Introduction

When Mali in 1991 ended more than two decades of one-party rule, it embraced media freedom and pluralism as an essential part of its democratic transition. For two decades the country was considered a success story of democracy in Africa. The greater freedom enjoyed by the media and the flourishing of radio stations in the country was seen as part of a wider growth of independent and plural media in Africa during the 1990s, following earlier periods of control over the media by post-colonial governments.

Unfortunately, the link between media and democracy in Mali works both ways: reversals to Mali’s democratization have frequently been accompanied by setbacks to media freedom. In 2000, the government passed a law allowing journalists found guilty of defamation to be fined or imprisoned, and journalists came under pressure to self-censor reports on sensitive topics. And when a coup d’état in 2012 and conflict in the country’s north threatened the country’s democracy, the space for media was further constrained. According to Freedom House, in the country’s north, it is dangerous for journalists, bribery of journalists is commonplace, and working conditions for journalists have worsened.

Everywhere in the world, democracy and press freedom have been natural companions, but as the case of Mali illustrates so well, the relationship between the two has been closely entwined in sub-Saharan Africa. In the struggles for independence from colonial rule, in the wave of post-colonial movements that ended military regimes and dictatorships, and in the efforts today to keep governments accountable, the demands for press freedom, citizen voice, and pluralism have frequently been at the vanguard. Conversely, as democratic institutions in the region have been slowly hollowed out in recent years by colluding political and economic elites, so too have we seen media pluralism eroded by the influence of the powerful: authoritarians have left standing the facade of democratic institutions and press freedoms in the region, while disabling them from within.

Fatou Jagne-Senghor, director of Article 19 West Africa, speaks with some of the other participants of the consultation in Durban.

This report lays out a vision for how the continuing struggle for vibrant, independent, and plural media systems in the region might more effectively bolster efforts of democratic revitalization. The report draws on the input of 36 experts in media and governance from 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa who met in Durban, South Africa, in July 2017, and it deepens the insights and ideas that came from this group by documenting previously successful media reforms in sub-Saharan Africa.

History reveals that the goals of both deepening and strengthening democracy in the region go hand in hand, but also that the region’s most dramatic democratic victories have been achieved when democracy activists and proponents of media pluralism have found themselves working towards a common purpose. Still, globalization and the rise of digital communication technologies have also created new challenges and opportunities for media and democracy in the region that will require new coalitions and advocacy strategies.

This document puts forward a strategic vision for international collaboration and solidarity in sub-Saharan Africa in support of media pluralism; it does not intend to suggest a blueprint or template, but is a call for more coordinated and strategic action. The future of media systems will be determined either by those acting in self-interest or by those who value pluralism, and the implications for democracy in the region will be profound.

ABOUT THIS REPORT

In July 2017, a group of 36 experts in media and governance from 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa met in Durban, South Africa, to discuss strategies for confronting the growing challenges to media pluralism in the region.

Facilitated by DW Akademie and CIMA, the participants reached an agreement at that two-day gathering on the need to build a multistakeholder network of non-state actors working with governments, parliamentarians, regional and international bodies, regulators, and others to support a conducive legal, regulatory, and economic environment for media and to defend independent voices, especially when under attack. Participants further identified four sets of objectives that could be achieved by such a network: cross-country solidarity for independent media and civic space; the financial sustainability of media outlets; the influence of African media stakeholders in digital policies and debates; and improved media literacy and professionalism. Perhaps most importantly, participants began to trace the potential pathways to these goals.

This report builds on those discussions and draws from research from across the continent to put forward a vision of how broader cross-country coalitions in sub-Saharan Africa could create pathways—through the complex political, economic, and technological challenges of the day—to media systems that could support the revitalization of democracies in the region.

Gains in media freedom now under threat

Media and the third wave in sub-Saharan Africa

The great advances for freedom of the media in sub-Saharan Africa occurred as the third wave of democratization 1 swept across the continent’s shores. The 1991 Windhoek Declaration—a call for media freedom drafted by African journalists, later endorsed by the United Nations’ cultural organization, UNESCO, and seen as a pivotal moment for media development in the region—came as Benin (1991), Mali (1992), Ghana (1992), Malawi (1994), South Africa (1994), and other countries were shedding oneparty states and military regimes in favor of more open, competitive politics. These transitions were not always immediate or even successful. In many of these cases (Kenya’s 1992 elections being a prime example, with the 2017 elections in this country nullified by the courts), incumbents continued to abuse their power to manipulate electoral results for years to come. Nonetheless, the Windhoek Declaration clearly marked the beginning of more than a decade of steady progress in sub-Saharan Africa towards greater democratic rights and media freedom. Kwame Karikari, a leading scholar of African media and the founder of the Media Foundation for West Africa, wrote years later of the transformation he had witnessed in press freedom during this wave of democratization:

The media boom of the late 1980s and early 1990s, accompanying the movement for democratic reforms in Africa, transformed the continent’s media landscape virtually overnight. It ended near-absolute government control and monopoly and ushered in a vibrant pluralism. Suddenly the streets of Africa’s capitals were awash with newspapers. The ‘culture of silence,’ imposed first under colonialism and then by post-colonial military dictatorships and autocratic one-party states, was rudely broken. 2

More important, perhaps, than the growth in private, independent newspapers in this period was the growth of private and community radio and television stations, which occurred even in states that had previously maintained strict control of the airwaves. The Windhoek Declaration’s appeal for the region’s state broadcasters to be transformed into public broadcasters has not been successful, but private broadcasting was at least allowed to flourish. In West Africa, for instance, by 2004 all but one country, Guinea, permitted the private ownership and operation of broadcasting.3 In the east, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda developed vibrant private broadcasting industries in this period. In South Africa, media ownership diversification has not been so much in quantity as in kind; four companies continue to control much of the country’s broadcast and print media, though the end of apartheid did help break the hold of white South African investors over those companies. 4 And, despite recurring instances of interference in editorial decision-making, the advent of democracy saw the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) change from a state to a public broadcaster.

The diversification of the media sector across the sub-Saharan continent was accompanied by better legal and institutional frameworks in support of media freedom. The new constitutions adopted in the region in the last three decades have all enshrined some right to the freedom of expression, though many constitutions still retain subclauses that impose excessive restrictions on that right related not only to national security, but to public order, morality, insults, or other murky or vague notions that have been used to criminalize critical journalism.

Still, by the end of the 1990s, though many legal provisions in the region pertaining to media and freedom of expression failed to measure up to international standards, the decline in the legal and extralegal harassment of journalists in the region, and the adoption of the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression in Africa by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights in 2002 seemed to confirm a sense of momentum in the region towards greater media freedom and pluralism.

