efforts in the region.

The meeting was attended by participants from a cross section of media actors, activists, and associations. Participants unanimously endorsed the draft report of the consultative meetings in Accra, Abidjan, and Abuja on the proviso that the final report reflect or address issues of concern, clarification, and elaboration that members raised. This section presents a synthesis of the outcome of the validation meeting and recommendations for next steps in operationalizing the priorities and strategies for media development in West Africa.

Concerns and clarifications

There was consensus on the challenges to media development and the imperative of building stakeholder synergies to address them. What seemed to divide opinion was the pecking order of the challenges in terms of priority. These ongoing debates reflect the challenge of building a regional consensus agenda and platform, but also how the effort can usefully surface fundamental assumptions underpinning media development work.

There was consensus on the challenges to media development and the imperative of building stakeholder synergies to address them. What seemed to divide opinion was the pecking order of the challenges in terms of priority. These ongoing debates reflect the challenge of building a regional consensus agenda and platform, but also how the effort can usefully surface fundamental assumptions underpinning media development work.

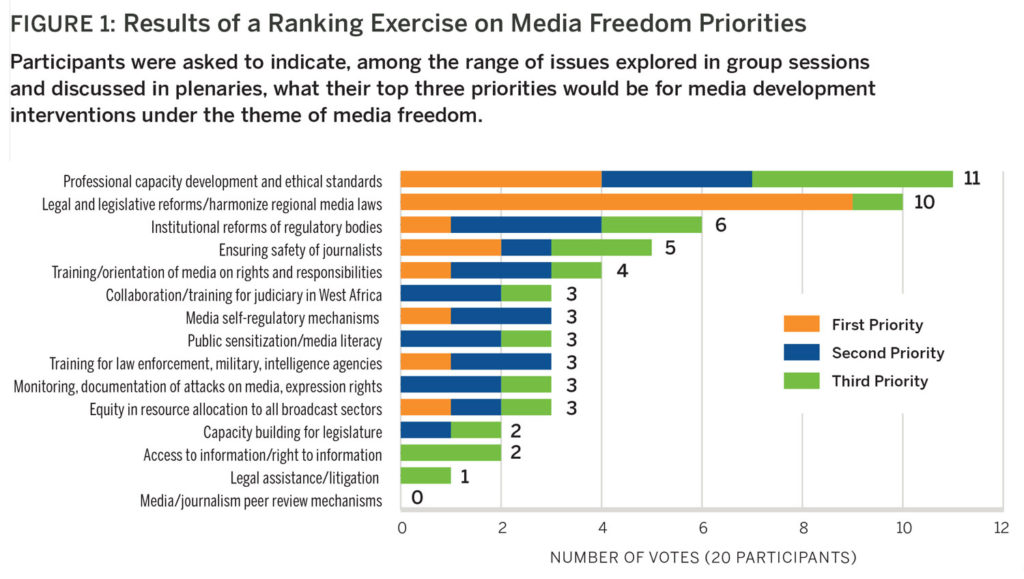

As an example, a participant from Nigeria, with a media rights advocacy orientation, was surprised that under the theme of “media freedom,” stakeholders gave top priority to the issue of “professional capacity development and ethical standards” (see Figure 1 for the list of rankings); he felt the priority in that theme should have been “ensuring safety of journalists.” On the other hand, a participant from Benin was adamant that a true reflection of the objective conditions and needs of the media would privilege “legislative reforms and financial assistance for media” above any other attribute or indicator of media freedom.

Participants also emphasized that the financial constraints that continue to assail media institutions and practitioners in the region are paramount. No amount of professional training can overcome the incentives of pecuniary and parochial gain that perversely promote partisan and sectarian interests over the public good. As one participant from Ghana emphasized, the media have not been immune to corruption, leading to public by participants of the consultative meetings that sustainability, professionalism, and

protection of journalists are indeed all intricately intertwined.

