Key Findings

The majority of people now live under illiberal regimes or some form of autocracy as a consequence of democratic declines occurring globally since 2010. Understanding the driving forces behind this historic setback to democratic progress will be essential for turning the tide. An analysis of media indicators in the Varieties of Democracy Institute’s global index illustrates a common pattern in countries experiencing democratic setbacks, with important implications for action. Time and again, would-be autocrats seek to methodically dismantle press freedom and independence as an early step towards consolidating power. Analysis of this trend bolsters a growing international effort to support and safeguard independent media as a strategy for revitalizing democratic progress.

– Attacks on independent media are warning signs of deepening autocratization. Early intervention to protect a free press is critical for preventing further erosion of the space for democratic dissent and free expression.

– The process of silencing independent journalism is often slow and gradual. This quiet erosion of media independence and pluralism allows autocrats to flood the information space with partisan, propagandistic media.

– Illiberal regimes learn from one another, using tactics and strategies to silence independent journalism that have proven successful in similar contexts.

Introduction

Scholars of history and politics are engaged in a profound debate over why democratic progress has recently slowed, or even reversed, in what has variously been described as decay, backsliding, deconsolidation, and recession.1 This pattern of democratic stagnation and decline remains inextricably linked to the simultaneous erosion of press freedom and independence witnessed over the past decade.

An in-depth analysis of several media-related indicators from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute dataset, conducted for this report, points to how independent media are often the first to be targeted by would-be autocrats. The findings suggest that the press is not only a “canary in the coal mine” when it comes to identifying early warning signs of democratic backsliding, but also a vital first line of defense against further assaults on democratic rights. Such findings bolster growing calls for a redoubling of support to independent media. The Global Campaign for Media Freedom, launched by the United Kingdom and Canada in 2019, has brought together civil society organizations and high-level government representatives, generating new pledges that have included the creation of the Global Media Defense Fund.2 The Forum on Information and Democracy recently issued a call to action for a “new deal for journalism,” urging governments and other influential stakeholders to take steps to improve funding and enabling environments for independent journalism.3

Yet much remains to be done. Support to bolster independent media is a small component of international efforts to promote democracy and good governance. Even as there is mounting evidence of the importance of independent journalism to democratic health, international efforts to protect it have not kept pace with the growing threats media are facing globally.4 Safeguarding a free and independent press is an under-resourced and poorly integrated part of global development assistance policies. While authoritarian leaders spend heavily and pay close attention to the media as a tool for their political and economic aims, democratic reformers and international donors have largely failed to make the news media a central focus of their efforts. Insufficient attention to independent media undermines broader efforts to help slow democratic backsliding and protect democracies under threat.

By drawing on analysis of media-related variables in 16 countries representing a variety of geographic, economic, and political contexts, a number of important patterns emerge. First, media are frequently a central focus of attack by leaders working to undermine democratic freedoms in their pursuit of control. In some cases, the space for independent voices is eroded as a prelude to the dismantling of other democratic institutions. In other cases, the news media experience a slow erosion of their ability to operate freely and independently through media capture or through increasing regulations, government fees, and official threats—death by a thousand cuts. The data also suggest that aspiring autocrats learn from one another and from more established autocracies, imitating the tactics that other governments have successfully used to stifle the press.

The story is one many know all too well. The past two decades in Russia provided a stark warning for democrats—and a potential playbook for autocrats—as President Vladimir Putin methodically worked to dismantle the space for a free and independent media. More recently, the Turkish crackdown on independent journalism gained global attention when President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan swiftly silenced voices of opposition around both the Gezi Park protests in 2013 and the attempted coup in 2016.5 As media crackdowns continue to spread across borders, the threat of democratic backsliding also grows. Eroding the ability of the media to operate independently and in the public interest paves the way for an autocratizing government to seize control. Declines in media freedom, pluralism, and independence are often part of larger efforts to silence public debate and dissent. Despite variations between countries and contexts, the dismantling of independent media systems as part of the autocratization process is remarkably similar. The sequences and paces may differ, but in every case examined as part of this study, autocrats have worked methodically to shrink the space for democratic media as they have consolidated power.

The story is one many know all too well. The past two decades in Russia provided a stark warning for democrats—and a potential playbook for autocrats—as President Vladimir Putin methodically worked to dismantle the space for a free and independent media. More recently, the Turkish crackdown on independent journalism gained global attention when President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan swiftly silenced voices of opposition around both the Gezi Park protests in 2013 and the attempted coup in 2016.5 As media crackdowns continue to spread across borders, the threat of democratic backsliding also grows. Eroding the ability of the media to operate independently and in the public interest paves the way for an autocratizing government to seize control. Declines in media freedom, pluralism, and independence are often part of larger efforts to silence public debate and dissent. Despite variations between countries and contexts, the dismantling of independent media systems as part of the autocratization process is remarkably similar. The sequences and paces may differ, but in every case examined as part of this study, autocrats have worked methodically to shrink the space for democratic media as they have consolidated power.

Crunching the Numbers

Measuring and analyzing how robust and free independent media are within a political and economic context is notoriously complicated. Numerous attempts have been made to systematically track and analyze media pluralism and ownership, media freedom, the safety of journalists, and more, at global, regional, and national levels.

While these initiatives provide critical insight, none are able to offer a complete picture of changes in the broader enabling environment for independent media over time. Frequently, data are not available for all countries or collected in a regular and systematic way. As a result, the data that are available are often not comparable from country to country, and fall short in terms of understanding shifts over time.

While these initiatives provide critical insight, none are able to offer a complete picture of changes in the broader enabling environment for independent media over time. Frequently, data are not available for all countries or collected in a regular and systematic way. As a result, the data that are available are often not comparable from country to country, and fall short in terms of understanding shifts over time.

The dataset produced by V-Dem is one of the most comprehensive attempts at a systematic understanding of independent media as part of broader democratic institutions and processes. V-Dem is the largest global dataset on democracy, an open access trove of nearly 450 indicators addressing electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian aspects of democracy. Drawing on more than 3,500 scholars and country experts worldwide, the dataset has produced over 30 million data points for 202 countries, spanning from 1789 to the present.6

Like other indices that attempt to measure press freedom and independence over time, the V-Dem dataset has drawbacks. Reporting can be inconsistent from country to country and year to year, and that inconsistency presents challenges in detailed modeling of specific indicators. Despite these limitations, examining media as part of the broader processes of autocratization provides a new lens for articulating the critical role of a free press to democratic governance, and how it features in the process of democratic decline. According to V-Dem’s 2021 democracy report, most of the indicators “substantially declining” in the past decade were ones related to freedom of expression and the media. In that same period, media-related indicators also accounted for a majority of the indicators declining in the greatest number of countries.7

This report draws from original quantitative analysis of 16 countries based on V-Dem’s 2020 dataset. Although V-Dem has since released its 2021 data, the trends identified and detailed below remain valid and are in fact increasingly evident on the ground. The data analysis tracked 15 indicators and indices over the past two decades. Most of the indicators examined were media-specific, while others, such as the Liberal Democracy Index, served as proxies addressing the political environment. See Appendix 1 for a full list of the key indicators addressed and their definitions, and Appendix 2 for a list of the countries analyzed.

For the data analysis, variables were first normalized between zero and one to facilitate comparability. In some cases, variables were also inverted for ease of visualization. For example, the V-Dem data show the government censorship of media value decreasing as censorship intensifies. Inverting the variable allows for a more intuitive visualization where the value increases as censorship increases.

Exploration of the data was broken into three phases: close descriptive analysis of the trends presented, structural break analysis to identify shifts and possible moments of transition, and time-series analysis to understand the relationship among variables over time. Time‑series analysis ultimately failed to prove useful given gaps in the data available over the 19 years analyzed. The findings and trends revealed through the data analysis were contextualized through desk research for the presented case studies. A close understanding of events in each country helped contextualize structural breaks identified in the data analysis by confirming the trends and transition periods that occurred in each country.