The slow erosion of democracy and press freedom

But as sub-Saharan Africa’s democratization in the 1990s went hand in hand with progress in media freedom, the onset of a so-called democratic recession 5 following the turn of the millennium reversed some of the gains. Between 2009 and 2017, the average press freedom score for countries in sub-Saharan Africa 6 worsened, moving from 58.4 to 59.7 (where one is the best possible score, and 100 the worst). But more telling in some ways is the growth of “partly free” countries in the region. The designation “partly free”—as distinct from “free” and “not free”—describes countries that are electoral democracies in the narrowest sense, but lacking in fundamental civil liberties. The number of countries in that category in the region rose from 18 to 26 between 2009 and 2017, as the conditions in some free countries deteriorated (Ghana, Mali, Namibia) and the conditions in some unfree countries improved (Madagascar, Niger). This convergence towards

But as sub-Saharan Africa’s democratization in the 1990s went hand in hand with progress in media freedom, the onset of a so-called democratic recession 5 following the turn of the millennium reversed some of the gains. Between 2009 and 2017, the average press freedom score for countries in sub-Saharan Africa 6 worsened, moving from 58.4 to 59.7 (where one is the best possible score, and 100 the worst). But more telling in some ways is the growth of “partly free” countries in the region. The designation “partly free”—as distinct from “free” and “not free”—describes countries that are electoral democracies in the narrowest sense, but lacking in fundamental civil liberties. The number of countries in that category in the region rose from 18 to 26 between 2009 and 2017, as the conditions in some free countries deteriorated (Ghana, Mali, Namibia) and the conditions in some unfree countries improved (Madagascar, Niger). This convergence towards

partly free reflects a trend that has been remarked upon repeatedly in reports that seek to take stock of press freedom in the region: the growing tension between the rights enshrined in laws and treaties, and the systematic violation of those same rights in practice.

Like elsewhere in the world, the threats to press freedom in Africa are no longer confined to overt acts of intimidation or censorship by the state, but are now emanating from more subtle forms of media capture, in which political elites, frequently in collusion with oligarchs, use a combination of political and economic power to cow regulators and control media narratives. 7 While capture has always been a threat, media systems are now more vulnerable than ever to these forms of manipulation, owing to the disruption and change to the journalistic business models brought by new digital technologies.

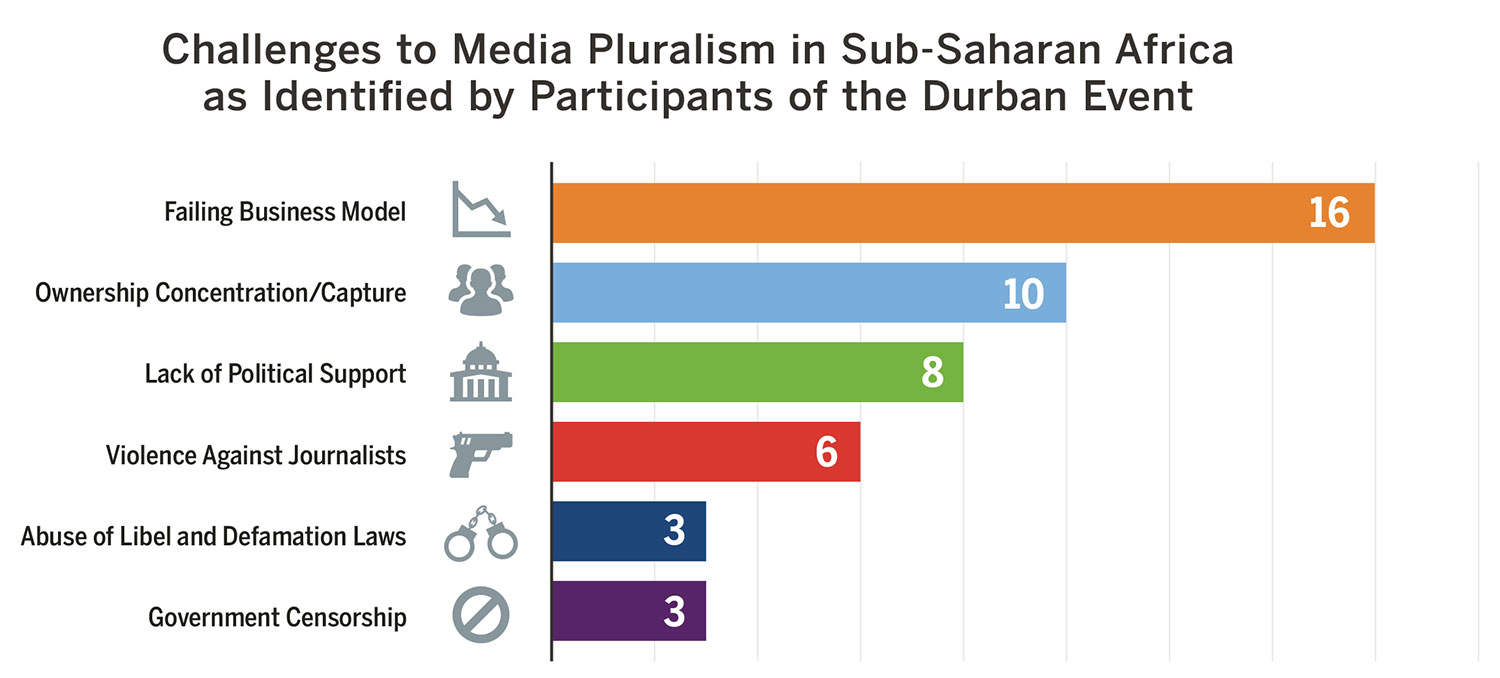

Participants in the July 2017 consultation in Durban agreed that African media houses are especially susceptible to capture by powerful or wealthy elites given how many of the region’s media outlets were already struggling with financial sustainability even before the rise of digital communication technologies began to threaten traditional advertising revenue.