The concern about the extent to which the media serve and reflect the needs ofsociety—including those of social, cultural, and economic minorities—was echoed by many of the participants at the consultations and validation meeting. From the perspective of those working with marginalized communities, this question also raises the need to consider noncommercial funding models that permit the proliferation of citizens’ media and forums for genuine self-expression, good governance, and democratic development. The meeting also observed the question of media ownership as an important factor in addressing media development needs and priorities. According to participants, most media organizations are owned by politicians and their cronies. This, they noted, affects the principles and pursuit of journalistic objectivity and institutional autonomy.

The validation meeting also acknowledged new threats to media development and sustainability that are posed by digitalization and the gravitation of the younger generation of West Africans toward social media platforms and tools. This, it was noted, has resulted in more diffuse forms of harassment and censorship. This concern is illustrated by the contribution of a participant from Nigeria, who expressed the view that with the advent of technology and social media, media practitioners are now faced with trolls and other cyberbullying tactics; this is in stark contrast to the blatant physical assaults typically perpetrated by agents of intolerant governments and powerful individuals.

The meeting reiterated the need to harmonize media policies and laws that promote good governance and democracy, particularly as may pertain to regional and global protocols and conventions. To illustrate, a participant noted that the office of the special rapporteur on freedom of expression and access to information in Africa has, in consultation with civil society, promulgated a model Law on Access to Information in Africa, which the African Union has already adopted. The popularization and adoption of the model law by countries in the West Africa subregion will go a long way in helping countries within the region establish a common freedom of information legal framework. To this end, they recognized the valuable contributions of ECOWAS and called for more formal engagements and collaboration around policies and programs of mutual benefit.