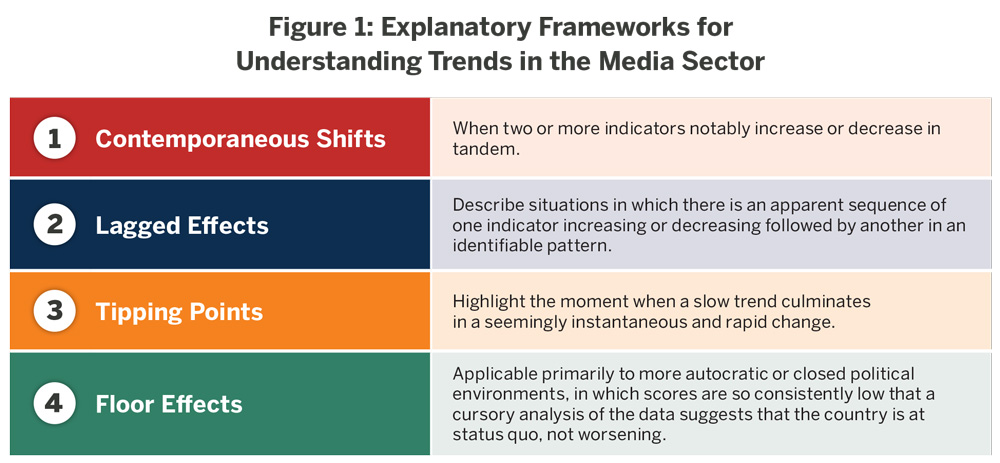

The interplay between independent media and other democratic institutions and processes is complex and varied. This complexity is reflected in V-Dem’s data. In the course of analyzing over a dozen V-Dem indicators on press freedom and the overall media environment, the following data-driven explanatory frameworks outlined in Figure 1 help make sense of the complexity and serve as ways to understand trends over time.8

Insight 1: Canary in the Coal Mine

On May 11, 2000—just four days after Vladimir Putin’s inauguration as president—masked federal agents raided the headquarters of what was then Russia’s largest private media company, Media-Most. Within a year, Media-Most and NTV, the country’s only major independent television network, were under the management of the state-controlled gas monopoly, Gazprom. In fact, all three federal television networks were under state control less than a year after Putin came to power. It would, however, take longer for the international community to recognize Russia’s stark turn away from democratic reforms.9

While Russia has become the most notorious perpetrator of media crackdowns in the process of autocratization, this data analysis confirms that autocrats often attack the media first. A weakened media system allows the government to limit critical, independent voices and disseminate its own messages. This enables it to dismantle other, more formal institutions of democracy, such as the judiciary and democratic elections, without the oversight and accountability that independent media provide.

There are several cases in the V-Dem dataset where a decline in free and fair elections follows several years after a substantial regression in indicators related to media freedom, freedom of expression, and media pluralism. In fact, free and fair elections by themselves are not the most effective way of monitoring the health of a democracy. Given that they typically occur once every two to four years, they make for an extraordinarily delayed warning flare if democracy is at risk. Given the sequencing of measures that autocrats typically use to cement power, indicators that measure the strength of the independent media environment offer a clear diagnostic check on the health of the democracy. The news media are the canary in the coal mine.

Even as Putin wasted no time in making an early example of Media‑Most,10 few expected the full extent of the crackdown and centralization of power that were to come,11 and which experts now recognize as the tell-tale signs of an autocrat’s tightening grip. At the time, indices like V-Dem’s Liberal Democracy Index could also have easily missed picking up on these important signs. Composite scores, while useful for understanding broad trends over time and across borders, inevitably miss incremental changes in the variables that comprise them. By the time the autocratic trend became undeniable a few years later, the Putin government had already dismantled the once-vibrant independent news media in Russia.

The case of Turkey highlights the potential of using indicators related to the media environment as a diagnostic check on democracy. Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) came to office in 2003. By 2005, the country’s score in V-Dem’s Freedom of Expression Index began to decline and media self-censorship was on the rise, even as Turkey aimed to promote its democratic values in a bid for European Union (EU) membership. Not until after 2006—a year in which V-Dem classified Turkey as an “undisputed electoral democracy”—would the country begin to decline in the Liberal Democracy Index.12

That deterioration remained gradual until two dramatic events precipitated crackdowns in Turkey: the Gezi Park protests in 2013 and the attempted coup in 2016. As Turkey’s democratic indicators took a sharp turn for the worse after 2012, V-Dem downgraded the country to an “electoral autocracy” in 2013.13 Both moments served as tipping points for Erdoğan’s crackdown on free expression, and scores of journalists were imprisoned under charges of terrorism or anti-state activity.14 By 2012, press freedom trackers like Reporters Without Borders had already dubbed Turkey “the world’s biggest prison for journalists,” and the country retained the title in 2013, 2016, 2017, and 2018.15 Freedom House similarly ranked the country “not free” beginning in 2013.16 Though many of Erdoğan’s first restrictions on the media environment were subtle, the early and continuing declines in media freedom were warning signals of broader democratic backsliding.

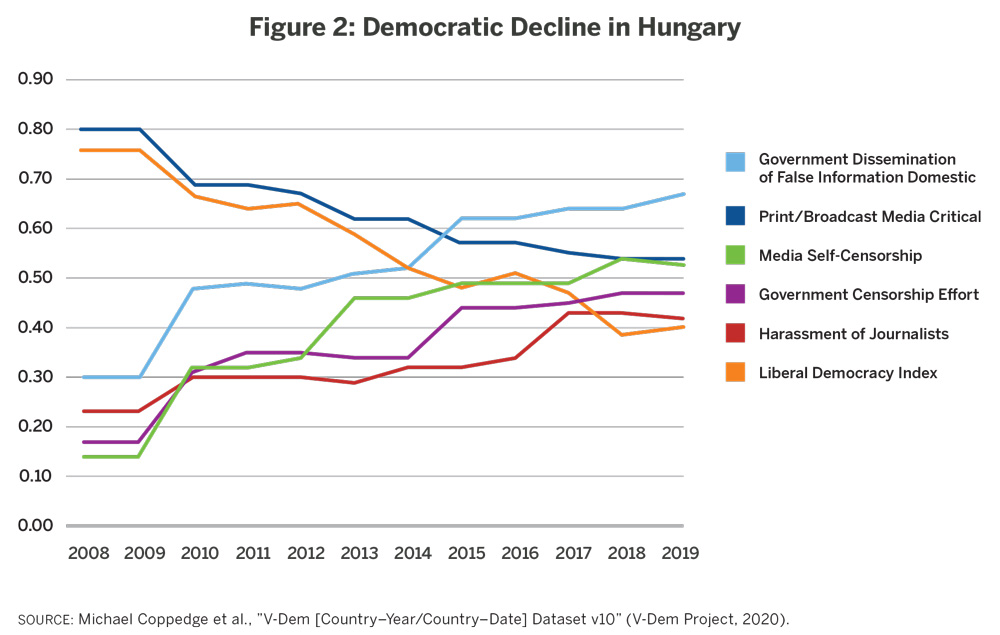

Often, a change in government or period of political transition marks the most notable shift in press freedom. In April 2010, Viktor Orbán was elected Hungarian prime minister when the nationalist Fidesz party swept back into power with a two-thirds parliamentary majority.17 Compared with the minimal shifts visible in Russia, Hungary’s democratic indicators underwent a swift and steady decline from 2010 onward. This deterioration was especially pronounced in the indicators tracking the health of Hungary’s media environment. As the space for critical and independent media shrank, censorship rose.18 The data show the rapid increase in attacks on the media from 2009 to the end of 2010, including increases in media self-censorship, government censorship of traditional media, and government dissemination of false information. Simultaneously, Hungary began its gradual but continuous fall in the Liberal Democracy Index.