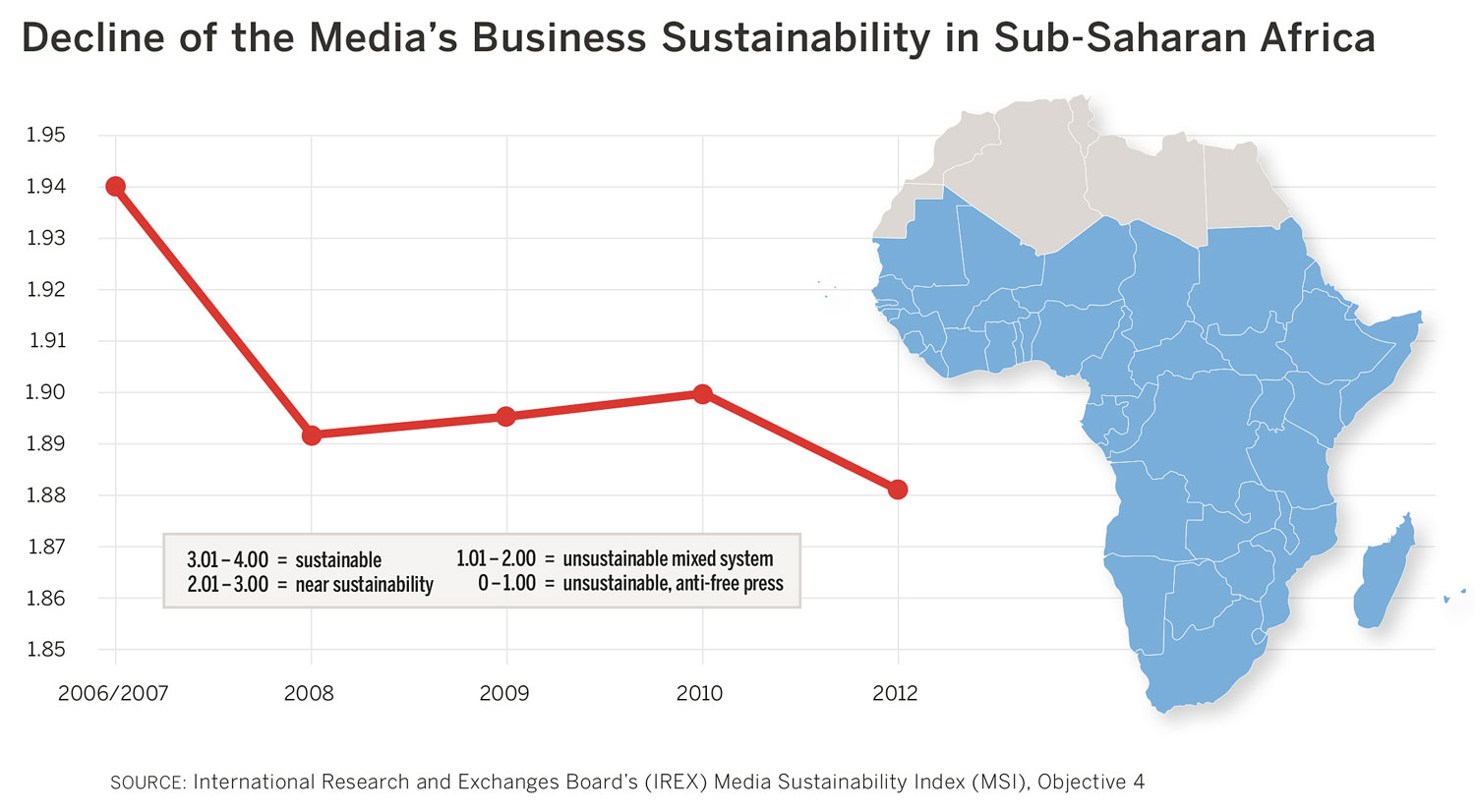

The Media Sustainability Index (MSI) conducted by the nongovernmental organization (NGO) IREX provides some of the most reliable indicators of the financial health of journalism in a given region. Last published for sub-Saharan Africa in 2010, the index found that in sub-Saharan Africa

financing and media management is the weak link, threatening sustainability and independence. With four years of tracking the business side of media health as well as the political and professional features, it is clear that business management and sources of funding for the media, measured by Objective 4 in the MSI, is the missing foundation for many other aspects of media health…8

While many media outlets do struggle in sub-Saharan Africa, a few major media houses prosper within oligopolies that span print, radio, and television markets—and these large players have been the prime target of capture by political actors. In Cameroon, for instance, the major media houses have long been polarized between warring political factions;9 in Kenya, the three major media holding companies are all aligned, directly or indirectly, with major political dynasties.10 In South Africa, the proximity of the Independent Media Group’s chairman, Iqbal Survé, to the ruling African National Congress (ANC) has led to accusations of biased reporting, while the controversial Gupta family,11 said to have “captured” the country’s president, Jacob Zuma, recently sold their pro-government newspaper The New Age and TV channel ANN7 to Zuma supporter Mzwanele Manyi. In the countries where the media have become aligned with political actors, journalists often focus on political issues or actions of the government, leading to a narrow, elite narrative that marginalizes parts of the population. Even independent, commercial media can focus so much on the interests of wealthy audiences that they neglect issues of interest to the majority of citizens.

Unfulfilled hope for digital media in sub-Saharan Africa

Meanwhile, the early hope that digital communication would disrupt the political polarization of media in sub-Saharan Africa has slowly given way to concern about new threats to pluralism in the digital media environment.

Kenya, a country with one of the continent’s most vibrant media systems, highlights the growing concerns over digital technology. In the 2007 elections, SMS (short message service) technology on feature phones provided a platform for the spread of rumors and misinformation that may have contributed to the post-electoral violence.12 Ten years later, online “fake news” (which still remains a fuzzy and at times counterproductive label13) has been highlighted as a concern: in the first-ever national survey conducted in Kenya on the topic, 90 percent of the 2,000 respondents reported having seen false or deliberately misleading news pertaining to the 2017 elections.14

Digital media have also not proven to be as resilient to the influence of elites in sub-Saharan Africa as was previously hoped. South Africa’s Gupta family maintains a close relationship to President Jacob Zuma and, until recently, controlled a 24-hour TV station and daily newspaper, among other assets. The family’s influence on digital media has recently been highlighted by journalistic investigations alleging that the family had financed an online propaganda campaign intended to counter the growing unease about its influence over the government.15 And governments in the region, too, have increasingly impinged on internet freedom. Cameroon and Ethiopia, for instance, have shown themselves willing and able to shut down the internet or block targeted content in ways that were not deemed a threat just a few years ago.16

In this environment, media pluralism still remains an elusive ideal in sub-Saharan Africa. While democratic gains have been made in some countries on the continent, media organizations, journalists, and bloggers remain under pressure in many places. Despite laws guaranteeing freedom of the media in principle, in practice media producers in many African countries are still hampered in their work because of internet censorship, threats to and attacks on journalists, censorship of the media or lack of understanding of media laws, and media owners that put commercial or personal interests above the public interest.

The result of the above pressures is a breakdown of ethical values and standards, creating a vicious circle wherein erosion of trust in the media may lead to less public support for journalism and consequent attempts by the media to gain audience interest by resorting to ever more sensationalist coverage. This vicious circle continues to have a spiral of consequences when the low quality of journalism makes it increasingly difficult for proponents of media freedom to garner support from democracy activists and the public at large for press-friendly reforms.

The ebbs and flows of media freedom and democracy, as seen from South Africa

In South Africa, the post-apartheid constitution adopted in 1996 has widely been lauded for enshrining freedom of expression, including freedom of the press. After the draconian laws restricting reporting under apartheid were repealed, the democratic era brought much greater freedom to the media, which are now self-regulated through a Press Council and an Independent Communications Authority, including a Broadcasting Complaints Commission. These bodies have allowed for citizens to have much greater say into what constitutes ethical reporting, and to act as watchdogs over the independence, truthfulness, and balance of the South African media.

Thousands of people march to Parliament in Cape Town, South Africa, to demand that the President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, step down immediately because of corruption in his government. April 2017.

In the more than two decades since the country became a democracy, the South African press has made use of these freedoms to deepen democracy, especially by playing a robust role in rooting out corruption and holding politicians accountable. However, the relationship between the media and the ANC government has grown increasingly tense. As criticism of the ANC government’s corruption and reports of “state capture” has been growing, so have threats to press freedom. The proposed Protection of State Information Bill (dubbed the Secrecy Bill) would regulate state information in a way that would impede the media’s and whistleblowers’ ability to uncover corruption. The ruling party has also proposed a Media Appeals Tribunal that would replace the self-regulatory process and have statutory powers to impose penalties on journalists.