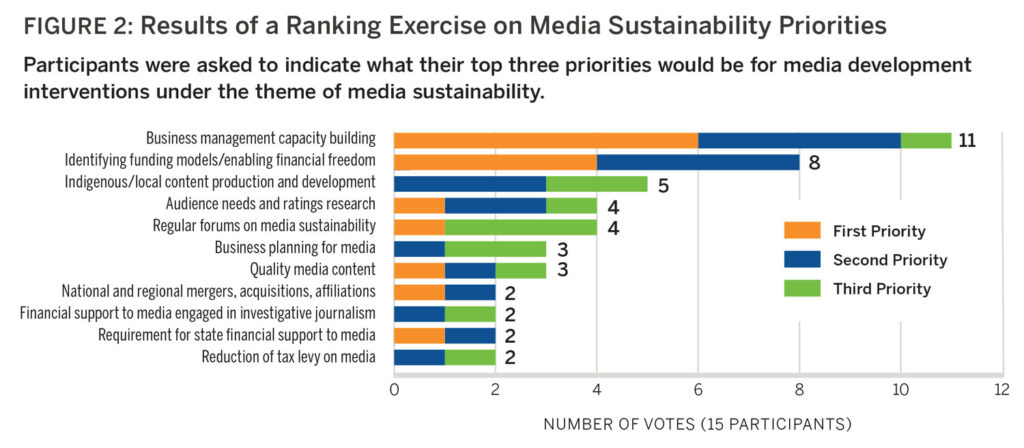

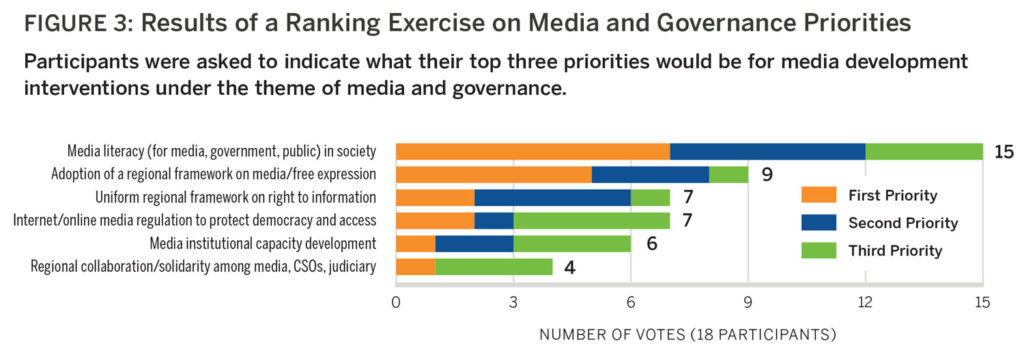

In a subsequent side meeting with a director at the ECOWAS Commission, the role of the media as stakeholders in advancing the vision of ECOWAS—specifically, to promote good governance and economic development—was acknowledged. According to the official, ECOWAS was doing many remarkable things for which there was insufficient public awareness, due principally to inadequate appreciation and engagement with the media by agencies of the commission. In the particular areas of conflict prevention and free and fair elections, the recent political transitions in The Gambia and Liberia and the positive contribution of the media to those outcomes, were noted. It was also mentioned that the ECOWAS commissioner had identified the lack of a media strategy to project the commission’s programs and projects, and had suggested the need for mistrust and the observed lack of empathy for journalists in the event of physical attack or punitive legal sanctions. This reinforces the observation each of the directorates/departments of the commission to have a focal media liaison. The consultative process involving anglophone and francophone stakeholders for this report is, therefore, an initiative that should receive the positive support of the ECOWAS Commission. The director also encouraged the MFWA to formalize relationships with the ECOWAS Commission through a memorandum of understanding; as he acknowledged, some steps toward this MOU had already been initiated. The concerns and observations raised above provided feedback for clarifying or elaborating some elements in the draft report, such as collapsing some of the attributes under each priority theme and including the individual indications of first, second, and third choices. But the more substantive observation, which was explained to participants, is that the factors of media sustainability are really interrelated—and that a comprehensive, coherent approach that treats topics as points of emphasis, rather than mutually exclusive concerns, may be required to enable sustainability of media development outcomes.

In a subsequent side meeting with a director at the ECOWAS Commission, the role of the media as stakeholders in advancing the vision of ECOWAS—specifically, to promote good governance and economic development—was acknowledged. According to the official, ECOWAS was doing many remarkable things for which there was insufficient public awareness, due principally to inadequate appreciation and engagement with the media by agencies of the commission. In the particular areas of conflict prevention and free and fair elections, the recent political transitions in The Gambia and Liberia and the positive contribution of the media to those outcomes, were noted. It was also mentioned that the ECOWAS commissioner had identified the lack of a media strategy to project the commission’s programs and projects, and had suggested the need for mistrust and the observed lack of empathy for journalists in the event of physical attack or punitive legal sanctions. This reinforces the observation each of the directorates/departments of the commission to have a focal media liaison. The consultative process involving anglophone and francophone stakeholders for this report is, therefore, an initiative that should receive the positive support of the ECOWAS Commission. The director also encouraged the MFWA to formalize relationships with the ECOWAS Commission through a memorandum of understanding; as he acknowledged, some steps toward this MOU had already been initiated. The concerns and observations raised above provided feedback for clarifying or elaborating some elements in the draft report, such as collapsing some of the attributes under each priority theme and including the individual indications of first, second, and third choices. But the more substantive observation, which was explained to participants, is that the factors of media sustainability are really interrelated—and that a comprehensive, coherent approach that treats topics as points of emphasis, rather than mutually exclusive concerns, may be required to enable sustainability of media development outcomes.

Participants were also reminded that the findings as presented reflect the collective voice of stakeholders in the rounds of consultative meetings. Therefore, the particularities of individual organizations or countries must be considered without presenting an obstacle to collective outcomes. The validation meeting was an opportunity to collectively deliberate and, despite continued debate, to reach consensus on a path forward.

Actionable next steps

The following issues should be considered in any subsequent plans for media development activity in the region:

1. Formulate a network of media freedom and governance groups and enter into an MOU with ECOWAS. As an immediate objective, stakeholders should constitute themselves into a network that collaborates with relevant institutions and departments within the ECOWAS Commission, particularly on programs that require media coverage and publicity. In the medium term, MFWA should pursue steps already underway to enter into a formal relationship with the Commission by signing a memorandum of understanding. The ultimate goal should be to advocate, engender, and orient the ECOWAS Commission toward the formulation of policy, and/or mainstreaming of media development initiatives into its programs.