Like Putin, Orbán began to dismantle press freedoms shortly after taking office. By December 2010, the Fidesz-led parliament had introduced and passed what many considered to be the most restrictive media law in the EU.19 Media would now be required to register with the state and produce only “balanced” news of “relevance to the citizens of Hungary.” Regulations would be enforced by a new state-appointed Media Council, which had the power to issue fines and suspend or close news outlets.20 Presciently, Hungarian writer and former dissident Gyorgy Konrad remarked at the time, “there is no calling this a democracy anymore.”21 It would take a decade of continued restrictions on the media, civil society, and public space before Hungary would lose its formal classification as a democracy, from both V-Dem and Freedom House.22

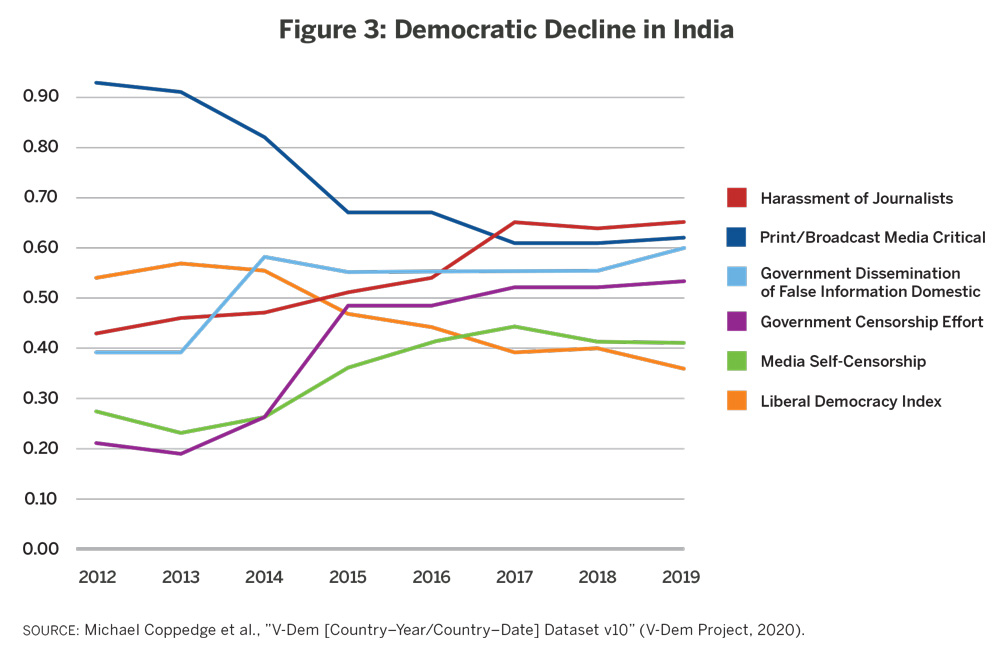

Halfway around the globe, in May 2014, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) swept to power. The following month, local outlet Scroll.in reported that the new prime minister had asked government officials to “refrain from speaking with journalists.”23 Instead, the BJP would cultivate its vast following through official channels, social media platforms like Twitter, and partisan chat groups on WhatsApp, while simultaneously delegitimizing and denying access to existing media outlets.24 The data show media indicators to once again be leading signs of a broader trend. By the end of 2014, the relevant indicators showed declines in media coverage critical of the government and increased self-censorship. Government censorship also worsened in 2014 and would deteriorate more rapidly the following year.25 This development is particularly stark given the proliferation of media outlets in India.26 Though the range of news media perspectives remains high, the amount of coverage critical of the government has dropped steadily since 2014.

For decades, India was celebrated as the world’s largest democracy. However, the BJP government, citing the ongoing threat of uprisings in Kashmir and various protests in recent years, gained notoriety for employing internet throttling and shutdowns more frequently than any other country.27 By 2021, V-Dem scores officially declared India an electoral autocracy,28 while Freedom House downgraded the country to “partly free,” citing media crackdowns as a leading cause.29

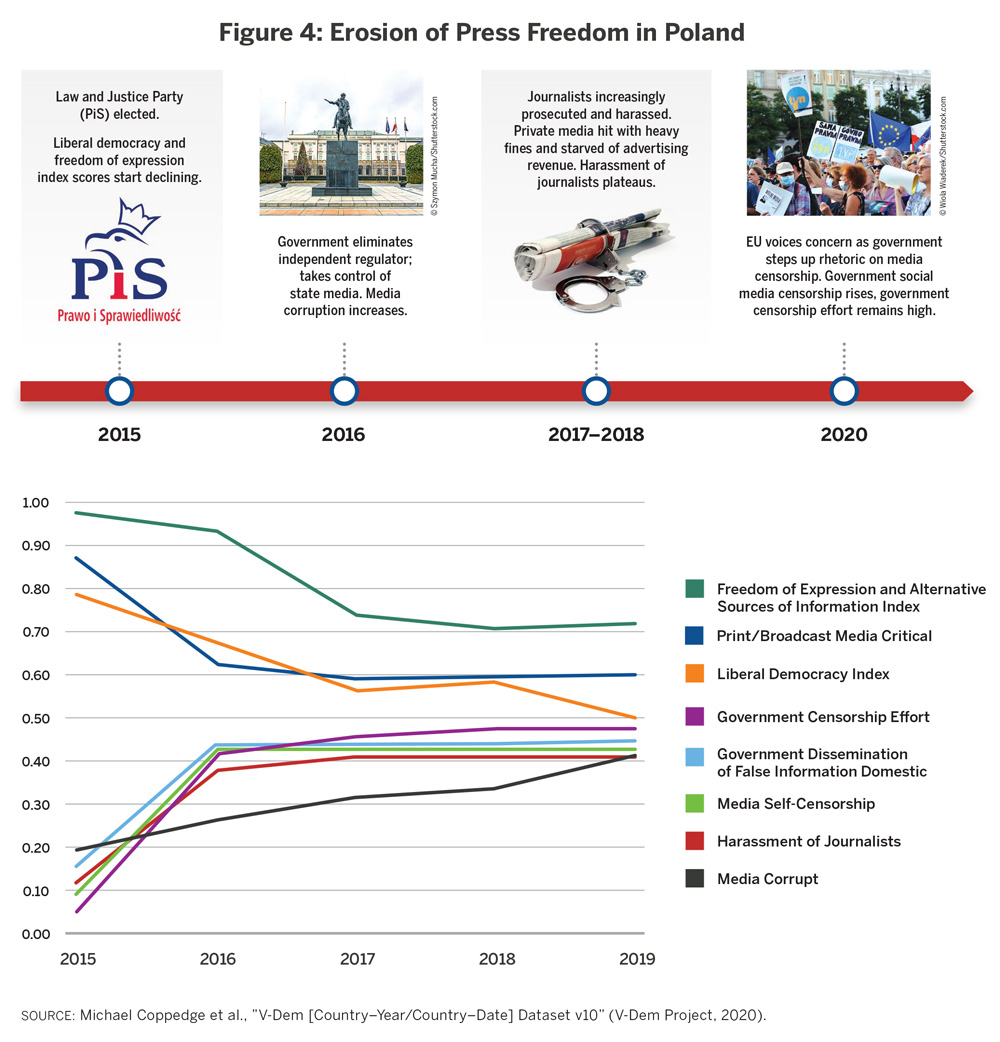

In other cases over the past decade, such as Poland and Egypt, media freedoms were not necessarily the first to drag down a country’s score on the Liberal Democracy Index, but they did appear to drop the most precipitously once the dominoes began to fall. Poland’s ultraconservative Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość; PiS) party, for instance, rose to power in 2015 and brought with it an immediate decline in the country’s democratic scoring. Some of the government’s first actions included curbing the independent judiciary.30 Lacking independent courts to turn to, news outlets were then left with little recourse in the face of growing accusations, regulations, and government collusion in the name of “repolonization,” which aims to limit foreign ownership and influence in the media.31

Even in such cases, when media freedoms are not the first to go, the deterioration of the enabling environment for independent media remains one of the loudest warning flares signaling that a democratic system is under threat. This is even more significant in cases of slow decline, like the “death by a thousand cuts” that independent journalists faced in Poland. The process of eroding media freedoms and undermining media independence is often so gradual as to be nearly negligible—and the canary is the miner’s best hope for recognizing the impending danger.