In the wake of allegations of an improper relationship between South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma and the wealthy Gupta family that would amount to “state capture,” hundreds of fake Twitter accounts circulated false or misleading information to deflect criticism away from the president. With the help of a British public relations company, Bell Pottinger, a narrative of “white monopoly capital” was created to cast aspersion on journalists and discredit critics of President Zuma.

Although these various attempts to hamper the hard-won gains of media freedom since the attainment of South African democracy have been met with vigorous resistance from civil society groups and the public, they provide an illustration of the kind of decline in media freedom—after initial democratic progress—that can also be seen in other African countries since the 1990s.

The place of media in African politics

Participants in the July 2017 consultation in Durban discussed how to get media back on the political agenda. Where have media issues been prioritized? Where have media issues been ignored? Looking back historically at the place of the media as a subject of political discussion offers a crucial insight in how future advocacy coalitions can succeed: where broad coalitions can mobilize around core values and strategic targets, media pluralism can be made a political priority.

Participants in the July 2017 consultation in Durban discussed how to get media back on the political agenda. Where have media issues been prioritized? Where have media issues been ignored? Looking back historically at the place of the media as a subject of political discussion offers a crucial insight in how future advocacy coalitions can succeed: where broad coalitions can mobilize around core values and strategic targets, media pluralism can be made a political priority.

As described above, African media organizations were a product of colonialism and historically caught up in struggles for independence and freedom from colonial rule, in contestations over their relationship to post-colonial governments and in economic and political developments and upheavals.17 Central to these contestations were questions of press freedom, independence, and plurality of the media. These values have often been undermined in the post-colonial era as a result of political and socioeconomic reversals that took place in many newly independent African states.18 One-party post-colonial states did not allow for critical voices, and as a result media outlets were (and continue to be in many African countries) harassed or pressured into silence, and media pluralism was discouraged in favor of state control of the media.19 Economic crises further eroded the gains made to establish independent media outlets because of a lack of resources and African states’ reliance on foreign capital. Demands for greater media freedom, independence, and diversity have, however, also routinely formed part of the conditions for foreign aid, and have been included on the agenda of democratizing social movements from within the continent.20

Media organizations in African countries today are also increasingly influenced by developments occurring elsewhere in the world. New geopolitical shifts, like the entry of Chinese media into the continent as part of that country’s “soft power” efforts,21 continue to raise new questions about the role, responsibilities, and potential for the continent’s media to contribute to democratic culture. The rapid development of technology is altering media routines and practices (especially the shift from print and broadcast media to digital and mobile); the media’s business model is in limbo as advertising revenues dwindle; and, on the political front, an authoritarian revival is notable not only in Africa but also in the Global North, with implications for the defense of media freedoms.

The media remain high on the political agenda in many African countries where there is contestation over the value of democracy, governance, and the public interest. In some African countries, however, the media are low on the political agenda precisely because they are suppressed, or because the media’s democratic role is not open for discussion. In countries where journalism is a regular topic for discussion, various issues are typically salient. Among these are:

The media remain high on the political agenda in many African countries where there is contestation over the value of democracy, governance, and the public interest. In some African countries, however, the media are low on the political agenda precisely because they are suppressed, or because the media’s democratic role is not open for discussion. In countries where journalism is a regular topic for discussion, various issues are typically salient. Among these are:

- REGULATORY CONCERNS, including decriminalization of libel and defamation (e.g., in Mali where a new bill on depenalization is currently discussed), censorship, and statutory regulation for the media

- CODES OF ETHICS, which may include specific references to emerging issues such as cybercrime and internet regulation (currently under discussion in Namibia as well as in Senegal, Nigeria, and Niger where regulation is done through the press code), protection for whistleblowers, and corruption

- THREATS TO JOURNALISTS (e.g., the recent interdict obtained by the South African National Editors’ Forum against the organization Black First Land First to prevent them from threatening and intimidating journalists, and the attacks on journalists in Somalia, which have attracted much international attention but have been framed as the killing of “militants” in the country itself, where there is a low focus on media in political debates)

- REPRESSION OF THE MEDIA under the guise of anti-terrorism laws (e.g., in Senegal where the press code and the penal codes have been amended)

- COMMERCIAL COMPETITION, CONCENTRATION, AND CONGLOMERATION (e.g., in Kenya where there is fierce competition between media houses to attract government business) and their impact on editorial independence. Government ownership of media remains a controversial issue (e.g., in Uganda where a high proportion of media is owned by government), as well as journalists’ salaries and payment (which, if not consistent or sustainable, may open journalists to external influences and pressures that compromise their independence)

- MEDIA’S ROLE IN ELECTIONS, where the media often become a platform where political battles are fought

In all the above issues, the public’s trust in the media is of crucial importance to ensure that the media can play a constructive role in democratic debate and contribute to sustainable development. When partisanship sinks in, it becomes hard to argue for the importance of journalists as democratic stakeholders who deserve safeguards. For civil society and regulatory bodies to contribute to an enabling environment for the media, there must be a foundation of public support for the media as a democratic institution.

The interlinking values of pluralism, quality and ethical journalism, and freedom of expression have therefore been at the center of historical and contemporary debates around the role of the media in promoting and deepening democracy on the African continent. These three values can be seen as intertwined in the landmark Windhoek Declaration in 1991. This declaration by African journalists was a pivotal moment in the promotion of media freedom on the continent. The declaration opens with a call for “the establishment, maintenance and fostering of an independent, pluralistic and free press” which is seen as “consistent with article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” and “essential to the development and maintenance of democracy in a nation, and for economic development.”22

Mercy Alomba in 2013 at the controls at Pamoja FM, a community radio station serving the Kibera neighborhood in Nairobi.

Considering the important role that a free and pluralistic media can play in deepening democracy and reversing some of the backsliding towards greater authoritarianism that has taken place in various African countries since the 1990s, it is important that democratic activists pay attention to this broader enabling environment for media pluralism. And media advocacy should not rest on its mere instrumental or economic value—i.e., a more commercially successful media—but on its inherent democratic good, namely the assumption that a greater diversity of voices and perspectives, drawn from as wide as possible a range of citizens in a country, is important for the well-being of democratic culture, tolerance, and peace.

The work that is already being done across various African countries to contribute to such a diversity of voices—through a range of NGOs and civil society organizations that advocate for greater inclusion of marginalized voices, whether these are identified in terms of gender, ethnicity, or communities of interest, and those who advocate for the media’s own position in society and work to safeguard their independence and viability—could benefit from greater cohesion and collaboration. It is for this reason that participants in the consultation proposed building broader coalitions across the continent to ensure that space and resources are provided that would allow for greater pluralism of media across the continent.

Building broader coalitions for media reform

The group of experts agreed that a multistakeholder network of non-state actors working with governments, parliamentarians, regional and international bodies, regulators, and others could play an important role in supporting a conducive legal, regulatory, and economic environment for media and in defending independent voices, especially when under attack. The network could serve as an essential resource for confronting a complex combination of global and regional challenges to media systems that threaten to reverse the progress made on the continent in fostering pluralism, quality journalism, and freedom of expression.

