Internet Freedom Rates Show Negative Convergence Worldwide

Guest post by Christopher Walker and Robert W. Orttung.

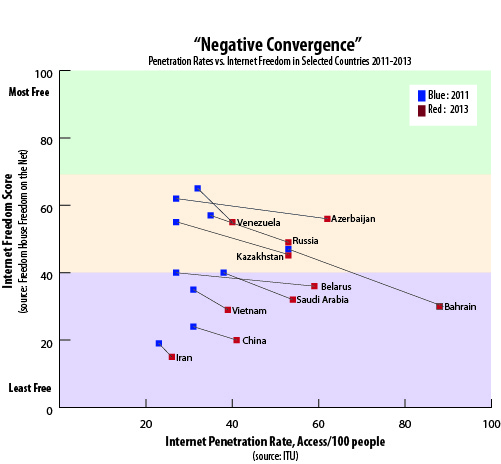

Not all that long ago, it was widely assumed that the Internet would set off geysers of information everywhere, with political change sure to follow. Instead, it looks as if methods for bringing to heel political expression on traditional media in authoritarian settings are being adapted and applied to new media with increasing effect. The trend of “negative convergence,” in which the space for meaningful political expression online shrinks and moves in the direction of less free traditional media, has profoundly troubling implications.

The Internet’s spread has been remarkable, and many authoritarian systems are part of the trend–indeed, their governments have little choice in the matter unless they want to try ruling the next North Korea. Economic growth and development require being “wired.” Thus in fast-growing but authoritarian Vietnam, 40 percent of the populace has Internet access. In Kazakhstan and Saudi Arabia that figure is even higher at approximately 55 percent. In Bahrain, it is nearly 90 percent. China is at 45 percent Internet penetration and now has nearly 600 million Internet users and more than 300 million microbloggers, most of them on Sina Weibo, China’s version of Twitter. In Russia, which recently passed the 50 percent mark, web-based media such as TV Rain are helping the opposition to reach larger audiences.

Critically, even as countries such as Vietnam, Azerbaijan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and other Gulf States see fast growth in Internet access, Freedom House rates them as becoming less free online. Such rankings indicate that in these settings a “negative convergence” may be taking place in which the news content of new media is being subjected to enhanced control as old media long have been.

The Freedom on the Net scores by Freedom House have been inverted from their traditional 0-100 scale, where 0 is most free and 100 is least free. In this image, 0 is least free, and 100 is most free.

As the Internet looms larger, so does authoritarian political interference with it. In this light, Russia’s 2012 law allowing the government to shut down sites with inappropriate content—as well as a decree developed by the Communications Ministry and the FSB (the KGB’s successor) and slated to take effect later in 2014 that will require Internet service providers to monitor all Internet traffic, including IP addresses, telephone numbers, and usernames–mark a clear step backward in terms of Internet freedom. On 1 September 2013, Vietnam put into effect Decree 72, an ambitious measure that looks to ban online users in the country from discussing current events and sharing news articles. China’s government, meanwhile, sets the pace when it comes to online censorship and has also become a leading developer of sophisticated methods for suppressing political communication online.

Like television, the Internet is something that authoritarian rulers realize that they must try to control. The freewheeling world of online communications and discourse is increasingly worrying them. In order to get a handle on it, regimes in China, Russia, Iran, and elsewhere are turning to approaches that have proven useful in the “management” of traditional media.

Yet the task is not the same: Exerting control over key political content of a central television network is a lot easier than reining in such information online. But authoritarian regimes are displaying great determination and an eye for innovation in achieving their objectives. As with traditional media, the restrictive measures being tested do not aim to block everything, but instead chiefly attempt to obstruct news about politics or other sensitive issues from consistently reaching key audiences. As Internet use and penetration increase in authoritarian countries, their regimes are working harder than ever to find ways of impeding the circulation of credible political information through cyberspace.

The range of restrictive measures, some overt, but others more subtle and sophisticated, that Beijing, Moscow, and their imitators have been taking should at the very least make us ask whether the Internet can withstand the authoritarian encroachment and anchor itself as an open platform for political discussion in authoritarian states.

Perhaps the balance will change–perhaps new media innovation will evade the tighter controls of authoritarian regimes and drive political conversation in a more cohesive and coherent way. But absent real political change in the meantime to enable authentic media reform, can new media keep meaningful political discourse alive?

Christopher Walker is executive director of the International Forum for Democratic Studies at the National Endowment for Democracy. Robert Orttung is assistant director of the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies at George Washington University’s Elliott School for International Affairs. This post is drawn from a longer essay that appears in the January 2014 issue of the Journal of Democracy. A panel event based on the ideas in the article will be held on January 28, 2014, at the George Washington University.

Comments (0)