Insight 2: Slow Erosion of the Media Environment

“Will people go to the street about a media law? Maybe. They certainly won’t go to the street about a bunch of little administrative laws.” Wanda Rapaczynski, supervisory board member of Polish media outlet Agora, did not mince words as she discussed the threat facing independent media in Poland and the danger that comes with its slow erosion.32

Often, the process of silencing independent voices is a quiet and gradual one. Direct harassment of independent news outlets and critical journalists is by no means the only—or even the most efficient—method of silencing them. The gradual capture of the media environment by government-friendly owners, regulatory and administrative burdens, a biased judiciary, and shrinking financial incentives accomplishes the job more thoroughly. To a certain extent, these measures allow the government to avoid international condemnation and keep up a facade of democracy and free expression. Gradually, as genuine media independence and pluralism is eroded, autocrats flood the information space with partisan, propagandistic media.

Often, the process of silencing independent voices is a quiet and gradual one. Direct harassment of independent news outlets and critical journalists is by no means the only—or even the most efficient—method of silencing them. The gradual capture of the media environment by government-friendly owners, regulatory and administrative burdens, a biased judiciary, and shrinking financial incentives accomplishes the job more thoroughly. To a certain extent, these measures allow the government to avoid international condemnation and keep up a facade of democracy and free expression. Gradually, as genuine media independence and pluralism is eroded, autocrats flood the information space with partisan, propagandistic media.

In Poland, the PiS took a series of steps to attack the environment for independent journalism since it swept into power in October 2015. By January 2016, the new government had taken direct control of state radio and television, sidestepping the independent regulatory system that had been crafted when Poland ended one-party rule in 1989.33 As a result of this and additional threats levied at independent media in the country, several V-Dem indicators show rapid declines from 2015 to 2016: government censorship, media self-censorship, harassment of journalists, government dissemination of false information, media corruption through bribery, and critical media.

The government’s intimidation of independent media, ranging from direct harassment and prosecution of journalists to excessive fines for privately owned outlets, has continued in subsequent years.34 The government’s discourse on the repolonization of media in the country—which primarily targets private media with foreign support—continues to threaten independent voices even as the EU expresses concern about press freedom violations in the member state.35

This gradual process of restrictions and takeover is a well-documented and familiar trend, especially for countries trying to maintain some level of a democratic facade. In Russia, beginning in 2000 with Media-Most, media outlets and their parent companies were rounded up through a series of business takeovers, accusations of tax evasion, and any other charges that could be levied on those not toeing the government line. To many, some of those crackdowns may have even seemed valid, given Russia’s extensive corruption issues.36

The erosion of Hungary’s press freedom was also gradual, from the December 2010 media law cited above and continuing every year over the past decade. In that same 2010 media law, all state media and news production were placed under the politically appointed leaders of the Media Council, setting off a process of Fidesz-controlled state media and ad hoc regulations for those that were privately owned. The 2016 sale and shutdown of leading opposition paper Népszabadság highlighted one of many such moves to quietly close in on independent press.37 Two years later, in November 2018, media-owning oligarchs consolidated over 400 outlets into one pro-government foundation, the Central European Press and Media Foundation (Közép-Európai Sajtó és Média Alapítvány; KESMA).38 Like Poland, Hungary was expected to uphold the norms of press freedom outlined by the EU. However, administrative restrictions and the gradual consolidation and sale of news outlets offered a more subtle approach to controlling the information space.

A similar slow deterioration of the media environment can be seen in Turkey over the past decade. While public protests and journalist imprisonments grabbed global attention and seemed sudden, particularly in 2013 and 2016, the process was nonetheless a methodical one. As in Hungary, government-friendly businesses took control of outlets while editors and journalists were either in jail, in court, or facing a backlog of bureaucratic requirements.39 Their online counterparts simultaneously grew so accustomed to censorship that anything likely to be blocked was considered “VPN news.”40

Examples like Russia, Hungary, and Turkey make it relatively easy to track how the gradual erosion of news media independence and press freedoms occurred. Poland appears to be joining their ranks. The slow, multilayered, and methodical nature of attacks on independent journalism is why the erosion is so difficult to identify as it is happening. The effects are most clearly felt only later, once the damage to the media system is already severe. As a result, it is difficult to call the public to the streets in protest or look to the global community for support before it is too late. Understanding how this process unfolds is critical, especially given that media declines are frequently predictive of subsequent broader assaults on democratic institutions.

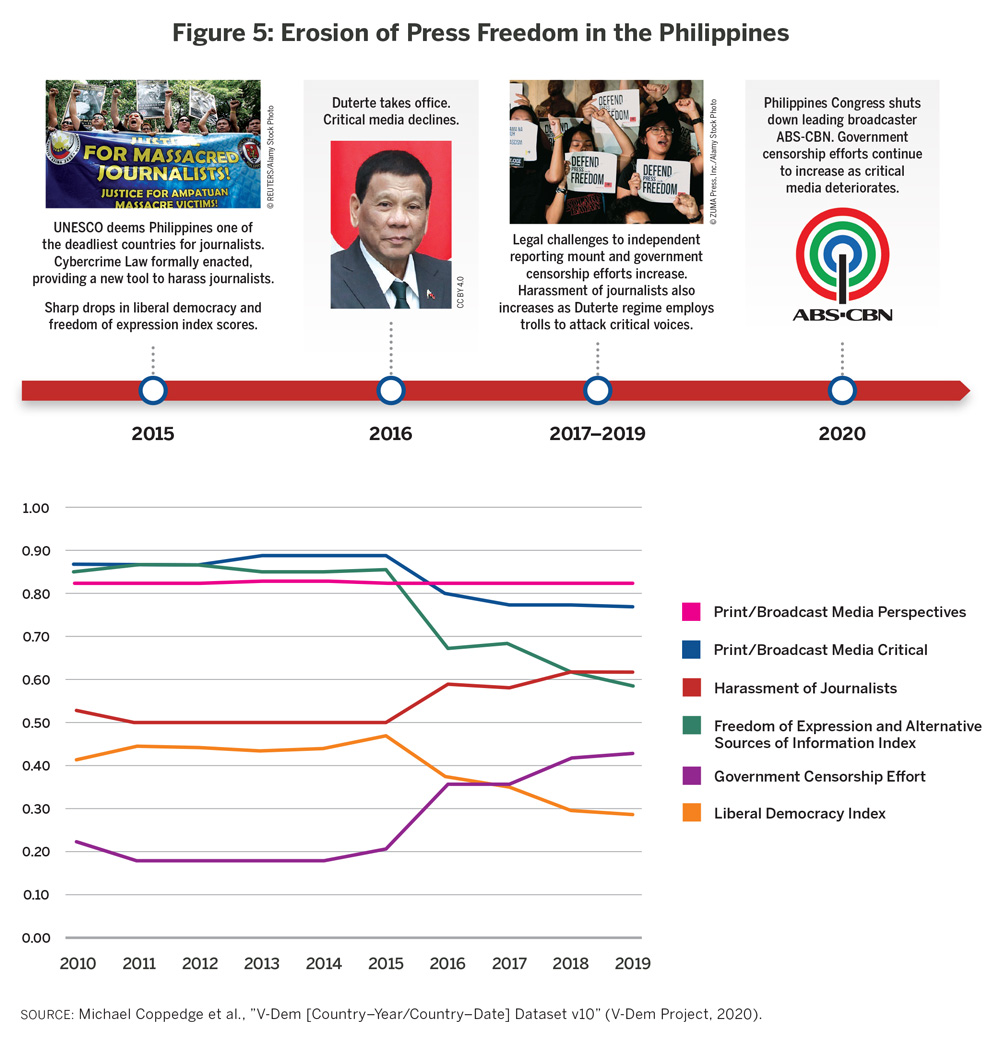

For instance, the case of Maria Ressa, founder and CEO of Rappler, has brought global attention to press freedom violations in the Philippines over the past few years. Yet, the libel law used to convict her in June 2020 has been on the books since 2012.41 Even though a dissenting Supreme Court justice warned of its possible implications for free speech, the Cybercrime Law was ruled constitutional in 2014 and formally enacted in 2015.42 The deterioration of the media environment in the Philippines, then, predates Rodrigo Duterte’s 2016 rise to power, but it was under his government that the law would be readily put to use.