The group of experts agreed that a multistakeholder network of non-state actors working with governments, parliamentarians, regional and international bodies, regulators, and others could play an important role in supporting a conducive legal, regulatory, and economic environment for media and in defending independent voices, especially when under attack. The network could serve as an essential resource for confronting a complex combination of global and regional challenges to media systems that threaten to reverse the progress made on the continent in fostering pluralism, quality journalism, and freedom of expression.

The network would focus on building broad coalitions, including media associations, human rights groups, media outlets, legal and judicial organizations, and trade unions to work on four areas of objectives:

- Solidarity among proponents of vibrant media systems

- Sustainability of media outlets and markets

- An African voice in digital debates

- Media literacy and professionalism

Each of these themes was elaborated upon by representatives from different regions on the continent by considering key challenges and highlighting success stories.

KEY OBJECTIVES FOR THE NETWORK

Solidarity among proponents of vibrant media systems

When media are under attack or freedoms are threatened by repressive laws, defenders of independent media in sub-Saharan Africa should be able to activate networks that extend beyond the usual media stakeholders to include human rights groups, law societies, faith-based organizations, and private-sector bodies that can provide a coordinated and multifaceted response at local, regional, and continental levels. This network will uphold central media values and emphasize the importance of media as a resource for citizens. The solidarity network could be built upon existing networks, but may require “honest brokers” (participants cited UNESCO as a possible honest broker) to establish trust between them and facilitate agreement. Media organizations should foster solidarity amongst themselves, but also build reciprocal coalitions with various other groups such as the judiciary and civil society. For the network to succeed, media outlets and freedom of expression defenders must provide support to civil society organizations and legal practitioners confronting the threat of shrinking civic space on the continent.

A regional network could build solidarity among African journalists by advocating against violence against journalists perpetrated by both state and non-state actors. A taxonomy of violence could be mapped to see the history of this violence and how it is meted out against journalists working on different kinds of stories, in order to develop a risk assessment mechanism for journalists. When journalists are attacked or killed, the network could push for an investigation and keep the issue on the public agenda.

The network could be strengthened by bringing in representatives from civil society, faith-based organizations, human rights organizations, researchers and trainers, and others. To build on existing networks of African journalists, co-conveners from across the region could be appointed. For instance, in Western Africa, the Media Foundation for West Africa could be approached, in South Africa, the South African National Editors’ Forum, and in East Africa, Article 19. Credible media associations and law societies could also be involved.

Sustainability of media outlets and markets

Tidiani Togola, director of the Democracy

Tech Squad, and Patience Zirima, director

of the Media Monitoring Project Zimbabwe

(MMPZ), speak on a panel in Durban,

July 2017.

Participants identified the financial sustainability and independence of media as the greatest challenges, with global trends related to the collapse of traditional journalistic business models being aggravated in the region by weak advertising markets and political elites’ undue influence on media outlets. In this environment, small and medium-sized news outlets and digital news startups are particularly vulnerable without support to level the playing field. The result of these commercial pressures is to leave media institutions, especially smaller community media organizations, exposed to undue political and economic influences that limit their capacity to work independently and in the public interest.

Examples abound of how African media outlets with failing business models are left vulnerable to problematic political and outside economic influences. Participants cited a few: in Nigeria, media organizations are primarily seen as businesses that have to make money at all costs. When media owners cannot keep their businesses afloat, the government may step in and take control, as was the case with the Daily Times newspaper in the 1970s, with the result that the paper was less able to criticize the government. Participants from Sudan remarked on how some newspapers in that country were owned by lawyers under the influence of security services, which limited the ability of journalists to practice independent journalism. In Kenya, fierce competition among media outlets, compounded by concentration of ownership, encourages outlets to curry government favor to win lucrative advertising contracts, which compromise journalists’ lack of independence. Mergers and acquisitions of media outlets limit the plurality of perspectives or render previously active outlets dormant. It was noted, for instance, that Cameroon nominally has around 900 newspapers but only 10 of them publish weekly, and many radio stations are no longer operational.

On the other hand, when government officials own media organizations, political players are able to shape public opinion and suppress dissent. Good management practices—such as ensuring managers and advertising staff cannot interfere in the editorial content—remain an ideal that many African media outlets should still be striving towards.

Paying journalists low salaries can also pave the way for undue political or economic influence. The changing nature of news production and consumption has put further pressure on the sustainability of independent journalism in Africa. While dwindling resources have resulted in shrinking newsrooms and diminished journalists’ ability to do investigative work, young African populations do not always prefer traditional media channels.

At the same time, large proportions of African societies still rely on traditional media to provide trustworthy news and accurate information. A regional network of African journalists could also help address some of these economic challenges, for instance by facilitating agreements to share printing presses between media outlets, or setting up multimedia platforms to syndicate news and make it more accessible to African citizens. A network may also be useful for helping smaller media businesses access capital, which has tended to be a problem across the region as banks often view making loans to media businesses as too risky. Members of the network could enter into joint ownership ventures, spreading the risk and allowing more players to enter the market.

Smaller news producers could benefit from forms of cooperation that could include sharing distribution networks, printing facilities, or access to advertising markets. The participants’ proposed network could also work to bring attention to reforms needed to loosen media ownership concentration and diminish the influence of political elites over major media outlets and the media regulators that frequently favor large news producers at the expense of smaller ones.

An African voice in digital debates

As has been the case in newsrooms globally, digitization has significantly impacted journalistic practices in Africa. The traditional advertiser-based business models are under severe pressure as audiences are increasingly deserting legacy media in favor of online media. The rise of social media, especially, has changed media consumption patterns, notably among the youth. The ease with which media can be produced online has made it possible for rumors, untruths, and disinformation to spread and threaten the credibility of the news media. At the same time, the speed and reach of digital media—including mobile media— have enabled African journalists to access information from sources anywhere in the world quickly and easily, and to disseminate information to a much wider audience than before.

In addition to its impacts on advertising revenue, the transition to a digital arena has brought other serious challenges. These include:

- Internet censorship and the stifling of free speech online, spanning a variety of forms that include blackouts, targeted blocking of websites, online forms of harassment, and legal threats or attacks aimed at suppressing dissenting voices online. Constitutional reform is needed to acknowledge access to the internet as a basic human right.

- Inequalities in internet access, which impede the ability of journalists to disseminate information and analysis via new media platforms to all sections of society. In some African countries, like Ghana with its #KeepItOn campaign, civil society has made attempts to fight internet censorship and broaden access.

- The dominance of major platforms like Facebook and Google can drown out local voices and independent African journalism. Participants identified the need for media organizations to develop relationships with these major providers that could be mutually beneficial.

- The spread of deliberately misleading information in Africa has necessitated building fact-checking mechanisms suited to the local contexts, and the development of media literacy programs to equip citizens with the skills and knowledge to identify trustworthy sources.

