The Philippines has been one of the most dangerous places outside of a war zone to be a journalist – over the past decade, 41 journalists have been killed without the assailants being brought to justice, according the Committee to Protect Journalists. Since Rodrigo Duterte became president of the Philippines in June 2016, the environment has gotten even more volatile. This past July, Duterte launched a scathing attack on media organizations that have been critical of his administration in his State of the Nation address. The rhetoric has led to increased online threats and harassment and made the work of independent journalists harder in an already precarious context.

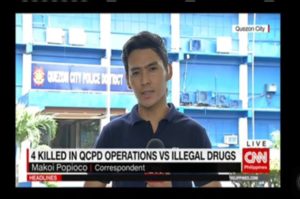

Makoi Popioco of CNN Philippines, a former National Endowment for Democracy (NED) Hurford Youth Fellow who has spent his career focusing on official corruption, mismanagement, and human rights abuses, noted in an interview that the situation has gotten worse recently as journalists in the Philippines are often targeted for performing their watchdog role.

“I think the main challenge of the media here right now is the question of delivering the news. Basically, the media here is under attack,” said Popioco. “We cannot afford to commit mistakes because then we will be under attack. If we report false information, it will be bad for us.”

Reporting truthful information is a core tenant in ethical journalism, but Popioco also says that under Duterte, if there is a story he doesn’t like (even if it’s factual), he may call it fake news, which is similar to other leaders with authoritarian tendencies.

“In the past, [Duterte] has issued a lot of conflicting statements. He has accused the media of misquoting him, saying he was joking and that he should not be taken seriously,” Popioco said. “As a country’s leader, you’re supposed to speak in concrete terms, so he accuses the media of misquoting him. The effect of that is he may boycott us and then he will just have the state television be the primary station of government affairs. He threatened to do that.”

Popioco went on to say that this practice of giving conflicting statements to the media is encouraged by Duterte to other members of his council, “Our press secretary held a press conference blaming the media for [giving the country] a bad image. And they demanded the media to portray the country as a safe place for tourists.”

Popioco also said that the overall media situation in the Philippines has problems beyond the current president. Popioco cited a 2009 massacre to show that the Philippines has struggled with protecting journalists long before Duterte came to power.

The Maguindanao massacre, in which 58 people were killed, occurred when supporters of politician Esmael Mangudadatu went to file his candidacy for governor of the state of Minadanao. Among the dead were 32 journalists who were covering Mangudadatu at the time. His candidacy posed a threat to then-governor Andal Ampatuan Jr., a member of a powerful family in Mindanao, who was planning to run for re-election. Ampatuan and his allies were considered the main suspects. The investigation and the trial of the 28 suspects has dragged on, and to date, no one has been brought to justice.

“The families are still grieving from what happened,” Popioco elaborated. “So far the perpetrators of those crimes have not been held accountable. Some group of journalists here in the Philippines lobby for protections [but] there is no landmark legislation that has been passed in the last 10 years that would protect journalists.”

The Duterte regime presents another obstacle for Filipino journalists searching for the truth with a barrage of online threats, harassment, and propaganda since he took office. Though the country’s press issues have been persistent regardless of regime, the current media environment with journalists targeted online as well as in-person makes the situation even more treacherous.

“In terms of the kind of work and the kind of things we have to employ, it’s a brilliant time to be a journalist and we have to test our ethics,” Popioco said about the future of journalism in the Philippines. “We are under attack and I think people like me are more challenged to do better and get the facts. You cannot afford to make mistakes because the second you make mistakes you are losing the one weapon you have as journalists. We have to be perfect more than ever, because we will be under attack.”

Adam Tismaneanu is a fourth-year Journalism and Media & Screen Studies major at Northeastern University where he has written for the New England Climate Review and Northeastern Journalism Abroad in Spain.

Comments (0)

Comments are closed for this post.