Duterte’s attacks on independent media are visible in the slow deterioration of democratic indicators since 2016. This includes a dramatic increase in direct government censorship of media and harassment of journalists. A close analysis of V-Dem scores in those years, however, also emphasizes how easy it is to overlook that shrinking space. Traditional and online outlets fought to maintain their independence and continued to be publicly critical of the Duterte government’s harsh policies, so indicators like media perspectives and critical media remained strong, even as government censorship and harassment worsened. This is a marked difference from the buyouts and gradual capture of outlets in Russia, Turkey, and Hungary. Instead, Duterte applied the strongman tactics that gained him notoriety in the bloody drug war43 to attack the media with blunt force.

Maria Ressa’s case has received significant international attention, but the call to action may have come too late. Accusations of libel, tax evasion, and terrorism have threatened independent voices in the Philippines for several years, alongside online trolls that harass and “red-tag” those who disagree with the Duterte government.44 These trends are a harbinger of a grim future. They show that attacks on independent journalism are not limited to statements from Duterte45 or the prosecution of one prominent journalist. Rather, they demonstrate the vast potential for growing limitations on independent media over the next several years.

V-Dem’s 2021 dataset shows that this is already happening, as media coverage critical of the government declined over the past year. The closing space for independent media in the Philippines, including the 2020 shutdown of ABS-CBN,46 alongside wider global declines in press freedom, should serve as a warning that further destruction is likely around the corner.

Insight 3: The Learning Effect and the Autocrat's Digital Toolbox

There is no one path for would-be autocrats seeking to control their media environments. They can, however, learn from tactics used by their more effective peers. Democratization can sometimes occur through a “snowball” effect, as countries facing similar issues look to one another for solidarity and inspiration.47 Autocratization can often function in the same way. By looking to successful examples, autocratizing governments can modify and apply the tactics that best suit their specific contexts and goals.

Press freedom advocates, including Reporters Without Borders, have been struck by the extent to which leaders in Poland have mimicked tactics pioneered by their counterparts in Hungary.48 In fact, as early as 2011—four years before the PiS came to power in Poland—party leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski said, “The day will come when we will succeed, and we will have Budapest in Warsaw.”49 One report by the Brookings Institution, The Anatomy of Illiberal States, described this as “illiberal sequencing,” in which “like-minded illiberal governments assess each other’s moves to consolidate control.” The report specifically mentions how the PiS in Poland followed a similar path as Fidesz in Hungary in transforming its independent media system into a platform for government propaganda.50

Observers have dubbed these shared tactics a dictator’s playbook or toolkit.51 These tools run the gamut from restricting judicial oversight and limiting political opposition to silencing voices in civil society and the media and co-opting a national story. Many experts have honed in on digital authoritarianism, including using technology-driven methods to repress the space for free expression, such as surveillance and monitoring technology, national firewalls, and targeted content blocking.52 Given that the internet is not bound by national borders, it is not surprising that this learning effect in the media sector is most evident in efforts to control online information flows and restrict democratic use of internet platforms.

Observers have dubbed these shared tactics a dictator’s playbook or toolkit.51 These tools run the gamut from restricting judicial oversight and limiting political opposition to silencing voices in civil society and the media and co-opting a national story. Many experts have honed in on digital authoritarianism, including using technology-driven methods to repress the space for free expression, such as surveillance and monitoring technology, national firewalls, and targeted content blocking.52 Given that the internet is not bound by national borders, it is not surprising that this learning effect in the media sector is most evident in efforts to control online information flows and restrict democratic use of internet platforms.

Autocrats have long had clear tactics to choose from in controlling broadcast and print media, and have, in the past decade or so, ramped up efforts to do the same with online media. Media capture, censorship, and escalating harassment of journalists effectively allowed autocrats to control the flow of information within their borders for decades.

The internet brought new opportunities for journalists. In many closed political contexts, independent media outlets took advantage of this new, relatively unrestricted online environment to provide critical coverage of their governments.53 Social media opened the doors to citizen journalism and rapid, cross-border information sharing. All of this posed a threat to autocrats’ control of the information space.

Not only did autocratic leaders take steps to muzzle independent reporting online, they also took advantage of the same tools journalists and regular citizens use to share information and used them to promote their own narratives. But first, autocrats passed new laws aimed squarely at restricting freedom of expression online, invested in digital surveillance tools, expanded their capabilities to block websites and censor online content, and employed bots and trolls to flood social media with disinformation. In the data analysis, this is most evident in several indicators that measure the online information space, including website blocking, or “filtering”; internet censorship; social media censorship; and government dissemination of false information online.54

Not only did autocratic leaders take steps to muzzle independent reporting online, they also took advantage of the same tools journalists and regular citizens use to share information and used them to promote their own narratives. But first, autocrats passed new laws aimed squarely at restricting freedom of expression online, invested in digital surveillance tools, expanded their capabilities to block websites and censor online content, and employed bots and trolls to flood social media with disinformation. In the data analysis, this is most evident in several indicators that measure the online information space, including website blocking, or “filtering”; internet censorship; social media censorship; and government dissemination of false information online.54

In examining the data, it is also important to consider the impact of the floor effect. Press freedom indicators in Russia and China—the foremost examples of digital authoritarianism—have been consistently low for decades. This makes potentially high-impact changes in their tactics seem more or less status quo. Similarly, a close analysis of these digital tactics must account for how they fit into the wider media environment and other methods of censorship. While a government may have built significant capacity for online censorship, it may continue using more traditional means of restricting press freedoms, such as “fake news” fines, libel claims, and “economic censorship.”55