- The importance of placing the citizen at the center of discussions of new media platforms. Too often information and communication technology (ICT) policy in Africa is driven by business models at the expense of citizens. Another challenge is that multiple regulations in the ICT sector often impede freedom of expression. The heavy involvement of the security sector in ICT policy is another issue.

In light of concerns about unequal access as well as control over new media technologies, it is important to also recognize mobile phones’ significant potential in the African context, where penetration has been phenomenal. Mobile telephones can enhance traditional media— handsets can become a radio set for people who cannot read, and provide them with access to the media.

Amid growing online censorship by governments, including through the use of internet shutdowns, the network could strengthen advocacy efforts to make access to the internet a right and to establish ICT and internet policies that serve the public interest in the region. This advocacy work could build on the type of mobilization that has already been shown to be successful in putting pressure on governments—for instance, in Ghana during the previous election. When the government threatened to ban Twitter and Facebook on election day, the Economic Community of West African States, as part of its pre-election assessment, immediately called upon all media and social media actors to insist that banning social media during the election would infringe on the public’s right to information. As a result of this pressure, the government withdrew the threat.

Amid growing online censorship by governments, including through the use of internet shutdowns, the network could strengthen advocacy efforts to make access to the internet a right and to establish ICT and internet policies that serve the public interest in the region. This advocacy work could build on the type of mobilization that has already been shown to be successful in putting pressure on governments—for instance, in Ghana during the previous election. When the government threatened to ban Twitter and Facebook on election day, the Economic Community of West African States, as part of its pre-election assessment, immediately called upon all media and social media actors to insist that banning social media during the election would infringe on the public’s right to information. As a result of this pressure, the government withdrew the threat.

This type of advocacy for constitutional reform could take place on a national basis, as well as regionally through increased participation by regional stakeholders in international conventions and agreements. It is, however, important to consider the specific area of competency of each of these actors. Advocacy groups should involve governments in their attempts to address some of these challenges facing media practitioners. If governments are left out of discussions, it could create a polarizing “me against you” atmosphere that would exacerbate the antagonistic attitudes that many African governments already have against the media. It is, therefore, important to foster dialogue—if necessary, with the help of a broker like UNESCO—to influence government policy.

In this way, African governments, civil society actors, and the global internet governance community should formally work together to improve internet access in Africa, entrenching internet freedoms as fundamental principles in African constitutions. Furthermore, the network could help build the capacity of media stakeholders to engage with digital platforms such as Google and Facebook. The network could facilitate data collection on digital news consumption and digital advertising in the region and build the capacity of media representatives in the region to negotiate with these platforms on ways to bolster traffic and revenue to ethical sources of news and information.

Media literacy and professionalism

Participants envisioned how support for media literacy and journalistic professionalism might be integrated into national strategies for sustainable development entrenched in a democratic culture. For this vision to materialize, an informed, engaged, and active citizenry is needed. And to sustain such civic ideals, it is vital that the media act ethically. Aside from specialized training for journalists, standardsetting processes by the media sector itself are important, as well as independent regulators who are strong enough to hold the media accountable. If the regulatory system functions well, civil society organizations, the public, or governments can make complaints to regulators when they feel aggrieved by journalists and bloggers, rather than threatening, attacking, or incarcerating them.

Participants envisioned how support for media literacy and journalistic professionalism might be integrated into national strategies for sustainable development entrenched in a democratic culture. For this vision to materialize, an informed, engaged, and active citizenry is needed. And to sustain such civic ideals, it is vital that the media act ethically. Aside from specialized training for journalists, standardsetting processes by the media sector itself are important, as well as independent regulators who are strong enough to hold the media accountable. If the regulatory system functions well, civil society organizations, the public, or governments can make complaints to regulators when they feel aggrieved by journalists and bloggers, rather than threatening, attacking, or incarcerating them.

A hallmark of journalistic professionalism is the existence and respect for codes of ethics and self-regulatory or co-regulatory ethical frameworks. Different models of regulation exist across the continent and either contribute to journalism’s public integrity and credibility or constrain its independence. Where regulation works well, journalists will be able to co-regulate with citizen representatives such as in the case of South Africa. In this way, regulatory frameworks can not only support journalism and provide a defense against political interference, but also help journalists stay connected with citizens rather than operate in isolation, ensuring greater accountability of journalists to the public. An example in the South African context has been the interventions at the public broadcaster, the SABC, where civil society organizations such as the Save Our SABC Coalition have stepped in when the independence of journalists has been threatened, to insist on professional and independent journalism in the public interest. The Press Council in South Africa has also been revamped in recent years, by reassessing the press code and allowing for greater involvement by public representatives in the regulatory process.

In Namibia, civil society advocates have been effectively involved in shaping the regulatory framework and processes, and the government has accepted the current regulatory system. A code of ethics have been revisited and revamped, and civil society and media organizations have made contributions on issues such as cybercrime, whistle-blowing, and anti-corruption strategies. There has also been a great deal of public support that has helped drive advocacy for media independence.

In other parts of Africa there is much less recognition of journalistic professionalism or protection for journalists through regulatory or legal frameworks. In Africa, journalists are most often killed in Somalia, where the murders are often framed as attacks on “militants.” In many countries in West Africa, the repression of journalists is framed in the context of anti-terrorism laws (for instance, in Senegal, where amendments to the press code were mitigated by amendments to the penal code). In several of these countries, journalists themselves do not respect weak self-regulatory bodies.

Professionalism can, however, also become a smoke screen to protect narrow elite interests if journalists neglect to foster links with communities. It can also become a way for governments to stifle criticism by dismissing journalists as “unprofessional” if they disagree with them. This, participants reported, often happens in Central Africa.

Public support is crucial in establishing and maintaining journalistic professionalism and integrity in the face of political onslaughts. When independence gives way to partisanship, public trust in the media is eroded, making it difficult to argue that journalists are democratic stakeholders with professional rights and liberties. When the public views journalism as a luxurious exercise and not a top priority, journalists struggle to hold political power accountable, as has been the case in Zimbabwe.

Backed by evidence on the role of media in producing an informed and engaged citizenry with developmental outcomes, the network could marshal higher levels of political support and new resources for media literacy and journalistic professionalism. Universities, ministries of information and communication, statutory and self-regulatory bodies, media houses, and others need to work together to develop more integrated and comprehensive approaches to this challenge, with support from international partners including UNESCO. Included in the approach of such a network would be an active engagement with African communities with the goal of listening to the information needs and expectations of citizens and re-establishing relationships of trust between media and their users. The network would aim to create the space needed to develop more ambitious and forward-looking strategies.