2. Initiate a process and strategy for supplemental protocols and a subsequent legislative review to align national legislations. The network of stakeholders should initiate engagements with the ECOWAS Commission toward harmonizing and adopting a regional legislative framework. Such a framework would then guide the formulation, reform, or revision of national-level media laws and policies. A useful example would be to advocate for the ratification and operationalization of relevant existing protocols and charters, such as the model Law on Access to Information in Africa. Such initiatives and interventions must resonate with the three key thematic areas of priority as identified by participants: media freedom, media sustainability, and media and governance.

3. Commission comprehensive regional research to provide contextually relevant recommendations on media sustainability interventions. The findings of such a study should inform funding initiatives as well as guide media managers and owners on decisions about appropriate economic models, audience engagement strategies, and multimedia and cross-platform opportunities within the digital sphere. The empirical evidence should also inform strategies of continued advocacy and awareness-raising among stakeholders of media, civil society, government, legislature, judiciary, and the public about the imperative of media for democracy and development.

4. Integrate capacity-building efforts into broader governance agendas, including elections and peace-building. Relevant regional media development actors and ECOWAS should leverage the symbiotic benefits that are offered by a closer working relationship. Through such a relationship, while ECOWAS would be encouraged to more directly integrate media development activities into its governance programs, a strengthened media system would be more useful in contributing to the outcomes of ECOWAS’s democratic and economic development objectives. In addition, stakeholders must undertake capacity-building interventions—for media organizations to improve their institutional infrastructure and management practices and for journalists to improve their professional practices and ethical standards. Such initiatives must learn from and avoid any approaches that have led to unsatisfactory outcomes for capacity-building activities in the past. They must also respond to the realities that are native to the material conditions and needs of media and practitioners in their locales rather than merely mimic normative prescriptions.

This consultative process has affirmed a willingness and capacity in West Africa to promote media development at a regional level. More than that, the process has identified four key activities that would form the pillars of a regional strategy that marries the efforts of a growing network of media actors and civil society organizations with ECOWAS’ authority and influence. The benefits of this regional approach are clear, and needs have never been more urgent. West Africa sits at a critical juncture that will determine whether the coming years are spent defending against reversals in media freedom and pluralism, or moving forward toward new and lasting progress.

Realizing this vision will require commitment by groups on the ground, and that commitment can only be sustained if those groups remain integral to the formulation of regional strategies. Success in this agenda will also require champions within ECOWAS and member state governments that can help to maintain media pluralism and independence at the top of the governance and development agenda. In addition, regional initiatives will need international partners who are willing to provide assistance that further strengthens the ability of the region to shape and pursue its own media development ambitions.

Annex 1: Methodology

This is not the first report of its kind. Within the last two decades, there have been a number of initiatives and interventions in the region aimed at addressing the challenges facing media development and helping position the media as effective enablers of good governance in the region. Such past and ongoing activities have achieved modest gains, but several significant challenges remain. The persistence of these barriers raises a number of questions that formed the basis of the three consultative meetings:

1. To what extent are national and regional media policies/ legislation consistent with each other, and with international norms and benchmarks?

2. What is the implication of the sources and models of media revenue generation in West Africa for the situation and sustainability of media?

3. What is the state of professional capacities and in the practice of journalism in West Africa—including issues of ethics and objectivity, editorial autonomy and standards, training levels, and equipment needs?

4. To what extent are the outcomes of media development efforts in the past consistent with intended ends, especially in their contribution to good governance and the democratic dividend?

5. What opportunities and threats are posed by, or to, social media for advocacy and engagement of citizens with the pillars of political power and the structures of social mobility in West Africa?

6. What are the synergies with ECOWAS that can be leveraged to promote common media development policies and strategies in West Africa?

7. What are the biggest challenges to media development in West Africa and what could be the best strategies for tackling them?