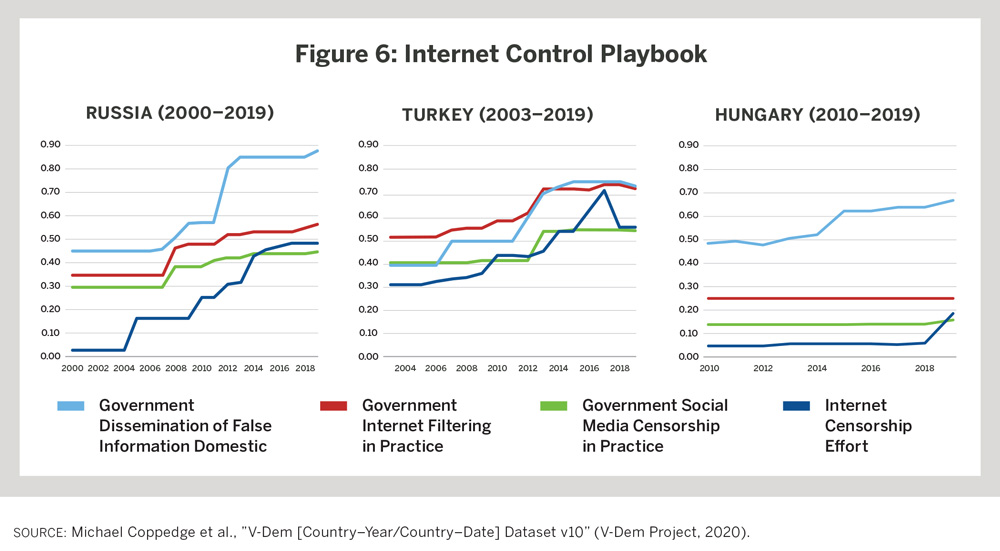

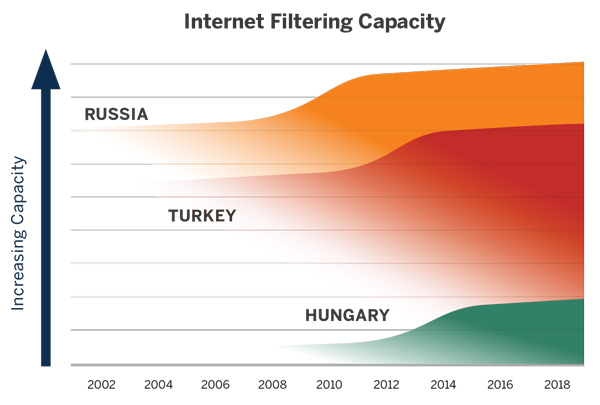

With those caveats in mind, the data analysis for this study examined trends in online censorship across 16 countries (see Appendix 2), ultimately honing in on those that appeared to follow a clear pattern. This was most evident in efforts to control online information systems in Russia, Turkey, and Hungary. These countries display clear tendencies toward digital authoritarianism and are broadly comparable in level of technological sophistication and internet penetration. For the purposes of comparison, the analysis covers periods of no real transition of government in each of the three cases (Russia since 2000, Turkey since 2003, and Hungary since 2010). This makes it all the more likely that a dramatic increase in their ability and tendency to control the online space reflects the process of autocratic peer learning.

Over the past 10 to 15 years, each country employed similar tactics to stifle freedom of expression online, though each began pursuing its agenda on a different timeline. Russia was the first to build its capacity to restrict the free flow of information online, followed by Turkey, then Hungary. The data suggest that all three countries are pulling from the same toolbox, tailoring their methods based on their needs. The timing suggests they may be taking cues from one another, learning to strengthen their grip on power by observing the techniques of other illiberal actors. The dataset, however, makes a crucial distinction between government capacity for online censorship and filtering and the level of censorship in practice. As with any toolbox, it is then the user’s choice to apply the tools in ways that make sense within their own contexts.

The common assumption holds that autocratizing countries often follow a playbook to silence independent media first devised by Russia. As illiberal governments move away from overt coercion, more indirect forms of control are becoming the norm.56 When former KGB officer Vladimir Putin took office in 2000, he was already familiar with the importance of controlling the public narrative. He pioneered many of the more covert tactics required to accomplish it, including widely disseminating government-sponsored disinformation, and attacking independent media through legal and financial means, such as regulatory restrictions and financial pressures that encourage self-censorship.57

An analysis of the data confirms that, of the three, Russia is a clear leader in its capacity to censor political information online by internet filtering—blocking access to specific websites and content considered objectionable. Russia’s internet filtering capacity increased in 2009, followed by similar increases in Turkey in 2011 and in Hungary in 2013. Russia also leads the field in its use of government dissemination of false information online, but Turkey moved rapidly to catch up, first in 2006 and more dramatically so in 2011 and 2012. Similarly, Russia increased its use of social media censorship from 2007 onward, a tactic that Turkey increasingly used only after 2012, likely reflecting the building pressure to silence dissident voices that precipitated the Gezi Park protests.

Once the Turkish government began to censor social media in earnest, it surpassed Russia’s use of the tactic. Turkey also drastically increased its use of internet filtering, first in 2006 and again in 2012. While Turkey’s capacity for this tactic increased only after Russia’s, Turkey ultimately made far greater use of this tool.

In this way, the data reflect previous findings on patterns of digital authoritarianism: “Russia relies less on filtering information and more on a repressive legal regime and intimidation of key companies and civil society.”58 While the Russian government clearly has the capacity to make use of any of these tactics, its broader environment of repression and intimidation makes internet filtering a lower priority. As Alina Polyakova, president and CEO of the Center for European Policy Analysis, and Chris Meserole, director of research for the Brookings Institution’s Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative, note in their report on digital authoritarianism, Russia’s broader method of repression is also more transferable for would-be autocrats who do not yet have Turkey’s level of technical capacity.59

The Hungarian case also reflects how autocrats make use of the menu of options provided by their peers and implement tactics that are best suited to their context. While Orbán followed Putin’s model in increasing internet filtering capacity and social media censorship, he has been cautious about widespread use of either of these techniques. Instead, Hungary’s digital tactics have focused more on increasing government dissemination of false information, closely tracking with similar increases in Russia and Turkey. Media restrictions in Hungary, as in Russia, are more often the product of outlet takeovers, direct or indirect state control, and intimidation. The apparent aversion to direct censorship and filtering also reflects the democratic image that Hungary has sought to maintain.

These three cases offer a snapshot of how peer learning may be at work among governments aiming to silence independent media. The data echo the learning effect that experts have begun to observe with concern.60 But, there are caveats. The “dictators’ playbook” for attacking the media in the 21st century is less a step-by-step guide and more a toolbox, where autocrats can choose the tactics that make the most sense at a particular moment. How and to what extent governments make use of digital tools to suppress independent journalism varies, often depending on their digital capacity. Despite this, there are clear templates that illiberal governments are increasingly borrowing and adapting from their peers. The pace of such peer learning is likely to accelerate in the future as autocrats develop new and more sophisticated techniques for employing digital techniques to subvert independent media.61

Conclusion

Understanding how the media environment is undermined as part of a country’s democratic decline provides invaluable information for those working to protect independent media, including local advocates and international assistance actors.

In discussions of both democratization and autocratization, the media sector is often siloed as a unit of analysis separate from other democratic institutions and traits. However, changes to media systems do not occur in a vacuum. They influence and are influenced by social, cultural, and political environments. Seemingly small attacks on independent media can be harbingers of larger, more repressive trends to come. Analyzing the health of the media sector can provide an early warning signal of broader democratic declines, which allows civil society and the international community to take notice and act.

Measuring and analyzing media systems to any extent, let alone in detail, remains an obstacle in the field of media development. Even some of the most robust and systematic initiatives for tracking press freedom indicators, such as those of Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders, struggle to maintain financial support. Newer initiatives similarly face challenges to expand without substantial human and financial resources, limiting their coverage to larger and more accessible media environments such as those in Europe and North America. In short, the sector faces an ongoing lack of primary and systematic data collection, limited resources to gather and understand those data, and even fewer opportunities to pair them with indicators from other relevant sectors such as good governance.

Measuring and analyzing media systems to any extent, let alone in detail, remains an obstacle in the field of media development. Even some of the most robust and systematic initiatives for tracking press freedom indicators, such as those of Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders, struggle to maintain financial support. Newer initiatives similarly face challenges to expand without substantial human and financial resources, limiting their coverage to larger and more accessible media environments such as those in Europe and North America. In short, the sector faces an ongoing lack of primary and systematic data collection, limited resources to gather and understand those data, and even fewer opportunities to pair them with indicators from other relevant sectors such as good governance.

Close attention to the media sector is integral not just in signaling the rise of autocracy, but also in defending democracies under threat. Trustworthy and independent media play the crucial role of clarifying and contextualizing the illiberal threat, countering polarization through balanced reporting, and exposing disinformation through fact‑checking.62 Thus, when the space for independent media declines, society loses an independent watchdog, space for civic action is increasingly restricted, and, ultimately, the autocratizing government is free to control the public debate and set its own agenda. This trend has already played out in Russia, Turkey, and Hungary, and threatens to worsen there and elsewhere—from Poland to the Philippines.

Appendix 1: Examined Indices and Indicators and Their Definitions

■ Liberal Democracy Index: The liberal principle of democracy emphasizes the importance of protecting individual and minority rights against the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority. The liberal model takes a “negative” view of political power insofar as it judges the quality of democracy by the limits placed on government. This is achieved by constitutionally protected civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances that, together, limit the exercise of executive power. To make this a measure of liberal democracy, the index also takes the level of electoral democracy into account.

■ Freedom of Expression and Alternative Sources of Information Index: To what extent does government respect press and media freedom, the freedom of ordinary people to discuss political matters at home and in the public sphere, as well as the freedom of academic and cultural expression?