An assessment of current networks

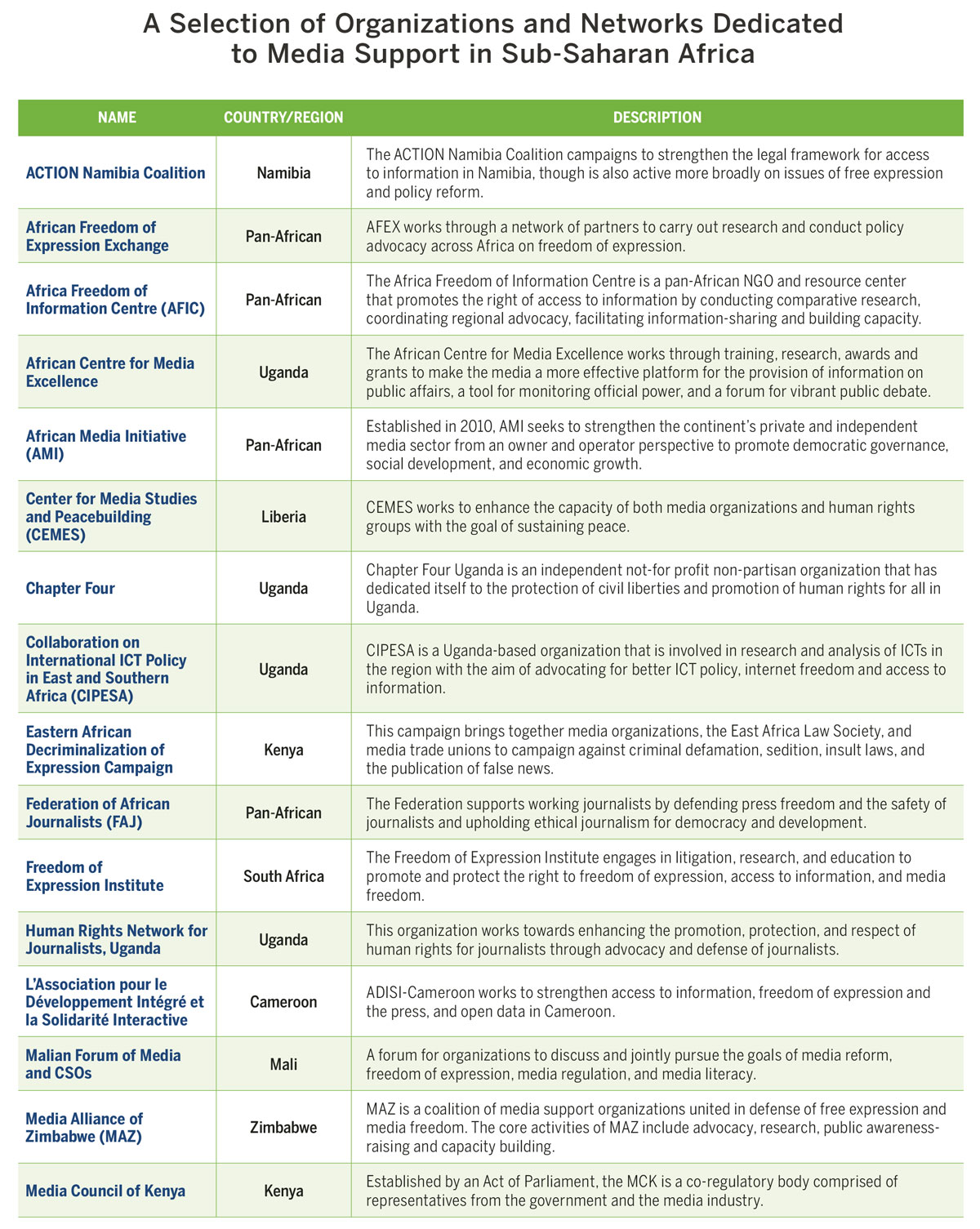

The consultation participants agreed that a significant capacity already exists on the continent to help shape media systems in the current period of transition in a way that favors democratization, and they helped identify the key organizations, campaigns, and networks that could contribute to the goals outlined above.

The list of organizations, included in a table on page 21, is by no means comprehensive, and is certainly biased towards the countries represented by the participants, but it is arguably representative of the kinds of actors and networks working on media issues at present, their approaches and strategies, and their priorities. In that respect, it provides an opportunity to assess the capacity available for achieving the goals outlined above, and the areas where new capacities or networks would be required. Four major issues emerge from a brief analysis of these aspects of the list:

- ACTORS: A range of media-related organizations are active in the region. These include government actors who co-regulate with media industry representatives (in the case of the Media Council of Kenya), trade unions (the National Union of Cameroonian Journalists), researchers (the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa), and media owners and operators (the African Media Initiative). In some cases, national organizations already consist of a coalition of groups, such as the Right to Information Coalition in Ghana and the Action Namibia coalition, which campaigns for legal protections for access to information. Networks of journalists and media freedom campaigners also exist on a national and regional level, e.g., the Media Alliance of Zimbabwe, the Media Institute of Southern Africa, the Partnership for Media and Democracy West Africa, and the Federation of African Journalists.

- TOPICS: Most of the organizations doing advocacy work on the list are focused on winning gains in the frameworks governing freedom of expression, access to information, and the protection of journalists, or on reversing draconian laws used to jail or intimidate journalists. But many of the major challenges identified by the participants and highlighted above—several emanating from the sustainability of the sector and its ability to maintain economic independence from political manipulation—are not well represented. Given the problems identified that relate to commercial pressures on journalism and the lack of resources in the sector, there seems to be a need for more representation of media owners and networks that can help independent journalists find sources of funding for their work or media outlets. Organizations aimed specifically at supporting development in the African digital arena, as well as those that promote media literacy and education, are also under-represented compared with advocacy groups.

- NETWORKS: Some countries have thicker “clusters” than others and there are a few cross-border networks working in subregions, though they could no doubt be stronger. There are virtually no networks that bring together actors from across the whole region. The networks that do exist, at least based on the examples identified in this mapping, are poorly organized for negotiating with global corporate giants or participating in internet governance forums. In order for African voices to be heard more clearly in global digital debates, for instance, stronger organizations, which could lobby or advocate on behalf of African media organizations in these international forums, need to be established.

- APPROACHES: With the exception of research done by organizations aimed at specific goals such as freedom of expression (e.g., the Freedom of Expression Institute in South Africa) or policy interventions (e.g., Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa), specialized and broad-ranging research capacity does not exist within existing networks, and there is almost no capacity for monitoring and gathering data comparatively across countries. This is a weakness that should be addressed when a broader coalition is formed in the region, as advocacy, support, and solidarity networks will be more effective when underpinned by well-informed analyses. Collaboration between media organizations, journalists, policy think tanks, and universities in the region is therefore important for devising new approaches to policy-making and developing new skills for practitioners to meet the challenges of solidarity, sustainability, voice, and literacy as outlined above.

Recommendations and further steps

As pointed out at the start of this report, there is a close link between a sustainable, independent, and robust media and a vibrant democracy. Despite initial gains for both freedom of the media and democratic culture across Africa in the 1990s, recent years have seen the deterioration of democratic culture and a growing intolerance towards the media across the region.

In the regional consultation, several instances of this regression were noted, and a number of key challenges for the media identified. These challenges—building solidarity, ensuring sustainability, amplifying voice, and developing literacy—would require a sustained effort as well as innovative approaches that go beyond a mere increase in advocacy work. While advocacy for media freedom and independence remains the cornerstone for strengthening the media’s place in African democracies, this advocacy needs to take heed of the shifting terrain of media in the region as well as in a global context. This includes increased commercial pressure on legacy media as a result of a growing emphasis on and preference for digital information and communication technologies as well as the entry of new global players into the African media space.