The report sought to provide empirical answers and informed insights into these questions, and flowing from that, to synthesize the emergent issues into conclusions and their interlinking recommendations.

Discussions and inputs revolved around the following key topics:

- Media laws and policies

- Media professional standards

- General media capacity

- Media business and sustainability

- Safety of media/journalists

- Media ownership and independence

- Right to information and the media

- Key strategies for media development in West Africa

- Strategies for regional collaboration (including with ECOWAS) for media development in West Africa

- Prevailing political, economic, and cultural factors that may help or hurt any such media development endeavors

Three consultations and one validation meeting were convened and conducted around the following three goals:

1. To acknowledge the many positive and promising institutions and initiatives that already exist for media development in West Africa

2. To understand and account for any context peculiarities that inform current media development efforts at national and regional levels of engagement

3. To identify gaps and define priorities for deploying tailored interventions for future media development in West Africa

Three subregional stakeholder engagements and data collection meetings were held in Accra, Abidjan, and Abuja. The Accra meeting was for anglophone West Africa and involved participants from Ghana, Nigeria, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and The Gambia. The Abidjan meeting was for francophone West Africa and involved participants from Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Togo, and Niger. The consultation in Abuja was held with ECOWAS officials.

These meetings were used to engage with stakeholders and experts on the initiative and also as data collection platforms. The meetings were held in the form of general discussions on the overall media sector in the region, challenges, opportunities, priorities, and effective strategies for addressing the challenges. There were breakout sessions for small groups to brainstorm on specific issues and provide feedback at plenary sessions.

For the Accra and Abidjan meetings, target participants from the non-host countries included the heads of the respective MFWA national partner organizations and prominent media experts. Participants from the host countries included well-known editors, academics, and representatives of the media regulatory bodies.

The meeting in Abuja was held with relevant officials within the ECOWAS system. ECOWAS plays a critical role in governance, peace and security, and overall regional development. The need to strengthen and enable the media to support such regional development efforts has been implicit in much of its policies and practices. It was therefore important to engage with ECOWAS in such a regional media development initiative for three reasons: first, to seek its institutional buy-in; second, to seek the views and perspectives of key individuals at some of the relevant departments at the ECOWAS Commission on the regional media landscape; and third, to seek its collaboration and cooperation in the implementation of a potential project resulting from the regional study.

A fourth and final meeting was held in Accra to present a draft report and to seek input and validation of the findings, conclusions, and recommendations from stakeholders. This final meeting brought together key stakeholders in media development from all countries in the region as well as ECOWAS.

Photo Credits:

Banner: © Tommy Trenchard / Alamy Stock Photo

Gambian President: © ZEN – Zaneta Razaite / Alamy Stock Photo

Nigerian Social Media Week: © Johnny Greig / Alamy Stock Photo

All other photos courtesy of Media Foundation of West Africa (MFWA)

Footnotes

- H. Wasserman and N. Benequista, Pathways to Media Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: Reflections from a Regional Consultation (Washington: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017).

- G. Tietaah, “Abusive Language, Media Malaise and Political Efficacy in Ghana,” In K. Ansu-Kyeremeh, A. Gadzekpo, and M. Amoakohene (eds.), A Critical Appraisal of Communication Theory and Practice in Ghana, University of Ghana Reader Series (Accra: Digibooks, 2015).

- C. Achebe, Things Fall Apart (New York: Anchor, 1994), ch. 1, para. 14. First published in 1958.

- Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA), West Africa Freedom of Expression Monitor, April–July 2018; E. Okoro, “Mass Communication and Sustainable Political Development in Africa: A Review of the Literature,” Studies in Media and Communication 1, no. 1 (2013): 49–56.

- Wasserman and Benequista, Pathways to Media Reform in Sub‑Saharan Africa.

- BBC, African Media Development Initiative: Research Summary Report (Strand, London: BBC World Service Trust, 2006).