■ Election Free and Fair: Taking all aspects of the pre-election period, election day, and the post-election process into account, would you consider this national election to be free and fair?

■ Government Censorship Effort — Media: Does the government directly or indirectly attempt to censor the print or broadcast media? Indirect forms of censorship might include politically motivated awarding of broadcast frequencies, withdrawal of financial support, influence over printing facilities and distribution networks, selected distribution of advertising, onerous registration requirements, prohibitive tariffs, and bribery.

■ Government Dissemination of False Information, Domestic: How often do the government and its agents use social media to disseminate misleading viewpoints or false information to influence their own population?

■ Government Internet Filtering Capacity: Independent of whether it actually does so in practice, does the government have the technical capacity to censor information (text, audio, images, or video) on the internet by filtering (blocking access to certain websites) if it decided to do so?

■ Government Internet Filtering in Practice: How frequently does the government censor political information (text, audio, images, or video) on the internet by filtering (blocking access to certain websites)?

■ Government Social Media Censorship in Practice: To what degree does the government censor political content (i.e., deleting or filtering specific posts for political reasons) on social media in practice?

■ Harassment of Journalists: Are individual journalists harassed—i.e., threatened with libel, arrested, imprisoned, beaten, or killed—by governmental or powerful nongovernmental actors while engaged in legitimate journalistic activities?

■ Internet Censorship Effort: Does the government attempt to censor information (text, audio, or visuals) on the internet? Censorship attempts include internet filtering (blocking access to certain websites or browsers), denial-of-service attacks, and partial or total internet shutdowns.

■ Media Corrupt: Do journalists, publishers, or broadcasters accept payments in exchange for altering news coverage?

■ Media Self-Censorship: Is there self-censorship among journalists when reporting on issues that the government considers politically sensitive?

■ Online Media Perspectives: Do the major domestic online media outlets represent a wide range of political perspectives?

■ Print/Broadcast Media Critical: Of the major print and broadcast outlets, how many routinely criticize the government?

■ Print/Broadcast Media Perspectives: Do the major print and broadcast media represent a wide range of political perspectives?

Appendix 2: Countries Analyzed

■ Benin

■ Bolivia

■ Brazil

■ Egypt

■ Hungary

■ India

■ Nicaragua

■ Nigeria

■ Philippines

■ Poland

■ Russia

■ Serbia

■ Thailand

■ Tunisia

■ Turkey

■ Ukraine

Acknowledgements

Luis García Espinal provided quantitative analysis support to this report.

Cover Photo Credit: © Majority World CIC/Alamy Stock Photo

Footnotes

- Tom Gerald Daly, “Democratic Decay: Conceptualising an Emerging Research Field,” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 11 (2019): 9–36, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40803-019-00086-2.

- “Global Media Defense Fund,” UNESCO, accessed October 11, 2021, https://en.unesco.org/global-media-defence-fund.

- A New Deal for Journalism (Forum on Information & Democracy, 2021), https://informationdemocracy.org/working-groups/sustainability-of-journalism/.

- Rachel M. Gisselquist, Miguel Niño-Zarazúa, and Melissa Samarin, Does aid support democracy? A systematic review of the literature (United Nations University, 2021), http://dx.doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2021/948-8.

- “The Gezi Park Protests: The Impact on Freedom of Expression in Turkey,” PEN International, March 14, 2014, https://pen-international.org/news/turkey-end-human-rights-violations-against-writers-and-journalists; Namo Abdulla and Ezel Sahinkaya, “Under Siege: How Failed Coup Gave Way to Major Media Crackdown in Turkey,” Voice of America, July 15, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/press-freedom/under-siege-how-failed-coup-gave-way-major-media-crackdown-turkey.

- Nazifa Alizada et al., Autocratization Turns Viral: Democracy Report 2021 (Gothenburg, Sweden: University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute, 2021), https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/74/8c/748c68ad-f224-4cd7-87f9-8794add5c60f/dr_2021_updated.pdf.

- Ibid.

- It is important to note that while media development experts and practitioners may understand empirically that there is a potential causal relationship among indicators, these explanatory frameworks and the methodology used for analyzing data are solely descriptive. For this reason, trends identified do not enable any assessment of correlation or causality.

- Masha Gessen, The Man without a Face (New York: Riverhead Books, 2012), 174.

- Celestine Bohlen, “Putin Defends Police Raid on Media Company,” New York Times, May 13, 2000, https://www.nytimes.com/2000/05/13/world/putin-defends-police-raid-on-media-company.html.

- “Attacks on the Press 2001: Russia,” Committee to Protect Journalists, March 26, 2002, https://cpj.org/2002/03/attacks-on-the-press-2001-russia/.

- Anna Lührmann et al., Democracy at Dusk? Democracy Report 2017 (Gothenburg, Sweden: University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute, 2017), https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/b0/79/b079aa5a-eb3b-4e27-abdb-604b11ecd3db/v-dem_annualreport2017_v2.pdf, 21.

- Mehmet Yavuz, “Western Linkage vs. Illiberalism: De-democratization in Hungary and Turkey,” Central European University, 2019, http://www.etd.ceu.edu/2019/yavuz_mehmet.pdf.

- Committee to Protect Journalists, “Turkey’s Press Freedom Crisis,” October 2010, https://cpj.org/reports/2012/10/turkeys-press-freedom-crisis-appendix-i-journalists-in-prison/; Committee to Protect Journalists, “Turkey’s Crackdown Propels Number of Journalists in Jail Worldwide to Record High,” December 13, 2016, https://cpj.org/reports/2016/12/journalists-jailed-record-high-turkey-crackdown/.

- “Turkey—world’s biggest prison for journalists,” Committee to Protect Journalists, last updated September 27, 2016, https://rsf.org/en/news/turkey-worlds-biggest-prison-journalists; Committee to Protect Journalists, “Hundreds of journalists jailed globally becomes the new normal,” December 13, 2018, https://cpj.org/reports/2018/12/journalists-jailed-imprisoned-turkey-china-egypt-saudi-arabia/.

- Perceptions towards Freedom of Expression in Turkey (Washington, DC: Freedom House, March 2020), https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/Perceptions%20towards%20Freedom%20of%20Expression%20in%20Turkey%202020%20%281%29.pdf.

- “Center-Right Fidesz Party Sweeps to Victory in Hungary,” CNN, April 26, 2010, http://www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/europe/04/26/hungary.election.results/index.html.

- “New Report: Hungary Dismantles Media Freedom and Pluralism,” International Press Institute, December 3, 2019, https://ipi.media/new-report-hungary-dismantles-media-freedom-and-pluralism/.

- Stefan Bos, “Hungary Introduces Europe’s Most Restrictive Media Law,” Voice of America, December 30, 2010, https://www.voanews.com/a/hungarian-president-signs-controversial-media-law-112693124/170413.html.

- Marton Dunai, “How Hungary’s Government Shaped Public Media to Its Mould,” Reuters, February 19, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hungary-media-insight/how-hungarys-government-shaped-public-media-to-its-mould-idUSBREA1I08C20140219.

- Judy Dempsey, “Hungary Waves Off Criticism over Media Law,” New York Times, December 25, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/26/world/europe/26hungary.html.

- Anna Lührmann et al., Autocratization Surges – Resistance Grows: Democracy Report 2020 (Gothenburg, Sweden: University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute, 2020), https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/de/39/de39af54-0bc5-4421-89ae-fb20dcc53dba/democracy_report.pdf; Zselyke Csaky, Dropping the Democratic Facade (Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2020), https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2020/dropping-democratic-facade.

- Sevanti Ninan, “How India’s News Media Have Changed since 2014: Greater Self-Censorship, Dogged Digital Resistance,” Scroll.in, July 5, 2019, https://scroll.in/article/929461/greater-self-censorship-dogged-digital-resistance-how-indias-news-media-have-changed-since-2014.