In the regional consultation, several instances of this regression were noted, and a number of key challenges for the media identified. These challenges—building solidarity, ensuring sustainability, amplifying voice, and developing literacy—would require a sustained effort as well as innovative approaches that go beyond a mere increase in advocacy work. While advocacy for media freedom and independence remains the cornerstone for strengthening the media’s place in African democracies, this advocacy needs to take heed of the shifting terrain of media in the region as well as in a global context. This includes increased commercial pressure on legacy media as a result of a growing emphasis on and preference for digital information and communication technologies as well as the entry of new global players into the African media space.

To ensure that African media organizations remain viable players in this changing political and economic landscape, new coalitions need to be built and existing ones strengthened. The existing coalitions in the region display certain weaknesses: they tend to be unevenly spread across the region and they tend to focus on a narrow band of concerns. While the existing organizations do important work pertaining to legal protections, constitutional guarantees for freedom of expression, and the safety of journalists, they are weaker in the areas of digital access, infrastructure, and ICT policy. More capacity should be built to enable research into fast-evolving areas of the media such as digital, mobile, and social media, and the questions concerning freedom, independence, and sustainability that arise from this new and rapidly shifting arena.

Instead of merely adding more networks and linking existing ones together across the region in a show of solidarity, there is a need for strategic thought around the type of collaborations needed in the region. While collaborations between existing like-minded organizations should be supported, there is a growing need for media organizations to think strategically about working with research institutions, policy think tanks, and actors in the digital sphere that can contribute new skills and strengthen engagement with policy-makers and powerful global players, in the digital arena in particular. In other words, media reform in Africa should move beyond questions of freedom and independence in the political sphere, to finding new and innovative strategies for enhancing the media’s capabilities and invigorating citizen participation in the evolving digital landscape—with all the economic, political, and ethical questions that operating in this landscape brings. Two key imperatives in this regard stand out: the need to build new networks of solidarity and develop new skills and approaches.

- BUILDING NEW NETWORKS OF SOLIDARITY: Now that a mapping exercise has identified existing stakeholder networks, working groups should be formed among the participants to elaborate specific action plans and proposals. These working groups should collaborate to strengthen the network, share information across regions, and join forces to engage in advocacy. The participants identified the need to formulate a common position for advocating on media issues at the global level and at important upcoming events on the continent. In building these new networks of solidarity, particular attention should be paid to under-represented organizations and actors in existing coalitions, such as research groups, media literacy organizations, and transnational or regional networks.

- DEVELOPING NEW SKILLS AND APPROACHES: For African media to continue to be relevant in a political context of growing intolerance for the media, it needs to develop new strategies of coping with challenges to its democratic role. While many legacy media organizations in the region have remained captured by political and economic elites, the new and evolving social media arena can also serve to undermine informed, democratic debate through, for instance, the spread of disinformation, untruths, and threats. To meet these new challenges, more than advocacy for media independence, freedom, and pluralism will be required. Journalists and citizens in the region will have to develop critical literacies that would enable them to meet these new challenges and engage more effectively with policy makers and ensure greater sustainability for the media in a changing environment. Collaboration with research organizations and universities in the region can play an important role in this regard. A particular area of focus in research should be on questions of sustainability and independent sources of funding in the new digital environment.

Given the democratic regression experienced in the region in past decades, persisting obstacles to media freedom and independence, and emerging challenges in the shifting digital landscape, the media in Africa remain crucial for the deepening and broadening of democracy on the continent. The strategies suggested in this report are initial steps towards this ideal.

Footnotes

- The term the “third wave” was coined by Samuel Huntington; see The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991).

- Kwame Karikari, “African Media Breaks ‘Culture of Silence,’ African Renewal Online, August 2010, http://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/august2010/african-media-breaks-%E2%80%98culture-silence%E2%80%99-0.

- Kwame Karikari, “Press Freedom in Africa.” New Economy 11 (3): 184–86, 2004.

- Keyan Tomaselli, “Media Ownership and Democratization,” in Goran Hyden, Michael Leslie, and Folu Ogundimu, eds., Media and Democracy in Africa (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2002), 129–56.

- Larry Diamond, “Facing Up to the Democratic Recession,” Journal of Democracy 26 (1):141–155.

- There are 49 countries in sub-Saharan Africa in Freedom House’s dataset. South Sudan was added to the dataset in 2012 after its independence from Sudan, and Somaliland, though not formerly recognized as a country, was included in the dataset in 2015. This report also includes Sudan as a sub-Saharan country, though it is not always considered part of the region.

- Anya Shiffrin, ed., In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017).

- IREX, Media Sustainability Index 2010 (Washington, DC: IREX), https://www.irex.org/sites/default/files/pdf/media-sustainabilityindex-africa-2010-full.pdf.

- Francis Nyamnjoh, Africa’s Media, Democracy and the Politics of Belonging (London: Zed Books, 2005).

- Othieno Nyanjom, “Factually True, Legally Untrue: Political Media Ownership in Kenya,” (Nairobi: Internews, 2012).

- See Black Opinion, “Our Captured Media,” (July 17, 2016) https://blackopinion.co.za/2016/04/15/our-captured-media, and Stephen Grootes, “ANC to Investigate Zuma Relationship with the Guptas,” Eyewitness News (March 21, 2016) http://ewn.co.za/2016/03/21/ANC-to-investigate-Zuma-relationship-withthe-Gupta-family.

- Jamal Abdi Ismail and James Deane, “The Kenyan 2007 Elections and Their Aftermath: The Role of Media and Communication,” BBC World Service Trust Policy Briefing (1: 1–16, 2008).

- For a discussion of the various issues conflated by the term “fake news,” see Claire Wardle, “Fake News. It’s Complicated,” First Draft, February 16, 2017, https://firstdraftnews.com/fakenews-complicated/.

- GeoPoll and Portland Communications, “The Reality of Fake News in Kenya,” (Nairobi, 2017).

- “Gupta Fake News Empire,” Times Live, https://www.timeslive.co.za/group/Gupta_Fake_News_Empire/.

- Guy Berger, “World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: Regional Overview of Africa,” (Paris: UNESCO, 2014).

- Kwame Karikari, “African Media since Ghana’s Independence” in Elizabeth Barrett and Guy Berger, eds., 50 Years of Journalism: African Media Since Ghana’s Independence (Johannesburg, South Africa: The African Editors’ Forum, 2007), 10.

- Karikari, “African Media since Ghana’s Independence,” 16.

- Ibid.

- Karikari, “African Media since Ghana’s Independence,” 17.

- X. Zhang, H. Wasserman, and W. Mano, eds., China’s Media and Soft Power in Africa: Projection and Perceptions (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

- “Declaration of Windhoek on Promoting an Independent and Pluralistic African Press, Namibia, 1991,” via UNESCO.