- Loi N°14/2017 portant Code de la Presse. See MFWA, “Senegal’s New Press Code: A Step Forward, Two Steps Backwards,” July 12, 2017, http://www.mfwa.org/senegals-new-press-code-a-stepforward- two-steps-backwards/.

- MFWA, West Africa Freedom of Expression Monitor.

- United Nations Security Council, Report of the Secretary- General on Developments in Guinea-Bissau and on the Activities of the United Nations Peacebuilding Support Office in That Country (September 28, 2007), para. 25–26, https://undocs. org/S/2007/576; D. O. Regan and P. Thompson, Advancing Stability and Reconciliation in Guinea-Bissau: Lessons from Africa’s First Narco-State (No. ACS-SR-2), National Defense University (Fort McNair, Washington: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2013), https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a600477.pdf.

- G. S. Abdourahmane, The Law and the Media in Niger (Accra: MFWA, 2009).

- Abdourahmane, The Law and the Media in Niger.

- G. Ogola, “African Journalism: A Journey of Failures and Triumphs,” African Journalism Studies 36, no. 1 (2015): 93-102.

- Freedom House, “Cape Verde,” Freedom of the Press Index Country Report for 2015, 2015, https://freedomhouse.org/report/ freedom-press/2015/cape-verde; B. Baker, “Cape Verde: The Most Democratic Nation in Africa?” The Journal of Modern African Studies 44, no. 4 (2006): 493-511.

- BBC, “Sierra Leone Profile – Media,” August 29, 2017, https:// www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14094381.

- R. Asante, M. Norman, E. Tzelgov, and S. I. Lindberg, Media in West Africa: A Thematic Report Based on Data 1900–2012, V-Dem Thematic Report Series, No. 1 (Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute, October 2013).

- E. Sanyang and S. Camara, The Gambia after Elections: Implications for Governance and Security in West Africa (Senegal: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2017); N. Hultin, B. Jallow, B. N. Lawrance, and A. Sarr, “Autocracy, Migration, and The Gambia’s ‘Unprecedented’ 2016 Election,” African Affairs 116, no. 463 (2017): 321-340; MFWA, West Africa Free Expression Monitor: Jan-Mar 2017, 2017, http://www.mfwa.org/wp-content/ uploads/2017/06/Freedom_Monitor-Jan-March-2017.pdf.

- K. S. M. Attoh, The Law and the Media in Togo (Accra: MFWA, 2012).

- International Media Support, MFWA, and Panos West Africa, Media in Mali Divided by Conflict (Denmark: International Media Support, January 2013), https://www.mediasupport.org/ wp-content/uploads/2013/02/media-in-mali-divided-by-conflict- 2013-ims2.pdf; Abdourahmane, The Law and the Media in Niger.

- United Nations Security Council, Report of the Secretary-General on Developments in Guinea-Bissau; D. E. Brown, The Challenge of Drug Trafficking to Democratic Governance and Human Security in West Africa (Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 2013).

- Based on the mandate of the consultative meetings, four meetings were held with the relevant officials and directorates of ECOWAS on September 26 and 27 at the ECOWAS Commission in Abuja, Nigeria. Individuals and teams that were consulted included those from the Communications and Political Affairs directorates, and the head of the Community Computer Center project. A fifth meeting that was planned with the director of information and communication technology policy was eventually abandoned due to challenges with securing the availability of the director (notwithstanding the prior undertakings). Questions were instead sent to him by mail, but the response is yet to be received.

- Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), “Governance Structure,” http://www.ecowas.int/about-ecowas/ governance-structure/; ECOWAS CEDEAO, ECOWAS Vision 2020: Towards a Democratic and Prosperous Community (Abuja, Nigeria: ECOWAS Commission, June 2010), http://araa.org/sites/default/ files/media/ECOWAS-VISION-2020_0.pdf.

- The Drug Unit of the Political Affairs directorate had occasion to leverage the media network of the ECOWAS Civil Society Platform on Transparency and Accountability in Governance (ECSOPTAG). MFWA hosts the secretariat of ECSOPTAG and has Sulemana Braimah (executive director, MFWA) as secretary general.