- Mahima Kaul, “India’s Modi Bypasses Mainstream Media and Takes to Twitter,” Index on Censorship, August 27, 2014, https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2014/08/india-modi-mainstream-media-press/; Gopal Sathe, “How the BJP Automated Political Propaganda on WhatsApp,” Huffington Post, April 16, 2019, https://www.huffpost.com/archive/in/entry/bjp-automated-political-propaganda-whatsapp-sarv_in_5cb62076e4b082aab08d7f18.

- New York Times Editorial Board, “India’s Government Censorship,” New York Times, August 17, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/18/opinion/indias-government-censorship.html.

- Kate Musgrave, “India’s Other Media Boom,” Center for International Media Assistance (blog), April 16, 2019, https://www.cima.ned.org/blog/indias-other-media-boom/.

- Nehal Johri, “India’s Internet Shutdowns Function like ‘Invisibility cloaks,’” Deutsche Welle, November 13, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/indias-internet-shutdowns-function-like-invisibility-cloaks/a-55572554.

- Alizada et al., Autocratization Turns Viral.

- “Freedom in the World 2021 – India,” Freedom House, 2021, https://freedomhouse.org/country/india/freedom-world/2021; Vindu Goel and Jeffrey Gettleman, “Under Modi, India’s Press Is Not So Free Anymore,” New York Times, April 2, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/02/world/asia/modi-india-press-media.html.

- Christian Davies, “Hostile Takeover: How Law and Justice Captured Poland’s Courts,” Freedom House, 2018, https://freedomhouse.org/report/analytical-brief/2018/hostile-takeover-how-law-and-justice-captured-polands-courts.

- “MFRR Report: Erosion of Media Freedom Gathers Pace in Poland,” International Press Institute, February 11, 2021, https://ipi.media/mfrr-report-erosion-of-media-freedom-gathers-pace-in-poland/.

- Kate Musgrave, “A Decade of Closing Space in Hungary: Joint Report Highlights a Captured Media Environment,” Center for International Media Assistance (blog), January 9, 2020, https://www.cima.ned.org/blog/a-decade-of-closing-space-in-hungary-joint-report-highlights-a-captured-media-environment/.

- Mark Nelson, “State Takeover of Public Media in Poland: Is an Illiberal Axis Emerging within the EU’S Walls?” Center for International Media Assistance (blog), January 11, 2016, https://www.cima.ned.org/blog/public-media-in-poland-illiberal-axis/.

- “Polish Authorities Stepping Up Harassment of Independent Media,” Reporters Without Borders, December 7, 2018, https://rsf.org/en/news/polish-authorities-stepping-harassment-independent-media; “Poland: Record Fine for Polish TV News Channel,” Reporters Without Borders, December 12, 2017, https://rsf.org/en/news/poland-record-fine-polish-tv-news-channel.

- “European Union Must Act on Media Freedom in Poland, Hungary and Slovenia,” International Press Institute, March 9, 2021, https://ipi.media/european-union-must-act-on-media-freedom-in-poland-hungary-and-slovenia/.

- Gessen, The Man without a Face.

- Andrew MacDowall and Bibi van der Zee, “‘Local Media Are Simply Disappearing’: How Financial Pressures Are Killing Independent Media,” Guardian, November 29, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2017/nov/30/closure-of-nepszabadsag-hungarian-daily-highlights-threat-to-independent-media.

- Marius Dragomir, “Central and Eastern Europe’s Captured Media,” Project Syndicate, May 6, 2019, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/press-freedom-hungary-central-eastern-europe-by-marius-dragomir-2019-05.

- Andrew Finkel, Captured News Media: The Case of Turkey (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2015), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/captured-news-media-turkey/.

- “VPN News,” Diken, https://www.diken.com.tr/kategori/vpn-haber/.

- Jason Gutierrez and Alexandra Stevenson, “Maria Ressa, Crusading Journalist, Is Convicted in Philippines Libel Case,” New York Times, June 14, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/14/business/maria-ressa-verdict-philippines-rappler.html.

- Lian Buan, “Aquino’s Contested Cyber Libel Law Gets New Claws in Ruling vs Rappler,” Rappler, June 16, 2020, https://www.rappler.com/nation/aquino-contested-cyber-libel-law-gets-new-claws-ruling.

- “Philippines’ Duterte Hails Drug War but Says ‘Long Way’ to Go,” France24, July 26, 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20210726-philippines-duterte-hails-drug-war-but-says-long-way-to-go.

- Oliver Haynes, “Deadly ‘Red-Tagging’ Campaign Ramps Up in Philippines,” Voice of America, February 18, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/east-asia-pacific/deadly-red-tagging-campaign-ramps-philippines.

- “RSF Condemns Philippine President-Elect’s Comments about Journalists,” Reporters Without Borders, June 1, 2016, https://rsf.org/en/news/rsf-condemns-philippine-president-elects-comments-about-journalists.

- Jason Gutierrez, “Philippine Congress Officially Shuts Down Leading Broadcaster,” New York Times, July 10, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/10/world/asia/philippines-congress-media-duterte-abs-cbn.html.

- Samuel Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991).

- “Poland about to Censor Privately-Owned Media, like Its Hungarian Ally,” Reporters Without Borders, July 31, 2020, https://rsf.org/en/news/poland-about-censor-privately-owned-media-its-hungarian-ally.

- Neil Buckley and Henry Foy, “Poland’s New Government Finds a Model in Orban’s Hungary,” Financial Times, January 6, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/0a3c7d44-b48e-11e5-8358-9a82b43f6b2f.

- Alina Polyakova et al., The Anatomy of Illiberal States: Assessing and Responding to Democratic Decline in Turkey and Central Europe (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/illiberal-states-web.pdf (second quote from page 6).

- DemDigest, “Dictator’s Playbook Is Karimov’s Legacy,” Democracy Digest, September 2, 2016, https://www.demdigest.org/dictators-playbook-karimovs-legacy/; Richard Fontaine and Kara Frederick, “The Autocrat’s New Tool Kit,” Wall Street Journal, March 15, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-autocrats-new-tool-kit-11552662637.

- Alina Polyakova and Chris Meserole, Exporting Digital Authoritarianism (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FP_20190826_digital_authoritarianism_polyakova_meserole.pdf.

- Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson, eds., Digital Media Mapping: Global Findings (New York: Open Society Foundations, July 2014), https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/mapping-digital-media-global-findings.

- V-Dem’s indicator on government dissemination of false information refers only to the spread of false information on social media platforms—a specification that does not begin to address other mechanisms for disseminating false information and propaganda, including media capture and manipulation of state-owned media.

- The Role of Media in Democracy: A Strategic Approach (Washington, DC: US Agency for International Development, Center for Democracy and Governance, June 1999), https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2496/200sbc.pdf, 22.

- Tom Paskhalis, Bryn Rosenfeld, and Katerina Tertytchnaya, “The Kremlin Has a New Toolkit for Shutting Down Independent News Media,” Washington Post, June 29, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/06/29/kremlin-has-new-toolkit-shutting-down-independent-news-media/.

- Laura Rosenberger and Jamie Fly, “Shredding the Putin Playbook,” Democracy Journal, 2018, https://democracyjournal.org/magazine/47/shredding-the-putin-playbook/; Ann Cooper, “Conveying Truth: Independent Media in Putin’s Russia,” Harvard University Kennedy School, Shorenstein Center, August 10, 2020, https://shorensteincenter.org/independent-media-in-putins-russia/.

- Polyakova and Meserole, Exporting Digital Authoritarianism, 1.

- Ibid.

- Polyakova et al., The Anatomy of Illiberal States.

- Seva Gunitsky, “Corrupting the Cyber-Commons: Social Media as a Tool of Autocratic Stability,” Perspectives on Politics 13, no. 1 (March 2015): 42–54, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714003120.

- Anna Lührmann et al., eds., Defending Democracy against Illiberal Challengers: A Resource Guide (Gothenburg, Sweden: University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute, 2020), https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/f3/f0/f3f09467-bcf7-4f8a-9ad9-e83171673705/v-dem_resourceguide_20-05-28_final-better.pdf.